For centuries, the unusually well-preserved body of an 18th-century clergyman has been the subject of local legends, speculation, and mystery.

According to local lore, the body of the parish priest—believed to have died from an infectious disease—was moved from its original grave to the crypt of St. Thomas am Blasenstein, a small church in a village north of the Danube River in Austria.

The remarkably intact state of the cleric’s body, with skin and soft tissues preserved, has long attracted pilgrims who believed the remains might possess healing powers.

But centuries later, an object resembling a capsule discovered during an X-ray of the mummy suggested a darker possibility—poisoning. Now, a team of scientists has shed new light on the enigmatic life and death of the so-called “dried-up priest.”

The breakthrough came following water damage in the crypt, which led to renovations and gave researchers a rare opportunity to perform high-tech analyses on the centuries-old remains.

The mummy remains in the crypt of a small church, sparking tales and legends about the priest’s life and death – Photo: J. Wimmer

“We took the mummy for several months to examine it with our specialist teams using imaging scans and other methods. Meanwhile, there was time to restore the site. It was a win-win situation,” explained Professor Andreas Nerlich, a medical professor at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich and lead researcher of the study.

Unlocking the Secrets of the Alpine Mummy

The mummy still rests in the crypt of the small church, continuing to inspire stories and speculation about the priest’s life and death.

Using CT scans, radiocarbon dating, and chemical analysis of bone and tissue samples, Nerlich and his team were able to confirm the mummy's identity and uncover the unique method that preserved the body in such exceptional condition.

A Preservation Mystery

With no visible signs of embalming, the remains of Franz Sidler von Rosenegg—an aristocratic priest who died in 1746 at the age of 37—were long thought to have been naturally mummified.

This made the results of the CT scan all the more surprising: the priest’s abdominal and pelvic cavities were packed with materials such as wood shavings, flax, and pieces of fabric. Additional toxicological tests revealed traces of zinc chloride and other elements.

“It was completely unexpected, because the outer body walls were totally intact,” Nerlich said.

To explain the contradiction—an untouched exterior with a packed interior—the team proposed that the materials had likely been inserted rectally. They believe the combination of absorbent and drying substances is what preserved the body so effectively, giving rise to the mummy’s nickname.

“The wood shavings and cloth would have absorbed bodily fluids. The zinc chloride would have had a drying effect and reduced bacterial activity in the intestines,” explained Nerlich, concluding that the preservation was not natural after all.

This method of mummification differs significantly from the well-known techniques of ancient Egypt, which typically involved cutting open the body. The procedure used on the priest has never before been documented in scientific literature, according to the study published in Frontiers in Medicine.

Nerlich suggests that while this method doesn’t appear in any known manuals from the era, it may have been a common practice in the 18th century—especially for preserving bodies that needed to be transported or displayed.

