In today’s video we will investigate some bizarre archaeological disocveries. Watch the video below to find out more!

12 Most Incredible And Amazing Recent Discoveries

The past few years have been incredible ones when it comes to archaeology. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that most of the most incredible discoveries made in the past century have been found within the past decade. We know that’s a bold statement, so we’re going to show you the proof in this video. It’s full of astonishing recent archaeological finds!

15 Places Women are not Allowed to Visit

In the following video we will be exploring 15 places around the world, which women are not allowed to visit. Enjoy!

Most Bizarre Discoveries Made In The Ice | Compilation

Today’s video will be a compilation of the most bizarre discoveries made in the ice. Watch the video below to find out more!

10 Crossbreeding Experiments from the Dark Past!

To what extent may man intervene in the course of nature? Where does the line blur between a useful crossbreed and the creation of a Frankenstein monster? Today we're going to take a look at some unique hybrid experiments with you that are leaving us with our jaws on the floor! Especially the 9th point of our video will leave you absolutely stunned! Given the terrifying creatures already being bred in the scientists' labs, we'd prefer a cross between a thumbs up and a subscription from you! And be sure to leave us a comment below and let us know which of these strange hybrids you find the most interesting!

Caral: The Pyramid City In Peru That Predates Egypt’s Oldest Pyramid And The Incas By 4,000 Years

Colossal pyramid structures in the Americas as old as those in Egypt? The Sacred City of Caral-Supe, in central coastal Peru, boasts an impressive complex of ancient monumental architecture constructed around 2600 B.C., roughly the same time as the earliest Egyptian pyramid. Archaeologists consider Caral one of the largest and most complex urban centers built by the oldest known civilization in the Western Hemisphere.

The 1,500-acre site, situated 125 miles north of Lima and 14 miles from the Pacific coast, features six ancient pyramids, sunken circular plazas and giant staircases, all sitting on a windswept desert terrace overlooking the green floodplains of the winding Supe River. Its largest pyramid, also known as Pirámide Mayor, stands nearly 100 feet tall, with a base that covers an area spanning roughly four football fields. Radiocarbon dating on organic matter throughout the site has revealed it to be roughly between 4,000 to 5,000 years old, making its architecture as old—if not older—than the Step Pyramid of Saqqara, the oldest known pyramid in ancient Egypt.

That remarkable discovery places Caral as one of the oldest known cities in the Western Hemisphere. Coastal Peru has long been considered one of the six recognized cradles of world civilization, and new archaeological discoveries continue to push back the dates of when the region’s “mother culture” was established. Caral was the first extensively excavated site among some two dozen in a zone along Peru’s central coast known as the Norte Chico area. Archaeologists believe the sites collectively represent the oldest center of civilization in the Americas, one which lasted from roughly 3000 to 1800 B.C., completely uninfluenced by outside forces. It flourished nearly 4,000 years before the start of the powerful Incan Empire.

Its Age Wasn’t Initially Clear to Scientists

Despite Caral’s significance, decades passed between when the first scholars stumbled upon the area, and when they recognized its importance. German archaeologist Max Uhle explored the Supe Valley, but not Caral itself, as part of a wide-ranging study of ancient Peruvian cities in the early 1900s. But it was American historian Paul Kosok, who is largely recognized as the first scholar to recognize and visit what is now known as the site of Caral in 1948. In his 1965 book, Life, Land and Water in Ancient Peru, he referred to the site as Chupa Cigarro Grande, after a nearby hacienda.

The sheer size and complexity of the site, however, led many to believe Caral’s structures were made only more recently, largely leaving it to go ignored. It was only in 1994, when Peruvian archaeologist Ruth Shady of National University of San Marcos started studying the site, that she realized, in the absence of finding any ceramics, that Caral might date before the advent of pot-firing technology.

But Shady needed to substantiate her claims. While excavating the largest pyramid, she and her team found the remains of reed-woven bags, known as shicras, filled with large stones to support the pyramid’s retaining walls. In 1999, she sent the reed samples for radiocarbon dating to veteran archaeologists Jonathan Haas, at Chicago’s Field Museum, and Winifred Creamer, at Northern Illinois University.

The results, published in the journal Science in April 2001, were monumental. Caral, along with other ancient Norte Chico sites in the Supe Valley were “the locus of some of the earliest population concentrations and corporate architecture in South America,” they wrote. At that time, Caral was hailed as the oldest known city in the hemisphere; since then, other Norte Chico sites, dating several hundred years earlier, have been unearthed—and discoveries continue.

The Massive Complex Signals an Advanced Society

Shady, who heads the Caral-Supe Special Archaeological Project, has continued to probe the depths of the long-lost ancient city—which, compared to some highly looted archaeological sites, had remained relatively untouched due to its late discovery. Her finds have revealed a site of epic proportions, one that not only looms large with its massive pyramids, but with other architecturally complex elements including extensive residential units, multiple plazas and an impressive sunken circular amphitheater that would have been large enough to hold hundreds of people. It was there that Shady and her team unearthed the remains of dozens of flutes made of pelican bones, relics of the importance of music to the ancient people of Caral.

Another significant find came in the Gallery Pyramid (or Pirámide de la Galería), which reaches 60 feet tall. On the twelfth step of its central stairway, archaeologists unearthed a quipu, an ancient method of recording information used through Incan times, believed to be among the oldest discovered in the Americas.

