The tomb of Alexander the Great will always remain a universal mystery, although from time to time several finds have been announced that "show" where he could be buried.

Dr. Elpida Mitropoulou of Archaeology talks about the discovery made by Greek archaeologist Liana Souvaltzi in 1990 and the mistake made by the government of that time.

The recent discovery of the giant granite sarcophagus in Alexandria, Egypt, has rekindled hopes of solving one of the greatest archaeological mysteries of all time: what happened to the dead body of Alexander the Great and where it is buried.

Theories abound, but according to Elpida Mitropoulou, Ph.D. of archaeology at the University of London (UCL), senior research fellow at the University of Birmingham and former researcher at the University of Berlin, author of the article "The Four Tombs of Alexander the Great," the tomb of the great general is located in Egypt's Shiva Oasis, at the site of El Maraki, where Liana Souvaltzi identified a gigantic funerary monument of more than 500 square meters in the 1990s.

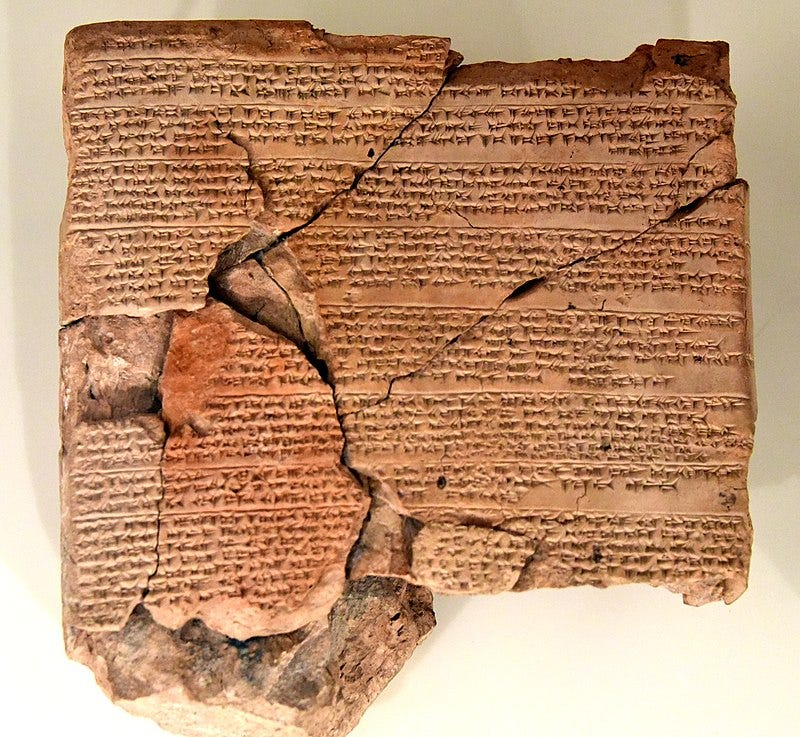

The two inscriptions found there, each a copy of the other, bore the words "Alexander Ammonus Ra," but the special commission sent by the Greek government to investigate them "mistakenly concluded that both inscriptions were Roman and had nothing to do with Alexander the Great," Ms. Mitropoulou notes.

As a result, Ms. Souvaltzi's excavation permit was not renewed. As the archaeologist explains, one of the two inscriptions was actually Roman. "When the Emperor Trajan, who greatly admired the Greek emperor, visited the tomb of Alexander the Great, he wanted to take some of his glory with him - so he asked a sculptor to copy the original inscription and put his own signature at the end. Then he took the original inscription and placed it in the temple, and in the place where the original had stood, he placed the Roman copy.

The additional elements that "testify" to the tomb

However, the inscriptions are not the only evidence that it is a royal tomb. "A disc with two snakes, the lions guarding the entrance of the tomb and the buttresses testify that it is a royal tomb and a deified man" Ms. Mitropoulou points out.

