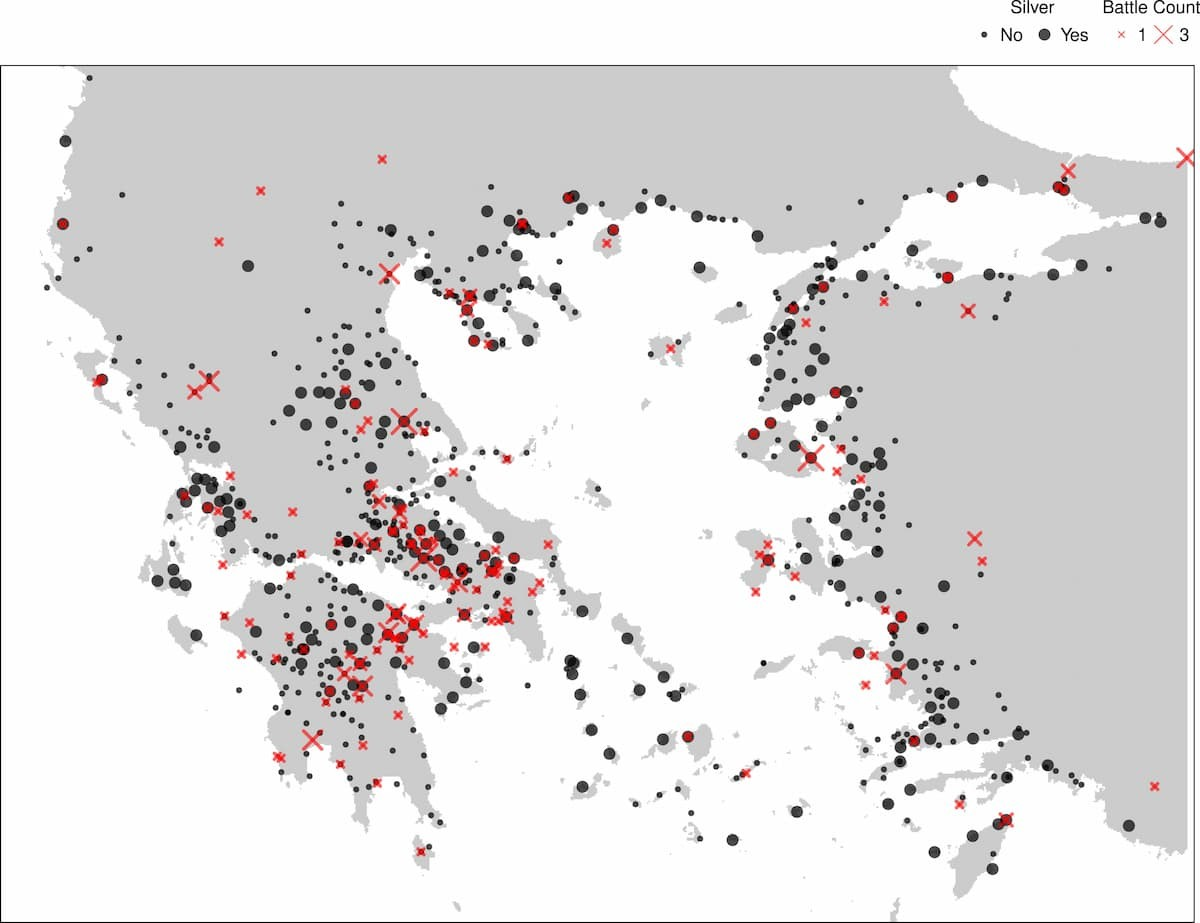

A map shows the spatial distribution of Greek city-states, highlighting regions where silver coinage was minted. It also displays the geographical locations of battles.

Photo: J. Adamson

A newly published study in the Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization offers an alternative explanation for the emergence of the ancient Greek city-state.

Rather than attributing its formation solely to war, geography, or internal politics—as is commonly believed—the study suggests that trade was the real driving force behind the development of these politically autonomous societies, which typically consisted of a city and its surrounding territories.

Specifically, the study emphasizes the unique advantages of each city, the ability to produce different goods, and how these differences led not only to economic exchange and prosperity but also to conflict.

The article, authored by Jordan Adamson, argues that natural resource variation—such as differences in vegetation or access to certain materials—led to productive specialization. This specialization generated wealth through trade, which in turn made communities targets for enemies and prompted the need for defense.

This, Adamson claims, is how the Greek polis—or city-state—came into being.