That such a highly structured society existed implied the presence of strong leadership and thousands of manual laborers. “In order to set up this city and its monumental buildings according to a coordinated design, prior planning, experts and a centralized government were necessary,” wrote Shady in “The Sacred City of Caral,” a nomination file submitted to Unesco, which inscribed the archaeological site onto the World Heritage List in 2009.

Why It Was Abandoned Remains a Mystery

The existence of such a large and well-organized inland civilization has helped smash the “maritime hypothesis,” or the long-running theory that complex Andean societies evolved first from the coast, where they were heavily reliant on fishing, and only later progressed inland. Dr. Shelia Pozorski, and her husband, Thomas, professors emeriti at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, questioned the maritime hypothesis as early as 1990. But it wasn’t until “archaeological evidence and dates for Caral and other Norte Chico sites became available, that the ‘maritime hypothesis’ was more soundly refuted,” she said. Coastal settlements and inland ones existed and developed at the same time, with Caral larger and more complex than any coastal villages that may have existed in the area before.

The discovery of cotton seeds, fibers and textiles, along with the remains of clam shells and fish bones at the site—as well as a large fishing net that was as old as Caral, found along the coast—helped Shady formulate another theory: The farmers at Caral grew and traded cotton in exchange for fish and shellfish from the villagers along the coast. The end result: production surpluses, local labor specialization and the emergence of political authorities in charge of trading. In short, Caral had a burgeoning model of social and political organization.

While much is known about Caral, perhaps there’s more that’s unknown—including why it developed in such a complex manner, and its relationship to the other ancient Norte Chico sites.

The largest mystery, however, might be why it was abandoned after being inhabited for nearly a thousand years. “There is no concrete evidence indicating that a single event, like an earthquake or large flood, ended the occupation of Caral,” Dr. Thomas Pozorski says. “It is much more likely that several factors contributed to the decline of the state, including internal strife and discord which is very difficult to prove in archaeology.”

The Ancient and Medieval African Kingdoms: A Complete Overview

The African Kingdoms goes over the BOTH the Ancient and Medieval periods of African history. It is meant to be an overview.

It begins with a general look at Africa's different natural regions, before getting into Ancient Africa (the Nubians, kingdom of Axum, the smaller cultures in North and West Africa, and the Bantu migrations), and then Medieval Africa (African religion, the coming of Islam, the Ethiopian Empire, the Swahili Coast, West African Empires, the Central and Southern kingdoms), and ending with daily life, slavery, and arts and culture.

The Rise and Fall of the Empires

In this video, we explore the fascinating history of the rise and fall of empires throughout the ages. From the ancient empires of Greece and Rome to the more recent empires of Britain and France, we delve into the reasons behind their rise to power and their eventual decline.

Through this journey, we examine the cultural, economic, and political factors that played a crucial role in the rise and fall of these empires. We also take a closer look at some of the most iconic empires in history, such as the Byzantine Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Mongol Empire, and explore their lasting legacies.

Join us on this exploration of the past as we visit some of the most significant landmarks and ruins of these empires, from the Acropolis to the Colosseum, from the Great Wall of China to the Taj Mahal.

First Look Inside the Great Pyramid Queen's Chamber Northern Shaft

The Great Pyramid of Egypt is the most well studied ancient structure in the entire world, which makes it all the more strange that for 20 years there has been important information concerning this structure that is missing from the public domain, and that’s pictures, footage and a full description of the inside of the Queen’s Chamber Northern Shaft.

It is discussed in a 2014 paper written by Dr Zahi Hawass, which is part of a publication by the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities titled 'Quest for the Dream of the Pharaohs. The paper includes a description and a few black and white photographs, but is incredibly difficult to get hold of.

This shaft is critical in just about every Great Pyramid hypothesis and even if it isn’t, it can’t go unnoticed. Any pyramid researcher who tries to explain the finer details of the Great Pyramid must explain the four so-called air shafts in a logical way, but how can any hypothesis have any merit if nobody even knows what the inside of Queen’s Chamber Northern Shaft looks like? Thankfully we can change that with this video.

A friend of the Ancient Architects channel has supplied me with 51 colour photographs taken from the Pyramid Rover robot, which explored the shaft in 2002, as well as a copy of the original mission report. With this, we can now see the shaft in its entirety and learn more about this elusive pyramid shaft. Here I'll add a disclaimer: The "Never" on the thumbnail image refers to 99.9% of viewers of this channel. Some people have obviously seen them but not many.

Most people will never have seen these pictures before, but they will be of interest to anybody researching the Great Pyramid of Egypt. Not only do we learn about the exact shape and rock type, but we also learn of a number of new anomalies, previously not discussed.

The Unspeakable Things Pope John XII Did During His Reign

“Our” pope, John XII, ruled over Western Christendom from 955-963 some six hundred years after Pope Damasus. Damasus had been appointed by the Emperor Theodosius, but by the time of John XII, popes were elected by the people of Rome. Well, that's kind of misleading, for while the people of the city did vote for the pope, the vast majority of those votes were bought by powerful families who either had a son or other family member “running” for the position. Essentially, the position of pope went to the highest bidder. What's more the candidates for the position were oftentimes not exactly “paragons of virtue.”

