Beneath the waves of oceans and seas lie the silent ruins of once-thriving cities—frozen in time, shrouded in mystery, and steeped in history. These ancient underwater cities, long lost to natural disasters or rising sea levels, offer rare and tantalizing glimpses into early human civilizations. Far from being myth alone, sites like Dwarka in India, Pavlopetri in Greece, and Atlit-Yam in Israel challenge our understanding of the ancient world—and even hint at forgotten chapters in human development.

Let’s dive into the stories of these submerged cities and explore what they reveal about the ingenuity, resilience, and interconnectedness of early societies.

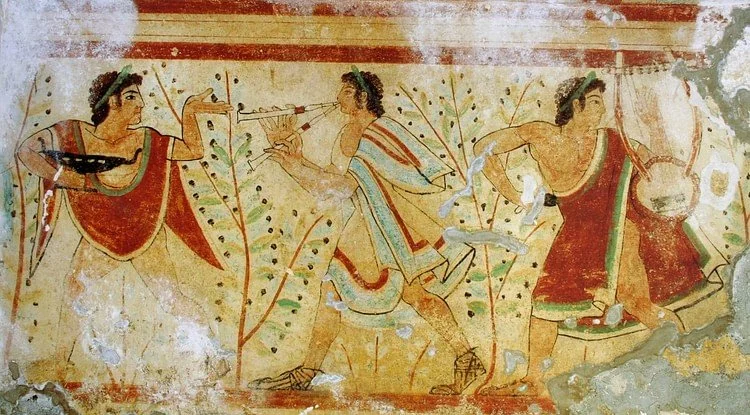

Pavlopetri: The World’s Oldest Submerged City

Location: Off the coast of Laconia, southern Greece

Estimated Age: ~5,000 years (dating to the early Bronze Age)

Discovered in 1967, Pavlopetri is widely considered the oldest known submerged city in the world. What makes it so extraordinary isn’t just its age—it’s the remarkable preservation of its urban layout. Streets, buildings, courtyards, and even a water management system are all clearly visible beneath the surface.

Archaeologists believe Pavlopetri was a center for trade and domestic life, and it offers rare insights into how early coastal societies functioned. The city was likely lost due to tectonic shifts or a sudden rise in sea level.

What it tells us:

Pavlopetri proves that organized, coastal urban planning was happening earlier than previously thought. It also underscores the vulnerability of ancient cities to environmental shifts—a theme that continues to resonate today.

