Reportage By Sotiris Skouloudis, Newsbomb, Greece

What scholars have long known—that in the Aegean region and the wider Mediterranean people frequently communicated via fire-beacon systems—is well attested, although it has not been emphasized as it should be. With such systems—transmission of messages by fire—the news of Troy’s fall was, after all, relayed swiftly.

What has not been formally archaeologically proven—but informally, all the evidence is present—is that this complex message-transmission system was part of daily life for the Minoans nearly four millennia ago. According to the discovery at Kastelli, this enriches our knowledge of Minoan—and broader Mediterranean—culture.

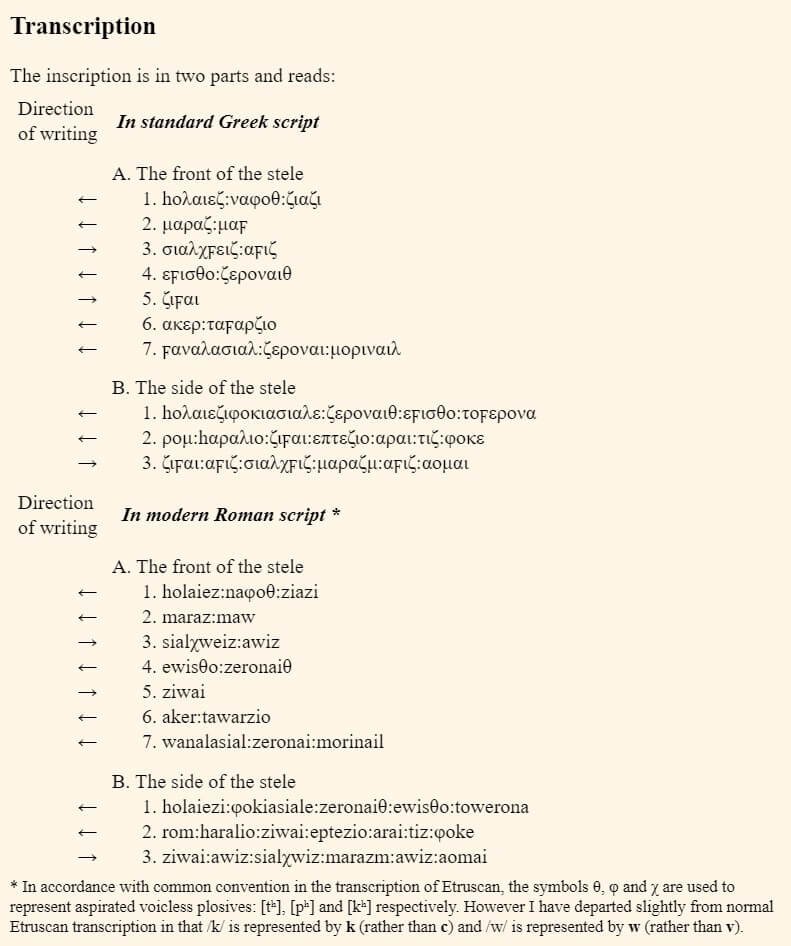

According to published studies by archaeologist Nikos Panagiotakis, who discovered the Minoan beacons known as “Sorous,” this constitutes the oldest known system for sending coded messages by fire ignition. Functioning with light signals, it enabled rapid communication.