As a matter of fact, some of them, like John XII did not know or care much about religion at all. What many popes and their backers cared about was POWER, and in the Middle Ages, the pope was considered infallible. In other words, he could make no mistakes, at least as far as it concerned most the people. Kings and emperors were another matter, and at many times in history, the popes were tools of those who held military power. The pope, however, held the balance, for winning the pope over to your side was costly. In return for his support, rulers often had to pay bribes, give up land and at least to some degree, listen to what the pope “suggested”, for the pope had the ultimate weapon – excommunication. Being “excommunicated” meant that a person was no longer able to take part in Church rites. The practices, such as Holy Communion, confession, and attending Mass. Without these rites and practices, a person could NOT ever ascend to Heaven, and could not, at least in theory, associate with any Christian, and all of the Christians in Western Europe at the time were Catholic.

The pope had tremendous power. John XII Before he took his “papal name” of John, he was known as “Octavianus.” His father, the powerful ruler of Rome, Duke Alberic II, named him after the first Roman emperor, Octavian – also known as Augustus, for Alberic wanted his son to follow him not only as the political leader of Rome, but as pope. Alberic's family, the Tusculum clan, had ruled the area for decades. They were rich, powerful and respected, and Alberic himself was well-loved. After his death in 954, the rich and powerful in Rome made certain that Octavianus was elected pope, and the 18 year old became one of the most powerful and richest men in the world as “John XII.”

Researchers "shocked" to discover 2,000-year-old Egyptian mummy was a pregnant woman

In the early 19th century, the University of Warsaw acquired an Egyptian mummy encased in an elaborate coffin identifying the deceased as a priest named Hor-Djehuty. Nearly 200 years later, in 2016, researchers using X-ray technology were surprised to discover that the mummified remains belonged not to a man, as the inscription indicated, but to an unidentified young woman. Then came another revelation: While examining images of the mummy’s pelvic area, researchers spotted a tiny foot—a sure sign that the woman was pregnant at the time of her death, reports Monika Scislowska for the Associated Press (AP).

Writing in the Journal of Archaeological Science, the team describes the find as “the only known case of an embalmed pregnant individual.”

This mummy, the scientists hope, will shed new light on pregnancy in the ancient world.

Experts with the Warsaw Mummy Project have dubbed the deceased the “mysterious lady of the National Museum in Warsaw” in honor of the Polish cultural institution where she is now housed. They do not know who the woman was or exactly where her body was discovered. Though the individual who donated the mummy to the university claimed it came from the royal tombs at Thebes, a famed burial site of ancient pharaohs, the study notes that “in many cases antiquities were misleadingly ascribed to famous places in order to increase their value.”

When the mummy first arrived in Poland, researchers assumed it was female because its coffin was covered in colorful and luxurious ornaments. After the hieroglyphs on the coffin were translated in the 1920s, however, the body was reclassified as male based on inscriptions bearing the name of a scribe and priest, writes Lianne Kolirin for CNN. As a result, when modern researchers undertook a non-invasive study of the mummy using X-ray and CT scans, they expected to find a male body beneath the ancient wrappings.

“Our first surprise was that it has no penis, but instead it has breasts and long hair, and then we found out that it’s a pregnant woman,” co-author Marzena Ozarek-Szilke, an anthropologist and archaeologist at the University of Warsaw, tells the AP. “When we saw the little foot and then the little hand [of the fetus], we were really shocked.”

At some point, it seems, the body of a pregnant woman was placed inside the wrong coffin. Ancient Egyptians are known to have reused coffins, so the switch may have happened many centuries ago. But the study also notes that during the 19th century, illegal excavators and looters often partially unwrapped mummies and searched for valuable objects before returning the bodies to coffins—“not necessarily the same ones in which the mummy had been found.” The Warsaw mummy does indeed show signs of looting—namely, damaged wrappings around the neck, which may have once held amulets and a necklace.

Embalmers mummified the woman with care at some point in the first century B.C. She was buried alongside a rich array of jewelry and amulets, suggesting that she was of high status, lead author Wojciech Ejsmond, an archaeologist at the Polish Academy Sciences, tells Samantha Pope of the Ontario-based National Post. CT scans of the body indicate that the woman was between 20 and 30 years old at the time of her death.

Experts don’t know how the “mysterious lady” died, but given the high rate of maternal mortality in the ancient world, it’s possible that pregnancy could have factored into her demise, Ejsmond tells Szymon Zdziebłowski of state-run Polish news agency PAP.

Judging by the size of its head, the fetus was between 26 and 30 weeks old. It was left intact in the woman’s body—a fact that has intrigued researchers, as other documented instances of stillborn babies being mummified and buried with their parents exist. What’s more, four of the mummy’s organs—likely the lungs, liver, stomach and heart—appear to have been extracted, embalmed and returned to the body in accordance with common mummification practices. Why did the embalmers not do the same with the unborn baby?

Perhaps, Ejsmond tells CNN, the fetus was simply too difficult to remove at this stage of development.

Alternatively, he says, “Maybe there was a religious reason. Maybe they thought the unborn child didn’t have a soul or that it would be safer in the next world.”