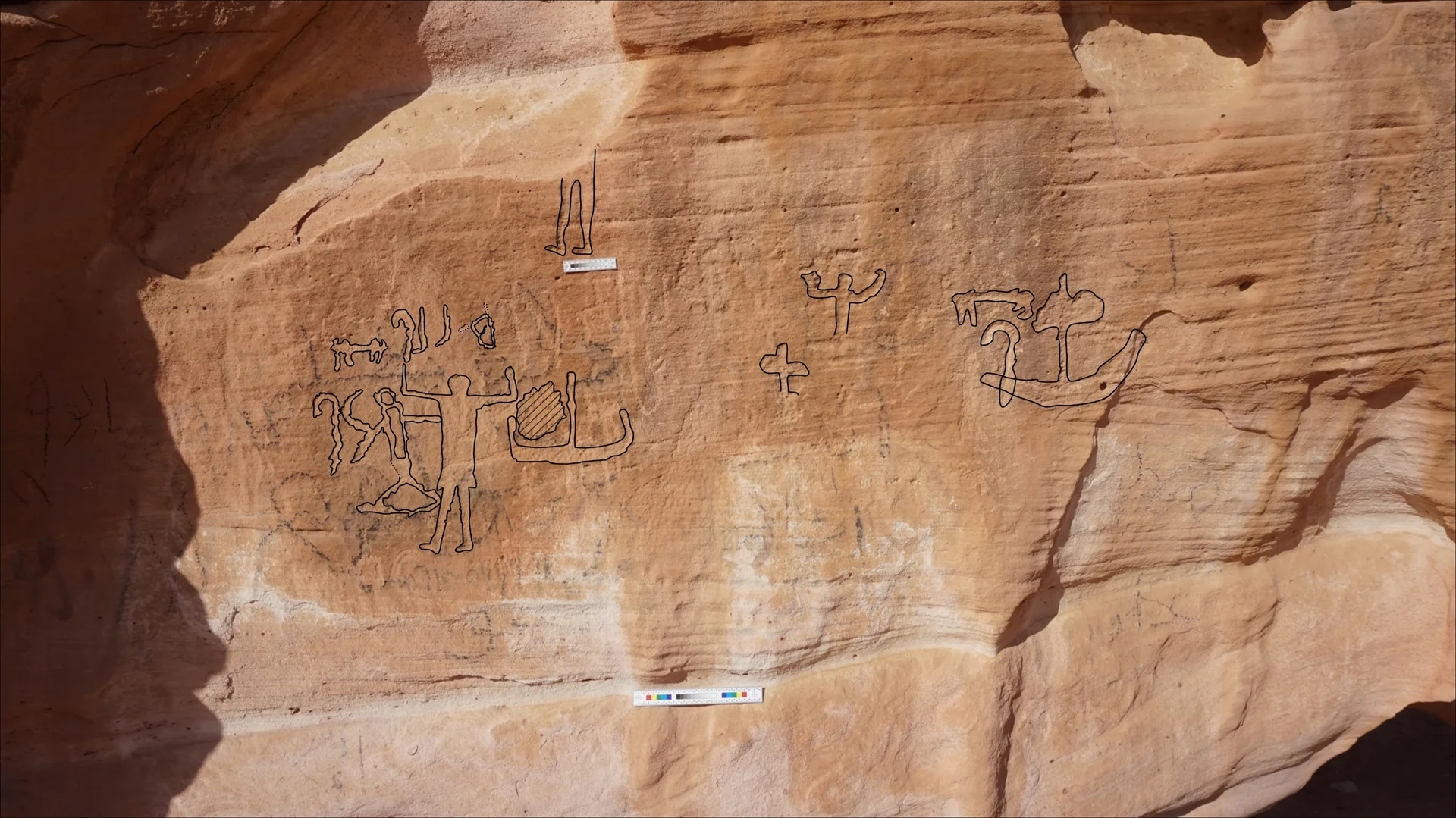

X-rays revealed a round structure about 1 centimeter in size inside the mummy’s abdomen, fueling a centuries-old theory that the priest had swallowed a poisonous capsule before his death – Photo: Msgr. Karl Wögerer, Kirchenstiftung Waldhausen/Strudengau

Gino Caspari, an archaeologist and author of The Book of Mummies: An Introduction to the Realm of the Dead, agrees. He believes that embalming techniques in the past were likely more diverse and widespread than previously thought.

Cause of Death Reconsidered

The findings also overturn long-standing theories about the priest’s death and burial. Contrary to earlier suspicions of poisoning, the study found no signs of toxic substances in his system. Instead, researchers now believe that the priest, a chronic smoker, died from advanced tuberculosis that led to acute pulmonary bleeding.

One X-ray from the year 2000 had revealed a small spherical object in the mummy’s abdomen—about one centimeter in diameter—which fueled theories of a swallowed poison capsule. However, Nerlich and his colleagues determined that the object, which had tiny holes at each end, was likely a bead from a rosary that became entangled in the embalming materials.

Moreover, the team found no evidence to support the idea that the body was first buried and then later relocated to the crypt. According to Nerlich, it’s far more likely that the priest’s remains were prepared for transport to his monastery, located 15 kilometers away—but for reasons lost to time, the journey never happened. The mummy stayed behind, entombed in the church crypt, preserving its secrets until now.