Golden Fleece to Golden Sands: Unearthing the True Story of the Argonautic Expedition - A Historical Exploration of Myth, Gold, and Ancient Metallurgy

The Golden Fleece and the Gold of the Phasis River

Recent Archaeological Surveys and Bronze Age Metallurgy

The Mycenaean Presence in Colchis

Deciphering 'ko-ki-da': The Linear B Conundrum and its Implications for Mycenaean History

Colchis: The Land of the Golden Fleece and its Historical Significance in the Ancient World

The Argonautic Expedition represents a crucial event in the ancient Greek heroic tradition. According to legend, the story revolves around the quest of Jason and the Argonauts for the Golden Fleece, a symbol of authority and kingship, which was held in Colchis. This pursuit has been immortalized in various works of literature, including the epic poem Argonautica. While the tale is steeped in mythology, historians and archaeologists have made intriguing attempts to identify a historical core behind the myth, exploring possible correlations with ancient metallurgy practices, trade routes, and cultural interactions.

The Golden Fleece and the Gold of the Phasis River

The Golden Fleece, the central object of the Argonautic quest, has been interpreted in many ways. The famous geographer Strabo argued that the Golden Fleece reflects the abundant gold of the Phasis River in Colchis. According to him, the fleece was a metaphorical representation of the gold-bearing sand collected by the local residents. This interpretation provides a plausible economic explanation for the myth, linking it to the extensive gold deposits in the region.

These gold nuggets, Strabo posited, were collected from the river using ox hides. After the hide was loaded with gold-bearing sand, it was then processed through a method known as cupellation. This was an ancient process of refining gold and other precious metals in which the metal was heated to a high temperature to separate it from its impurities. The impurities would oxidize, leaving behind pure gold.

Thus, the Golden Fleece could symbolize this ancient practice of gold extraction and processing, providing a link between the myth and the metallurgical techniques of the time. This method of gold extraction was not exclusive to the Colchis region; it was a well-known practice among many ancient civilizations. It was simple, required minimal equipment, and was quite effective in regions with abundant alluvial gold deposits, such as those found in the Phasis River.

Strabo, one of the most renowned geographers of the ancient world, made a significant contribution to the discourse surrounding the Argonautic Expedition's historical core. Born in 64 or 63 BC in Amaseia, today's Amasya, Turkey, he traveled extensively, gathering a wealth of geographical and historical knowledge, which he compiled in his magnum opus, "Geographica."

While it's impossible to definitively prove Strabo's interpretation of the Golden Fleece, his explanation offers a rich insight into the economic practices of the time and the intricate ways these practices may have been woven into the fabric of myth and legend. Moreover, it emphasizes the significance of interdisciplinary research in understanding the complex interplay between history, geography, and mythology.

Recent Archaeological Surveys and Bronze Age Metallurgy

Recent archaeological surveys have further bolstered the argument for a historical core to the Argonautic Expedition. Sophisticated objects dating back to the Bronze Age, made of precious metals, have been unearthed, revealing a thriving metallurgy based on rich local ores deposits in the Colchis area.

A significant find was made near Iolkos at the Mycenaean tholos tomb of Kazanaki, which dates back to 1350 BC. Among the items found were gold foils and discs, necklaces, and necklace beads. Intriguingly, the gold used in their manufacture was found to be alluvial gold, similar to that which would have been collected from the Phasis River. This suggests a direct connection between the gold of Colchis and the Mycenaean Greeks, particularly those in the palace elite of Iolkos, who resided in the Megaron of the Citadel of Dimini.