The fetus’ discovery is particularly important because “pregnancy and traumatic complications [typically] leave little or no osteological evidence,” write the authors in the study. The mummy thus opens up new pathways into the study of perinatal health in the ancient world.

Next, reports PAP, researchers plan to analyze trace amounts of blood in the woman’s soft tissue in hopes of gaining a clearer picture of her cause of death.

“This is our most important and most significant finding so far, a total surprise,” Ejsmond tells the AP. “It opens possibilities of learning about pregnancy and treatment of complications in ancient times.”

The mummy also raises tantalizing questions about the place of unborn babies within the Egyptian mythology of the afterlife.

As the study’s authors ask, “The case study presented here opens a discussion into the context of the studies of ancient Egyptian religion—could an unborn child go to the netherworld?”

How Samos city in Calabria was founded on the same latitude as Samos island in the Aegean?

According to tradition, Samos in Calabria was founded in 492 BC by Greek settlers who came from the island of Samos in the Aegean Sea to escape the invasion of the army of King Darius I of Persia.

The colonists reached the coast of the Ionian Sea and moved inland, near Fiumara La Verde, to Rudina, in the territory of the Epicephyrian Lokrians. Soon the city grew rapidly and extended its boundaries from Capo Bruzzano to the present Gerace.

They built a large port that connected the city of Samos with the nearest Greek islands, and thanks to its maritime, port and trade activity, it achieved a remarkable social and cultural development and became an important transport hub in the heart of the Ionian Sea.

It is believed that Samos Calabria is the birthplace of the famous sculptor Pythagoras of Rhegium. Around 1530 Samos was completely destroyed by a flood that lasted seven days and seven nights. Since then the name of the city was changed to Crepacuore and later to Precacore.

Today, in its place is the small village of Precacore, known for its ruins of Greek-Byzantine art and therefore often visited by foreign tourists. Many of these works of art have been recently restored.

Ancient paths lead to the ruins of the ancient site of Samos and walking tours are organized. Ancient Samos in Magna Grecia is the twin of Samos in Greece.

What is still an unsolved mystery is how they knew and built their city in an almost straight line (northern latitude) with Heraion of Samos, which intersects with Samos of Triphylia and Samis of Kefalonia of Homer?

This means that, for example, in the 5th century, the latitude was already known. Without it, it was not possible to go out to sea and return safely. Undoubtedly, they knew it thousands of years ago!

The Life and Work of the Multi-scientist and great Philosopher Aristotle

by the archaeologist editor group

Since the evidence gathered by archaeologists is so abundant that many speak of the discovery of Aristotle's tomb in ancient Stageira, let us look at what we know about this great philosopher.

According to what we know, he was born in Stageira in 384 BC and died in Chalkida in 322 BC. At the age of 17 he entered Plato's Academy in Athens, where he remained until the age of 37. There he is associated with Plato himself as well as with Eudoxus, Xenocrates, and other thinkers.

His works relate to many sciences, such as physics, biology, zoology, metaphysics, logic, ethics, poetry, theater, music, rhetoric, politics, etc., and form the first comprehensive system of Western philosophy. The period of maturity begins with biological research, the results of which constitute the first systematization of biological phenomena in Europe. Aristotle's thought and teachings, briefly referred to as Aristotelianism, influenced philosophical, theological and scientific thought for centuries until the late Middle Ages.

Life and action

Aristotle was born in 384 BC in the ancient city of Stageira in Halkidiki, 55 kilometers east of modern Thessaloniki. His father Nicomachus was physician to the Macedonian king Amyntas III, who was Philip's father. Nicomachus, who according to the Suidae Lexicon had written six books on medicine and one on physics, considered the Homeric hero and physician Mahaon, son of Asclepius, as his ancestor. His mother Phaestia was from Chalkida and, like his father, belonged to the family of the Asclepiads. Aristotle's interest in biology was sparked in part by his father, as the Asclepiads taught their children anatomy from an early age; it is also said that Aristotle sometimes helped his father when he was young.

Aristotle was prematurely orphaned by his father and mother, and his guardianship was taken over by a friend of his father's, Proxenus, who had settled in Atarneus of Aeolis in Asia Minor, opposite of Lesbos. Proxenus, who cared for Aristotle as if he were his own child, sent him to Athens at the age of 17 (367 BC) to become a student of Plato. In fact, Aristotle studied at Plato's Academy for 20 years (367 - 347), until the year his teacher died. In the Academy environment, he amazed everyone and even his teacher with his intelligence and philanthropy. Plato called it the "dissertation spirit" and the house of the "reader's house".

When Plato died in 347 B.C., the question arose of a successor in the leadership of the school. Precedence for the post was given to Plato's three best students, Aristotle, Xenocrates, and Speusippus. Aristotle then left Athens with Xenocrates and settled in Assos, a city on the Asia Minor beach, opposite of Lesbos. Assos was then ruled by two Platonic philosophers, Erastos and Koriskos, to whom the ruler of Atarneas and old student of Plato and Aristotle, Hermias, had left the city. The two friends, governors of Assos, had founded a philosophical school there as a branch of the Academy.