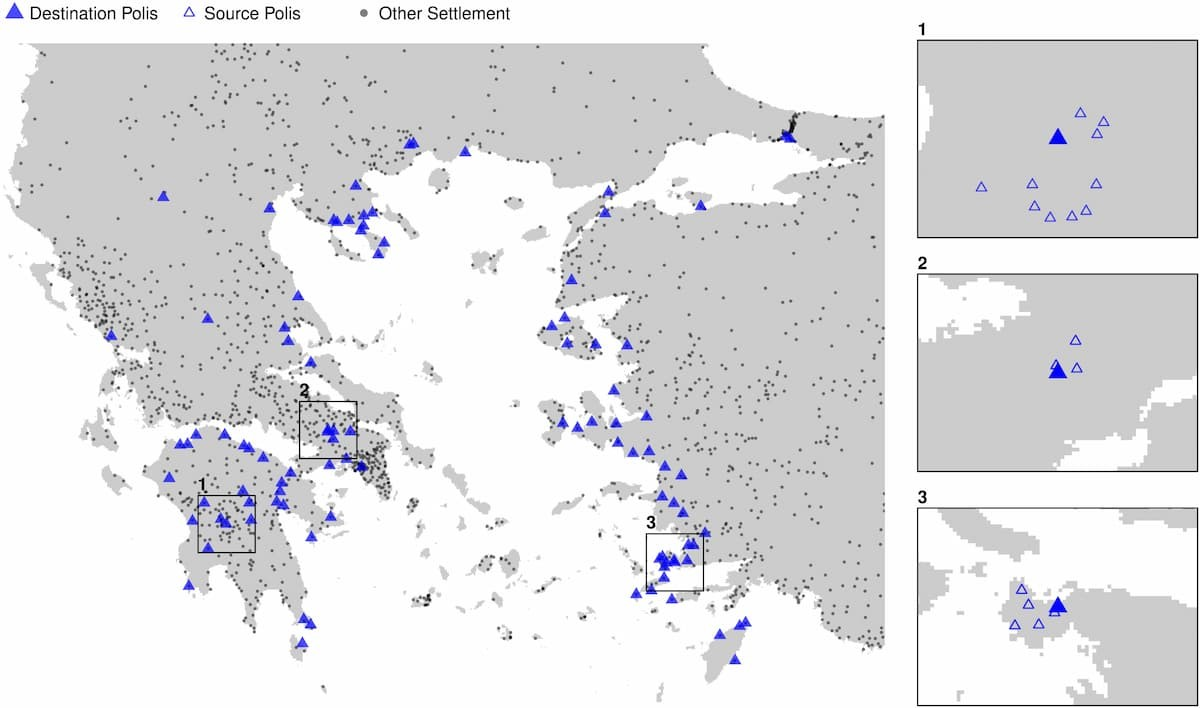

Map showing the spatial distribution of synoikismos.

The left panel displays all instances of synoikismoi. The three panels on the right highlight:

Megalopolis

Thebes

Halicarnassus

“Trade, based on comparative advantage, was a source of wealth and therefore became a target for raids,” Adamson explains. “This threat necessitated the creation of organized, defensive societies.”

Diversity and Natural Wealth as the Study's Core Insight

A key element of the study is a simple yet powerful concept: diversity in natural resources. Not all regions had equal capabilities when it came to producing goods.

Some areas were more agriculturally fertile, while others had access to mineral wealth, timber, or other resources. This variation created a natural incentive for exchange.

One of the maps used in the study shows the spatial distribution of settlements. The left panel depicts all settlements, while the three on the right highlight major city-states:

Megalopolis

Thebes

Halicarnassus

Photo: J. Adamson

Rethinking the History of the Greek City-State?

To support his hypothesis, Adamson compiled a database of 696 Greek city-states founded between 600 and 320 BCE. Using historical records, ecological maps, and archaeological data, he identified the cities’ locations, the surrounding vegetation, whether they minted silver coins (a reliable indicator of participation in trade), and whether they were near battlefields or areas where villages had been consolidated into new settlements (synoikismoi).

In ancient Greek culture, synoikismos refers to the formation of a settlement or city by a group of people who come together in a shared space to live, build infrastructure, and develop economic activities.

Key Patterns Identified

The study found that areas with greater natural diversity—where the difference between what a city could produce and what neighboring regions could offer was more pronounced—showed three notable traits:

Higher use of coinage

Greater involvement in conflicts

Increased likelihood of forming new settlements (synoikismoi)

According to Adamson, this pattern cannot be fully explained by the traditional "key factors" often emphasized in other research—such as proximity to the sea, access to rivers, or soil quality.

Instead, the data point more clearly to resource diversity as the underlying cause of city-state development—more so than those traditionally highlighted environmental factors.

When Defense Gave Birth to Cities

One of the most striking phenomena examined in the study is that of ancient Greek synoikismos: the creation of a new city-state through the merging of villages or communities—sometimes geographically, other times politically. Adamson interprets this as a collective response to a shared threat, namely plunder.

In other words, a wealthy trading city would become a target for attack. To protect themselves, neighboring communities might choose to unite and form a fortified settlement.

This is how cities like ancient Megalopolis came into being—founded shortly after a major conflict between Sparta and Thebes. This interpretation invites a new understanding of ancient warfare. According to Adamson, the Greeks recognized that the root of violence was often the desire to gain wealth.

“Military force,” he notes, citing historical sources, “was a natural means of resource acquisition.” In other words, not all conflicts were territorial expansions—some were raids on wealthy but poorly defended areas.

The study also examined the spread of silver coinage, which wasn’t widespread across all settlements.

Coinage, Trade, and Defense

Adamson argues that the presence of minted coinage signals that a city was embedded in active trade networks. His research found that cities with coinage were more often involved in battles and frequently featured in settlement consolidation processes.

The minting of silver coins became the dominant method of payment in all cities engaged in trade.

Strong Link Between Trade and Violence

The study makes a compelling case for a clear connection between trade and violence:

Where there was silver, there was interest; and where there was interest, war could break out.

At the same time, this dynamic spurred organization, defense mechanisms, and institutional development.

While the study focuses on ancient Greece, Adamson believes its findings are far from unique to that region.

Broader Implications

Similar patterns have been observed in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Anatolia, and even in pre-Columbian civilizations across North, Central, and South America. In all these cases, trade appears to have been the silent engine behind political organization.