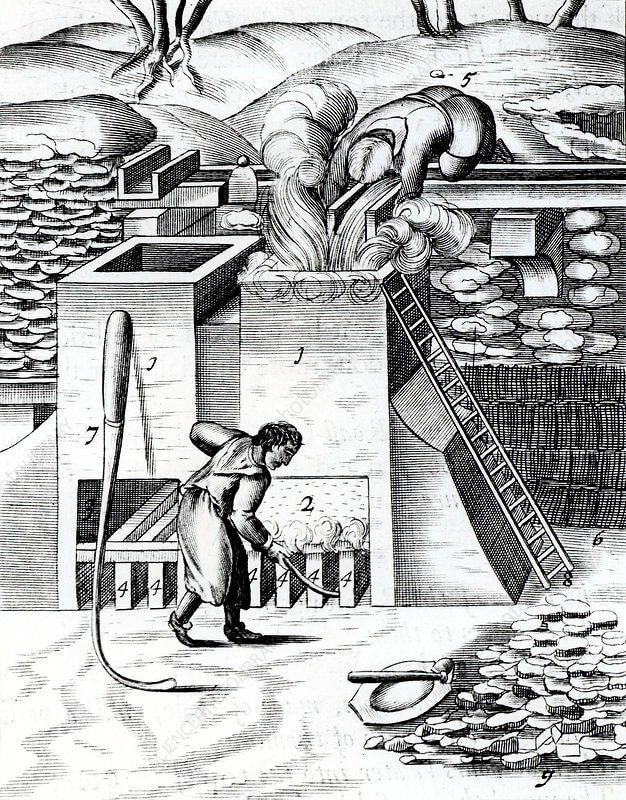

Roasting gold ore in order to recover the precious metal. From 1683 English edition of Lazarus Ercker Beschreibung allerfurnemisten mineralischen Ertzt- und Berckwercksarten originally published in Prague in 1574. Copperplate engraving. Credit UNIVERSAL HISTORY ARCHIVE / UIG / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

The Mycenaean Presence in Colchis

The archaeological data demonstrates that the Mycenaean Greeks had extensive knowledge of the Colchis area. This is especially true for the elite of Iolkos, who enjoyed great prosperity during the 14th and 13th centuries BC. But if the gold of the Tholos tomb in Kazanaki indeed came from Colchis, is there any evidence to suggest a Mycenaean trade presence in the area?

The reality is that the existence of Mycenaean artifacts and pottery in the Black Sea region is quite limited. However, a few key items have been discovered that suggest a possible Mycenaean presence. These include swords and spearheads found at Georgian sites that bear striking similarities to their Mycenaean counterparts. This could suggest that, while not abundant, there was some degree of Mycenaean presence or influence in the area.

From the Mycenaean Tholos tomb at the site "Kazanaki" of Volos, 1500-1300 BC., Archaeological Museum of Volos, Thessaly, Greece

By MARIA KRITA

Deciphering 'ko-ki-da': The Linear B Conundrum and its Implications for Mycenaean History

The mention of the term "ko-ki-da" in the Linear B texts (specifically tablet Kn Sd 4403) from Knossos, Crete, has sparked intriguing debates among researchers. Some scholars initially proposed that "ko-ki-da" represented an early reference to "Colchida," the Mycenaean Greek term for Colchis. This interpretation was primarily based on phonetic similarities between the two words.

If this interpretation were accurate, it would establish a direct link between the Mycenaean civilization and the distant region of Colchis during the Late Bronze Age, further supporting the historicity behind the myth of the Argonautic Expedition. It would also suggest that the Mycenaeans had an extensive knowledge of the geography of the Black Sea region.

However, this interpretation has been met with considerable skepticism. A significant counterargument is that the context in which "ko-ki-da" appears in the Linear B texts contradicts its identification with Colchis. The texts in question refer to chariot repairs, making it unlikely that "ko-ki-da" would denote a geographical location.

Instead, it has been suggested that "Kokidas" might have been the name of a chariot repairer. This interpretation aligns more closely with the context of the texts and the conventions of Linear B inscriptions, which often include the names of individuals associated with specific tasks or professions. It's worth noting that Linear B was primarily used for administrative records, so mentions of occupations were common.

As with much of the study of ancient languages and scripts, the interpretation of "ko-ki-da" remains a subject of debate. While the prospect of a direct reference to Colchis in the Linear B texts is tantalizing for historians and archaeologists, the evidence, as it currently stands, leans more towards the term denoting an individual involved in chariot repairs rather than the far-off land of the Golden Fleece.