In Assos, Aristotle taught for three years and, together with his friends, achieved what Plato could not. They were closely associated with Hermias and influenced him so that his tyranny became milder and more just. But the end of the tyrant was tragic. Because he anticipated the Macedonian campaign in Asia, he allied himself with Philip. Therefore, the Persians captured him and left him to die on a martyr's cross.

In 345 BC, on the advice of his student Theophrastus, Aristotle crossed to Lesbos and settled in Mytilene, where he stayed and taught until 342 BC. In the meantime, he had married the niece and stepdaughter of Hermias, Pythiada, with whom he had a daughter who took her mother's name. After the death of his first wife, Aristotle was later in Athens with Herpyllida from Stageira, with whom he had a son, Nicomachus. In 342 B.C. he was invited by Philip to Macedonia to take charge of the education of his son Alexander, who was then only 13 years old. Aristotle eagerly set about the task of educating the young heir. He took care to instill in him the Panhellenic spirit and used the Homeric epics as an educational tool. Alexander's education took place sometimes in Pella and sometimes in Mieza, a city whose ruins have been brought to light by archeological excavation; it was located at the foot of the mountain on which today's Naoussa in Macedonia is built. There he was informed of the death of Hermias in 341 BC.

Aristotle remained at the Macedonian court for six years. When Alexander crushed the resistance of the Thebans and restored peace in southern Greece, Aristotle went to Athens (335 BC) and founded his own philosophical school there. For the foundation of his school he chose the Gymnasium, also called Lyceum, between Lycabettus and Ilissos, near the Dioharis Gate. The site of the Gymnasium was recently discovered during the excavations for the construction of the new Goulandris Museum behind the Byzantine Museum of Athens in Rigillis Street. This historic excavation site is currently being renovated so that it can be visited. There was a grove dedicated to Apollo and the Muses. With the money generously given to him by Alexander, Aristotle erected magnificent buildings and arcades called "Peripatoi"(walks in Greek). Perhaps that is why his school was called "Peripatetic school" and his students "Peripatetic Philosophers".

The school was organized according to the standards of the Platonic Academy. Classes for advanced students were held in the morning ("eothinos peripatos") and for beginners in the afternoon ("peri to deilinon", "evening walk"). The morning classes were purely philosophical ("auditory"). The afternoon "rhetorical" and "external".

The school had a large library and was so well organized that it later served as a model for the founding of the libraries of Alexandria and Pergamon. Aristotle collected maps and tools useful for teaching physics. Thus, the school soon became a famous center of scientific research. In the thirteen years that Aristotle spent in Athens, he created most of his work, which by its scope and quality evokes our admiration. For it is quite amazing how a single person could gather and record so much information in such a short period of time.

When the news of Alexander's death arrived in 323 BC, the supporters of the anti-Macedonian party thought they had found in Aristotle an opportunity to take revenge on the Macedonians. The priesthood, represented by the hierophant of the Eleusinian Demeter, Eurymedon, and the school of Isocrates with Demophilus accused Aristotle of blasphemy ("blasphemous writing") for erecting an altar to Hermias, writing the Hymn to Areti(Virtue), and the epigram on the statue of Hermes at Delphi. However, realizing the true motives and intentions of his accusers, Aristotle traveled to Chalkida before his trial (323 BC). He stayed there in the house he had received from his mother, together with his second wife Herpyllida and his two children Nikomachos and Pythias.

Aristotle died in Chalkida between the 1st and 2nd of October of the year 322 B.C. of a stomach disease, in sadness and melancholy. His body was taken to Stageira, where he was buried with great honors. His fellow citizens declared him an "inhabitant" of the city and erected an altar over his grave. In his memory they established a festival, the "Aristoteleia", and named one of the months "Aristoteleios". The square where he was buried became the seat of the Parliament.

When he left Athens, he left the direction of the school to his pupil Theophrastus, whom he considered most suitable. Thus, the intellectual institution of Aristotle continued to radiate even after the death of the great teacher.

The work of the author

The Alexandrians estimated that Aristotle wrote a total of about 400 books. Diogenes Laertius calculated his work in verse and found that it amounted to 45 myriads, exactly 445,270 verses. A large part of his work has been lost. It belonged to the category of public or "external" courses and was written in a dialogic form. Of them, only the State of Athens has been preserved in a papyrus found in Egypt. The works that survive today correspond to the lessons that Aristotle gave to his advanced students, which are described as "auditory or esoteric". Therefore, they are written in continuous speech rather than dialogs. The list of Hesychius (appended to the biography of Aristotle) contains 197 titles of works and essentially coincides with the list of Diogenes Laertes.

The epic poem of Iliad on a map: All the Homeric heroes and their origins

This map is inspired by the “Achaeans and Trojans” map on Greek Mythology Link, a website created by Carlos Parantas, author of the "Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology".

It shows all the heroes of the Iliad and their origins in a unique representation of the major and minor characters of the immortal Homeric epic, both on the side of the Achaeans and the Trojans.

So if you want to refresh your knowledge about the "divine" Achilles, Odysseus, the sons of Atrea, or if you are simply touched/moved by Homer's epics, you should take a look at the map below:

click here to enlarge

Greece: A clay inscription with the verses of the Odyssey is exhibited In the Archaeological Museum of Olympia!

The clay inscription P15632 with the first 13 verses of the rhapsody Ξ of the Odyssey (Odysseus' encounter with Eumaeus) is exhibited in the Archaeological Museum of Olympia.