According to Ms. Mitropoulou, "Alexander the Great died suddenly and was initially buried in Memphis. However, Ptolemy I then had him secretly transferred to Siwa, mainly out of fear of Alexander the Great's successor, Perdiccas, who came to Egypt demanding the body of the dead king.

The first time, Ptolemy managed to trick him by giving him another body, but the second time Perdiccas arrived in Egypt and demanded his body, he was killed by Ptolemy's horsemen. With Perdiccas now out of the way, Ptolemy ordered an inscription containing all the information about the tomb's occupant.

When Ptolemy II founded Alexandria, he erected a building next to his palace that he called "Signal" and decided to bring all the pharaohs there, including Alexander. With the introduction of Christianity as the only religion by Theodosius the Great in the 4th AD century and the massive destruction of the ancient temples in Egypt and Greece, Alexander was again brought to "Shiva".

The veil of mystery falls for Alexander the Great: "His tomb was revered as the temple of a god..."

Archaeologist Kalliopi Papakosta has been focused for 20 years on her mission to discover the tomb of Alexander the Great, one of the world's greatest archaeological mysteries.

In the Salalat Gardens, the park in Alexandria, Egypt, archaeologist Kalliopi Papakosta searches for traces of Alexander the Great, and a few years ago she came across another important find that revived her hopes.

Papakosta's assistants called her to examine a piece of white marble that had been found in the park. She herself had been disappointed with the excavation, but when she saw the white stone shimmer, she gained new hope. "I was hoping it was not just a piece of marble," she said, and in the end she was right, as National Geographic writes in its tribute.

The artifact turned out to be an early Hellenistic statue bearing the seal of Alexander the Great. This was a strong incentive for the archaeologist to continue the excavations. Seven years later, Papakosta, who directs the Hellenic Research Institute of Alexandrian Culture, has dug dozens of meters beneath modern Alexandria and uncovered the ancient city's royal quarter.

"This is the first time the original foundations of Alexandria have been found," says Fredrik Hiebert, an archaeologist with the National Geographic Society. Archeologists believe that one of the greatest finds in archeology, the lost tomb of Alexander the Great, may be located at this site. Alexander the Great died in 323 BC at the age of 32, and the mystery surrounding his burial begins shortly thereafter with reports from historians showing why his discovery is a complex matter.

It is believed that Alexander's body was first buried in the ancient city of Memphis in Egypt and then in the city that bears his name. There his tomb was worshiped as a temple to a god.

But Alexandria and the tomb of its founder were threatened by nature. A decade before Alexander's birth, in 356 BC, the city was hit by a tsunami. This disaster marked the beginning of a long series of earthquakes and rising sea levels that continue to threaten Alexandria today.

As sea levels rose, the waters of the Nile Delta, where Alexandria is located, flooded the ancient part of the city at a rate of up to 0.25 centimeters per year. The city survived, but over time its foundations were buried and fell into oblivion, as did the site of Alexander's tomb.

Although ancient writers such as Strabo described the tomb, its location in relation to the modern city remains a mystery. There are records of nearly 140 officially sanctioned excavations, but all have failed.

Hope for a historical find keeps the Papakosta excavation alive, based on ancient evidence and a 19th century map of Alexandria. Modern technology is used to determine where to dig, such as special electrical tomography (ERT).

Using numerous methods, Papacosta uncovers more and more of the city's ancient royal quarter - including a Roman street and the remains of a huge public building that may hold clues to Alexander's tomb. But each discovery is a difficult task, as Papakosta had to develop a complex system of pumps and pipes to keep the area dry so excavations could continue.

As the years pass, Papakosta becomes increasingly convinced that she is closing in on Alexander's lost tomb. However, she tempers her optimism with a dose of realism. "Sure, it's not easy to find, but I am definitely in the center of Alexandria in the royal quarter and everything is in my favor. I have been persistent and kept going and will continue to do so," she says.