One night in 373 BCE, the earth beneath the ancient Greek city of Helike shook violently and split apart. As homes and temples collapsed, a giant wave—a tsunami from the Corinthian Gulf—engulfed everything. Helike, the capital of Achaea, vanished from the map. No human remains were ever recovered by archaeologists.

For centuries, the city’s fate was cloaked in legend. It inspired Plato’s story of Atlantis, haunted Roman travelogues, and puzzled scholars. However, a new study published in the journal Land by a team of Greek and British researchers breathes new life into Helike’s story. As the study reveals, the city was destroyed multiple times—and each time, it was rebuilt nearby.

“The ancient inhabitants of the region consistently chose to rebuild in the same geographical zone,” note the authors, led by Dora Katsonopoulou, director of the Helike Project. “By adapting their way of life to the landscape and natural hazards, they consistently overcame the challenges.”

Their work, spanning over 30 years, is one of the most detailed case studies of human resilience in the face of disaster.

A Landscape in Constant Motion

Helike wasn’t destroyed just once. It went through successive cycles of life and destruction.

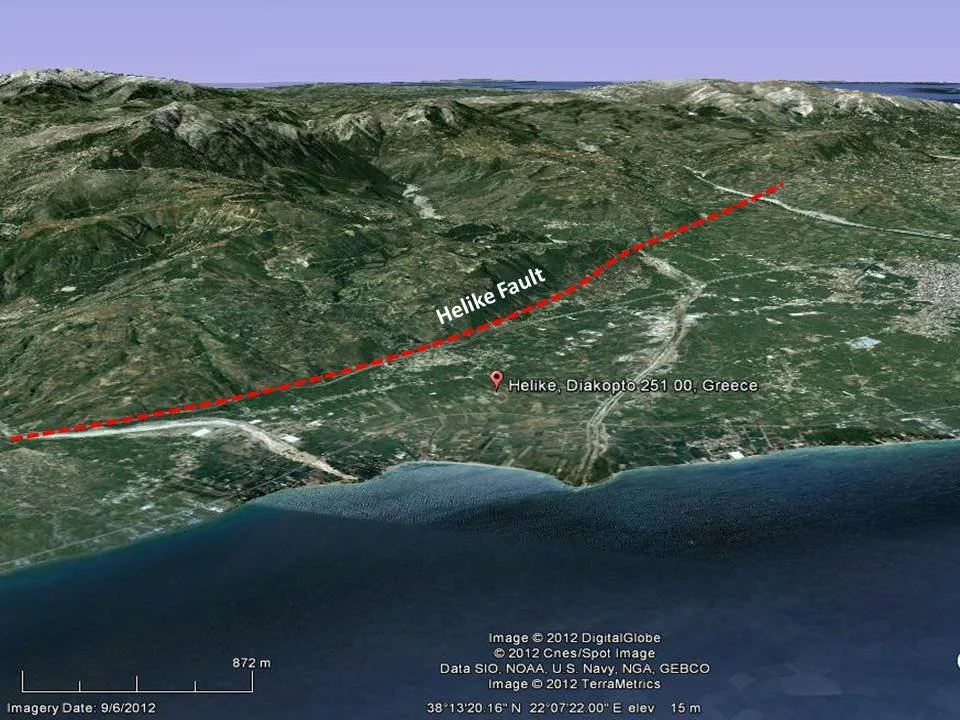

Founded during the Bronze Age on a fertile coastal plain between two rivers, the city had a strategic location for trade, but also a dangerous proximity to Europe’s most seismically active gulf. Roughly every 300 years, strong earthquakes and tsunamis struck the area.

Yet its people never truly abandoned the site. After each disaster, they relocated a short distance away and rebuilt. Following the catastrophe of 373 BCE, the survivors moved westward and established a new city. Archaeologists have discovered textile workshops at the site, suggesting rapid economic recovery.

Using sediment cores, stratigraphic analysis, and digital terrain modeling, researchers were able to map out these relocations. A major earthquake in 2100 BCE triggered a flood that buried a Bronze Age settlement. By Roman times, the same land had risen enough to host a major road.

The movement wasn’t random. Inhabitants remained rooted to place—but adapted to its changing form.

The Archaeological Footprint of Earthquakes

Excavations across the Helike plain have uncovered alternating layers of destruction and reconstruction. The soil bears the marks of seismic trauma: walls tilted at strange angles, pottery smashed in place, and—in one of the most haunting finds—the skeleton of a man buried alive under collapsed debris.

One trench revealed an until-now-unknown earthquake around 700 BCE, with a fault line cutting straight through building walls. Builders had tried to guard against future quakes by constructing on bedrock and using high foundations—suggesting early seismic awareness.

After the 373 BCE disaster, architecture changed: structures began to use polygonal masonry, more resistant to tremors. Following another major quake in the 1st century BCE, the city was relocated again, this time to the east.

During the Roman era, a road passed through the ruins, winding between half-collapsed workshops. When the traveler Pausanias visited in the 2nd century CE, this road was still visible.

Myth, Memory, and the Sea God

Ancient peoples tried to explain such destruction in their own terms. Aristotle attributed earthquakes to subterranean winds. Others saw the wrath of Poseidon, god of the sea and earthquakes, whose temple in Helike drew pilgrims from across Greece. For centuries, sailors claimed to see the bronze statue of Poseidon submerged, still holding his trident.

The historian Diodorus Siculus wrote: “A wave of enormous size, greater than any before, swallowed everything—people and homeland.” Other accounts mention that only the tops of Poseidon’s sacred trees remained visible above the water.

Yet modern excavations do not confirm the presence of a permanently submerged city. Instead, they point to a constantly shifting landscape: earthquakes that tilt the land, rivers that change course, lakes that appear and vanish. The “tsunami” of 373 BCE may also have involved inland flooding caused by landslide-created dams—an entirely plausible scenario for the area.

Lessons from the Past

What makes this study stand out is not just its geological accuracy—but its human story. The people of Helike did not despair in the face of destruction. They responded intelligently, inventively, and with adaptability.

Their city wasn’t bound to any single structure or layout. It was a persistent idea, tied to the land—but not fixed in place. This flexibility, the researchers argue, is the true essence of resilience. It’s a lesson worth studying by those designing cities today in areas vulnerable to earthquakes or rising seas.

As the researchers write: “The society of Helike demonstrated sustained resilience to disaster. One could say that, having faced severe environmental risks for generations, it learned from experience and developed effective solutions.”

Helike is not merely a buried ruin. It is a parable—of loss, endurance, and the long memory of the earth.

Source: Land journal / Helike Project