It is a recent find, coming from the Roman cemetery at Fragonissi, 1.5 km east of Olympia, and it was used as a building material in a funerary monument from the 3rd Century AD.

It was found in 2018 and is considered one of the most important archaeological discoveries of the year worldwide!

According to the research data, the inscription is the oldest preserved fragment of the specific verses and at the same time one of the oldest texts of the Homeric epics from the Greek area (apart from shells or vases with verses from the Homeric epics).

This underlines the great importance of the find, but also its uniqueness as an archaeological, epigraphic, philological and historical testimony.

This is the oldest song in the world and was written 3.400 years ago - Listen to it!

Music has always been more than just a mild form of entertainment for mankind.

Artists find in music a way to express their emotions, and for music lovers, it is a way to enhance or soothe feelings.

Early forms of music were used by the Vikings as war music to motivate and encourage warriors. The first forms of music used for entertainment date back to the pre-mediaeval period.

Recently, however, it has been discovered that music as a form of entertainment is much older than that, about 3400 years to be exact. This discovery was made using a piece of paper in the Syrian city of Ugarit.

Professor Anne Draffkorn Kilmer, who works as a curator at the Lowie Museum of Anthropology in Berkeley, spent fifteen years deciphering the clay tablets that a French archaeologist discovered and excavated in Syria in the early 1950s. The clay tablets were confirmed to be "a complete hymn that is the oldest surviving song in the world".

Professor Kilmer of the University of California worked with her colleagues Richard L. Crocker and Robert Brown to create a record of the song found on the discovered tablet, which had been named "Sounds from Silence".

With the approach taken, Professor Kilmer was able to define a harmony rather than a melody from individual notes. The likelihood of the number of syllables unintentionally matching the note numbers is incredibly high. This extensive research revolutionized the concept of the origins of music and Western culture.

This is how the song sounds in a more modern version:

It is believed that this song was sung with the flute, which is also considered the oldest instrument. What is also very interesting and questions the age of this song is the fact that the origin of the flute dates back to 67,000 years!

Netherlands: Rare luxury wedding dress found in 17th century shipwreck

In 1660, a ship carrying luxury goods sank off the coast of the Dutch island of Texel. Nearly four centuries later, few items had been recovered from the unknown wooden Dutch merchant ship.

But as the mud and sand covering the wreck receded, a few broken chests were revealed. Four years later, divers recovered these chests and brought them to the surface.

The chests contained impressive and rare items, according to researchers at the Kaap Skil Museum in the Netherlands, where they are on display. Luxurious clothing, textiles, silverware, books bound in leather and other items likely belonged to people from the higher social classes.

Among the most impressive pieces are two almost intact dresses: a silk dress and a wedding gown. Few fabrics or garments from the 17th century survive today, and it's even rarer to find them in shipwrecks because they wear out very quickly.

"When I first saw the clothes, I was very moved," said Amy de Groot, textile conservator and exhibition consultant. "Clothing is something so personal. You hold something in your hand that someone has worn. How close can you get to someone who lived in the 17th century?"

Courtesy Museum Kaap Skil

Made for a special occasion

The silver dress, unveiled in November 2022, will be displayed in an exhibit at the Kaap Skil Museum that features items recovered from the wreck of the Palmwood, as it is known.

The two dresses are made of expensive silk and were found in the same chest. The style of the silk dress is reminiscent of Western European fashions between 1620 and 1630, and the dress probably had silver or gold buttons, a stand-up collar of linen or lace, and other embellishments. Although it is now white, red and brown, researchers believe it was originally monochromatic. Despite the elaborate design and expensive fabric, the dress was probably intended for everyday wear.

For the silver wedding dress, on the other hand, scientists estimate that it was made for a special occasion. It features woven-in silver thread motifs that look like intertwined hearts, as well as silver embellishments.

"It's incredible what we have discovered here, it's one of the rarest historical finds ever" said Maarten van Bommel, a researcher and professor of conservation science at the university of Amsterdam. "There are perhaps only two such dresses in the entire world. And both are located here on Texel" he added.

The experts removed the salt from the dresses and then stored them in special display cases filled with pressurized nitrogen, which removes oxygen and thus prevents deterioration, Ewing explained.

"Thanks to this solution, we believe we can display the dress and other findings for a long period of time without damaging them," he added.

The ship was transporting belongings of a wealthy family

Knitted silk socks, a robe, a red bodice and a beauty set for a woman were found in the same chest as the dresses. Researchers were surprised to find that none of the dresses were the same size, which is why they believe the items likely belonged to a family traveling together.

The ship could have been transporting the belongings of a wealthy family to another country, said Arent Vos, an archeologist at the museum. The velvet robe, which may have been a caftan, could have come from the Ottoman Empire or Eastern Europe. Bright red color was very popular in the 17th century, according to the museum's researchers. The grooming set consists of a silk brush, the remains of a pillow, a comb and a table mirror decorated with silk velvet.

The other chests contained 32 books bound in gilded leather, one of which had the coat of arms of the Scottish-English Stuart royal family. According to experts, the bindings of books from England, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Poland date back to the 16th and 17th centuries.