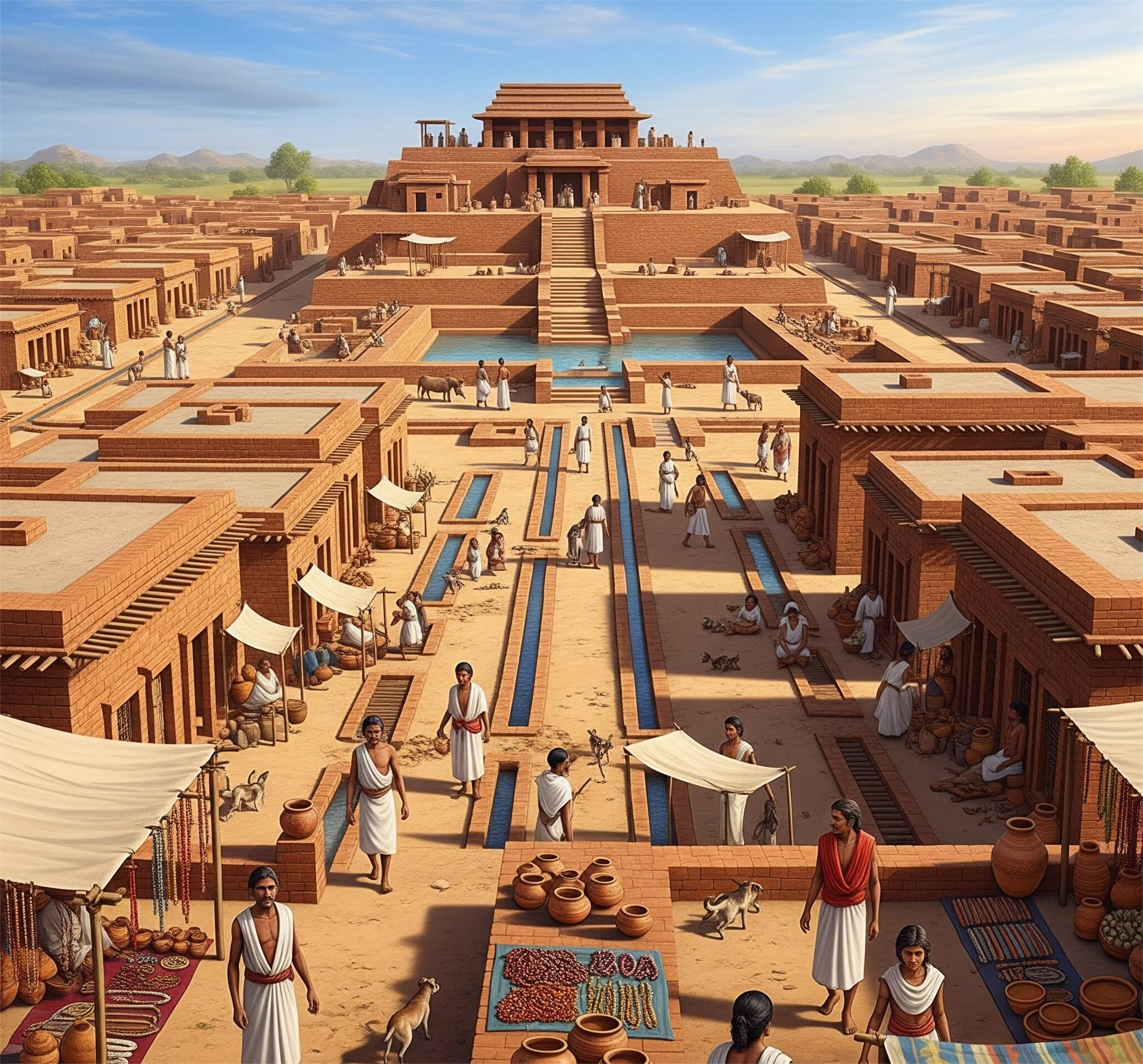

Dwarka: The Legendary City Beneath the Arabian Sea

Location: Gulf of Khambhat, western India

Estimated Age: Contested; possibly over 9,000 years old (according to some claims)

Dwarka occupies a unique place in both mythology and archaeology. In Hindu tradition, it is described in ancient texts as the magnificent city of Lord Krishna, submerged by the sea after his death. In the early 2000s, sonar scans and dives in the Gulf of Khambhat revealed large geometric formations, stone structures, and what some claim to be ancient ruins.

The findings are controversial. Skeptics argue that the artifacts may be natural formations or misdated, but proponents suggest that Dwarka could rewrite early Indian history, suggesting a highly advanced urban settlement predating known civilizations.

What it tells us:

If the underwater structures of Dwarka are proven to be man-made, they could challenge the timeline of organized civilization in the Indian subcontinent, pushing the development of cities much further back than previously thought.

Atlit-Yam: Prehistoric Life Beneath the Waves

Location: Off the coast of Haifa, Israel

Estimated Age: ~9,000 years (Neolithic period)

Atlit-Yam is a stunningly well-preserved prehistoric settlement discovered beneath the Mediterranean. This site contains houses, wells, hearths, human burials, and even a stone semicircle that may have had ritual significance—possibly the world’s oldest known example of a megalithic structure underwater.

Researchers believe the village was abandoned after a sudden tsunami, likely triggered by a volcanic eruption in the Mediterranean.

What it tells us:

Atlit-Yam reveals that early humans had complex societies and community planning long before the rise of cities like Babylon or Ur. The presence of agriculture, fishing, and ancestor worship shows an early shift toward settled life and religious practice.

A Global Phenomenon: Lost Cities Beneath the Sea

These are just a few among dozens of underwater sites around the world—from Yonaguni in Japan to Port Royal in Jamaica and the Bay of Cambay. Some are the result of cataclysmic earthquakes, others of slow sea level rise following the end of the Ice Age.

Collectively, these sunken cities help archaeologists reconstruct ancient coastlines, trade networks, and migration patterns. They also remind us that our ancestors were not static or isolated—they built thriving communities on the edge of the sea, often with remarkable skill and sophistication.

Echoes of Atlantis?

The discovery of underwater ruins often rekindles interest in the legendary city of Atlantis, first described by Plato as a technologically advanced society swallowed by the sea. While no definitive evidence of Atlantis has ever been found, submerged cities like Pavlopetri and Dwarka suggest that myths may sometimes contain kernels of truth—whether symbolic or historical.

Why These Cities Matter Today

Climate Change Lens: Studying ancient submerged cities helps scientists understand how human societies responded—or failed to respond—to environmental changes.

Technological Progress: Many of these ruins were found using advanced sonar and diving technology, pushing the boundaries of underwater archaeology.

Cultural Continuity: These sites reveal how people lived, worshipped, and interacted with nature, drawing direct lines from the past to modern coastal cultures.