Colchis: The Land of the Golden Fleece and its Historical Significance in the Ancient World

Colchis, known to the ancient Greeks as the land at the edge of the known world, was a significant region located on the south-eastern coastline of the Black Sea. Its territory encompassed the western part of modern-day Georgia and the southern parts of Russia and Turkey. This region was notable for its fertile lands, rich mineral resources, and strategic location on the crossroads between Europe and Asia, making it a key area for trade and cultural exchange.

The earliest reports of Colchis come from Assyrian sources dating back to the reign of Tukulti-Ninurta I, around the 13th century BC. The Assyrians referred to this region as "Kilakku’", a term that denoted the lands to the north of Assyria. Assyrian accounts, such as those from Tukulti-Ninurta I, suggest that Colchis was home to a diverse and heterogeneous population, likely due to its location on major trade routes.

The Urartians, who inhabited the neighboring kingdom of Urartu (approximately corresponding to modern-day Armenia and eastern Turkey), referred to this region as "Qulḫa", as seen in their cuneiform inscriptions (cun. 𒆳𒄣𒌌𒄩). During the 8th century BC, relations between Urartu and Colchis became hostile, leading to a series of military campaigns. The Urartian king Sarduris II, known for his ambitious expansionist policies, led two major campaigns against Colchis, capturing significant portions of its territory. This conflict illustrates the geopolitical importance of Colchis during this period.

Despite these invasions, Colchis retained its distinctive culture and identity. In terms of its cultural heritage, Colchis was known for its unique metallurgical techniques and advanced agricultural practices. Its inhabitants were skilled in the working of gold, silver, and bronze, with many artifacts attesting to their craftsmanship. They also cultivated various crops, including cereals, grapes, and fruits, and were among the first people to cultivate the vine and produce wine.

Colchis would later come under the influence of the Achaemenid Persian Empire and eventually become a part of the Kingdom of Pontus before being incorporated into the Roman Empire as the province of Lazicum. Today, the ancient region of Colchis corresponds primarily to the western part of Georgia, where its rich history and cultural heritage are still evident in the local traditions, archaeological sites, and folklore.

In conclusion, while the Argonautic Expedition is primarily a tale of heroic myth and legend, a careful examination of historical, geographical, and archaeological evidence suggests a possible kernel of truth within this ancient narrative. While the Golden Fleece may not have been a literal object, it could represent the economic wealth derived from the gold-rich sands of the Phasis River and the advanced metallurgical practices of the time.

Archaeological findings, especially those from the Tholos tomb in Kazanaki, provide compelling evidence of a connection between the Mycenaean Greeks and the Colchis region. The alluvial gold used in the manufacture of precious objects found in the tomb is strikingly similar to the gold that would have been collected from the Phasis River. This suggests that the Mycenaeans had not only knowledge of the gold-rich region of Colchis but also likely had some form of interaction or trade with the area.

Furthermore, the few Mycenaean artifacts discovered in the Black Sea region, such as swords and spearheads, point to a limited yet significant presence of the Mycenaeans in the area. It suggests that, despite the scarcity of direct archaeological evidence, there were cultural exchanges and interactions between these two regions during the Bronze Age.

The search for historical truth behind myths like the Argonautic Expedition is not only fascinating but also significantly enriches our understanding of ancient societies. It allows us to appreciate the complexity of their economic systems, their technological capabilities, and their far-reaching trade networks. Moreover, it underscores the value of interdisciplinary research, combining history, archaeology, geography, and literature to unravel the threads of our shared human past.

Ultimately, while we may never fully separate fact from fiction in the story of Jason and the Argonauts, the quest for the Golden Fleece continues to yield golden nuggets of historical and archaeological insight. In this sense, the journey of exploration and discovery encapsulated in the Argonautic Expedition continues today, not on mythical seas aboard the Argo but in the field of research, where every new piece of evidence brings us closer to understanding the intricate tapestry of our ancient past.