Catastrophic storms had sunk 500 to 1,000 ships

Also recovered from the wreckage was a broken silver goblet similar in style to those made in Nuremberg in the late 16th century. On the lid of the cup is depicted the god Ares. The divers also unearthed a navigational instrument used by Dutch ships that bears the initials of its maker, H.I., and the date 1626.

Along the east coast of Texel lie hundreds of shipwrecks. Destructive storms had sunk 500 to 1,000 ships before trade routes stopped using Texel's shipping channels in the second half of the 18th century. Since the 1970s, about 40 ships have been identified, but most have yielded few finds.

Many of the ships disintegrated over time - but wrecks that were immediately covered by mud and sediment showed a slower rate of decay. Divers first discovered the Palmwood wreck in 2010 at Burgzand, in the Wadden Sea east of Texel.

High-quality hardwood logs were found on the top layer of the wreck, which probably belonged to the deck - hence the name given to the ship by researchers, who were unable to determine its identity.

"The area around Texel is full of wrecks, and we expect divers to be constantly on the lookout," Ewing said. "These wrecks, mostly Dutch merchant ships from the 17th and 18th centuries, are priceless treasures that reveal history and heritage to us. We believe more wrecks will be discovered in the next year."

The site of the finds, at the foot of the Ammertenhorn, at the end of summer 2022. © Archaeological Service of the Canton of Bern, Regula Glatz

In the Alps, a hiker unintentionally finds an ancient Roman shrine to mountain gods.

Being a professional archaeologist must occasionally be frustrating. Here you are laboring away on years-long excavations in the sweltering desert or icy English rain, hoping to find a tiny clue about ancient burial rites or something — only for some rogue to wander up a mountain one day and unintentionally stumble upon a long-lost shrine to the Ancient Roman mountain gods.

The Alps rarely yield solitary Roman coins, but this finding stands out for the quantity and position of the coins.

Even though our investigations are just getting started, we believe this is a sacred location.

A Roman coin on the site of the excavations. © Archaeological Service of the Canton of Bern, Regula Glatz

People made a sort of pilgrimage there to leave votive offerings—mostly cash, but also other items—asking or thanking the gods.

A lone hiker discovered a solitary old coin buried among the wreckage in 2020, which was the first indication that something unusual may have been going on in the area.

But, it soon became clear that this high-altitude spot was concealing much more than just a few pieces of lost change after reporting the discovery to the local authorities.

The votive plaque found at the foot of the Ammertenhorn. © Archaeological Service of the Canton of Bern, Markus Detmer

According to Newsweek, the team has so far uncovered 100 antique Roman coins, 59 Roman shoe nails, 27 tiny rock crystals, a brooch, and a piece of a votive plaque with a leaf design.

Yet even for the modern excavation team, getting to the location was challenging because it was 2,590 meters (almost 8,500 feet) above sea level and far from any known crossing spots.

It is clearly not a pass because it is far from any populated areas, both now and during the Roman era.

All of this points to a location that was very significant to the ancient people who left those artifacts behind.

The research team speculates that the area's naturally occurring rock crystal formations may play a role in its significance.

One of 27 rock crystals found at the foot of the Ammertenhorn. © Archaeological Service of the Canton of Bern, Regula Glatz

This kind of item is frequently thought of as an offering.

It is possible that the elevated plateau that sits between the Wildstrubel massif and Ammertenhorn's distant peaks was once a sacred site.

It's not entirely surprising considering that the location is only 19.3 kilometers (12 miles) from Thun, which is home to multiple Roman temples, including one specifically dedicated to the Alps' goddesses.

Clearly, there was a religious importance to the mountains, according to Gubler.

This location is intriguing because it demonstrates that the local Romans traveled up and near to the mountains to leave votive offerings, in addition to worshiping them from a distance.

Using Magnetic Fields, Long-Lost Underwater Civilizations Might Be Discovered, Scientists say

Off the coast of the UK, magnetic fields have the potential to be a useful tool in the search for vanished human sites.

There is optimism that this method might be used to uncover long-lost civilizations all across the world. A forthcoming effort will utilize magnetometry data to scour Doggerland, the flooded area of land that connected Britain to continental Europe until the end of the ice age.

The investigation was conducted by the University of Bradford in the UK's Faculty of Archaeology and Forensic Sciences.

Underwater archaeology can be a grueling job, but magnetometry data can make it much easier. Image credit: Vittorio Bruno/Shutterstock.com

They intend to carefully examine the magnetometry data obtained from a section of the North Sea and seek for any odd abnormalities that might point to the existence of ancient buildings.

Since some of the largest prehistoric towns in Europe are believed to have existed there, the team is especially eager to employ these techniques to search for signs of human activity beneath the North Sea.

Doggerland was a lush and diversified habitat that probably attracted prehistoric people and other animals until it was flooded more than 8,000 years ago.

The North Sea has been dug up for a variety of archaeological finds, including mammoth bones, red deer antlers, hunting gear, stone tools, and even a Neanderthal head.

We know little little about the inhabitants and the civilization that previously flourished here, despite the promise that lies beneath the North Sea.

Although the growth of wind farms in the North Sea is assisting Europe in moving away from fossil fuels, it also runs the risk of upsetting undiscovered archaeological monuments.

One of the final major issues facing archaeology is the exploration of the underwater terrain beneath the North Sea.

Map showing the hypothetical extent of Doggerland (c. 10,000 BCE), which connected Great Britain and continental Europe. Image credit: Max Naylor via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Due to the North Sea's quick expansion as a source of renewable energy, achieving this has never been more important.

Very little of the world's waters has been investigated, much less for archaeology.

Despite this, technological developments continue to demonstrate that the coastlines are hiding a wide variety of signs of early human activity, including proof of long-lost civilizations.

The prospects for marine archaeology are bright because of initiatives like the University of Bradford's and numerous others.

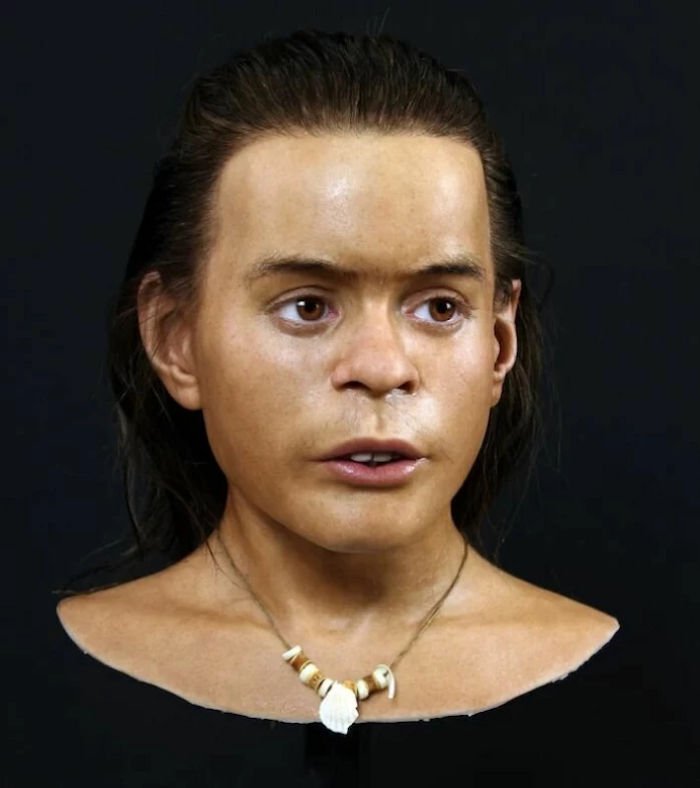

A full reconstructed figure of Vistegutten at a new permanent exhibition in Jæren. Oscar Nilsson has equipped him with a fishing spear and a fishing hook. (Photo: Oscar Nilsson)

Scientists have recreated the face of Norwegian child who lived 8,000 years ago

Scientists have recreated the visage of a Stone Age youngster who lived in Norway using DNA analysis and contemporary forensic procedures.

The Vistegutten, a 14-year-old kid from Viste, passed away.

It's unclear why he died at such a young age because it seemed he was in good condition.

The young boy was interred in the tiny Vistehola, a cave in southwest Norway that is situated just north of Stavanger.

possibly the same tiny cave where his parents formerly resided.

He is the most well-preserved member of Norway's Stone Age population.

Vistehola is located 10 kilometres northwest of Stavanger city centre. This is one of the most famous settlements from the Stone Age in Norway. Here, the skeleton of Vistegutten was found during an archaeological excavation in 1907. New methods have made it possible to extract DNA from the skeleton. (Photo: Jarle Vines / Wikimedia)

The boy's remains were discovered in Vistehola in 1907 while archaeologists were doing an excavation. His height was barely 125 cm.

The youngster has consumed as much food from the sea as from the land, according to new research techniques.

Those who lived close to the beach in Jaeren could eat cod, seal, and wild boar. Likewise were nuts and shellfish. Vistegutten was a little man, even for a Stone Age man.

In Norway, adult Stone Age men were most likely between 165 and 170 centimeters tall. The women's height ranged between 145 and 155 centimeters. Both sexes possessed powerful bodies, which Vistegutten also exhibited.

In Norway at the time, people frequently had prominent cheekbones and eyes. The boy had likely had quite dark skin.

Life at Jæren was probably good when Vistegutten lived there. The landscape was covered in deciduous forests with wild boars, moose and deer. The boy has also eaten a lot of food from the sea. The climate was milder than today and attracted people from the south to Norway. Examinations of the skeleton tell us that Vistegutten did not have any serious illnesses. He hasn't starved either. When he died, he was buried under the family's 'living room floor' inside the small cave. It must mean that they wanted to have the little boy close to them after he was dead. (Photo: Oscar Nilsson)

Oscar Nilsson's reconstruction is based on Genetic analysis.

It also builds on a 2011 effort in which scientists from the University of Dundee in Scotland used a laser to scan the skull of Vistegutten and produce a 3D model of his head.

We now know more about his head shape thanks to a later DNA analysis, according to Denham. His complexion tone, hair color, and eye color are a little less certain to us. We therefore rely on the other Stone Age artifacts we have from Norway in this situation.

In the Ancient Stone Age, people did not live very long on average.

This was partly brought on by the tragic deaths of so many young children.

Living to be over 50 years old was common when people first entered adulthood. The cause of Vistegutten's early demise is still unknown.