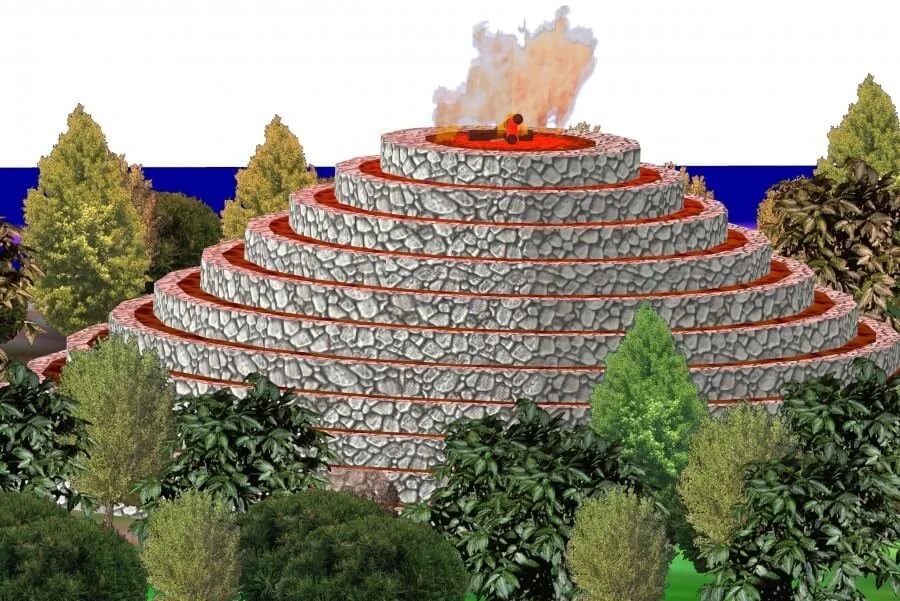

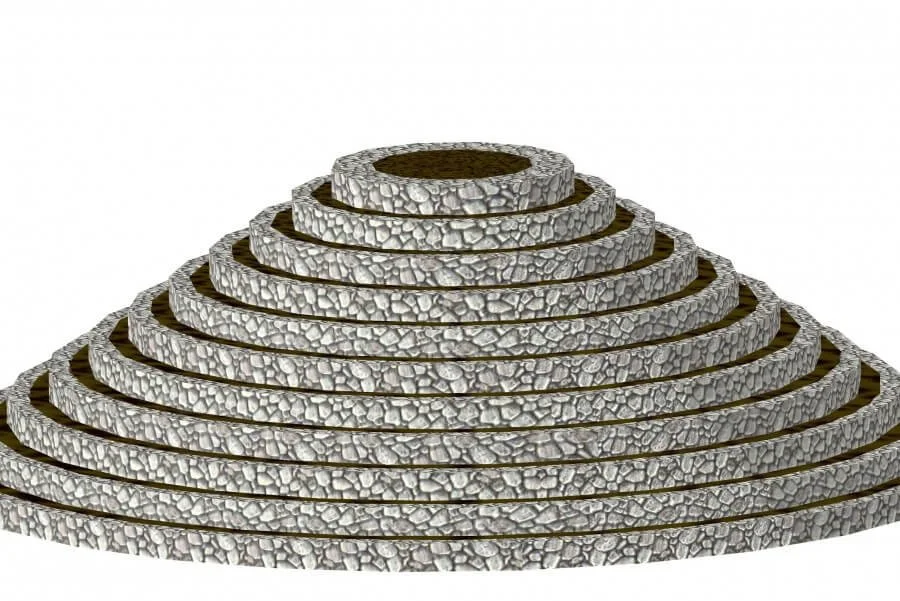

Panagiotakis’s publications at international conferences and years of field research reveal that Minoan Sorous are large truncated-cone structures (made of walls and earth)—in essence, platforms upon which signal fires were kindled. They represent a colossal engineering achievement of the Minoan era—comparable in conception and execution to the Minoan palaces. Their function was both communicative and defensive: enabling Minoan authorities to monitor coasts, roads, and all regions of strategic importance and to relay signals across these points rapidly.

A Network Spanning All of Crete

A large number of beacons likely covered the entirety of Crete, allowing messages to traverse the island—and reach nearby Aegean islands—very quickly. Thus, these beacons ensured communication with surrounding regions and islands, the secure transport of goods, and likely safe navigation.

Panagiotakis’s Lifelong Dedication

Archaeologist Nikos Panagiotakis devoted much of his life to his native region—without institutional funding, he systematically “combbed” the Pedias area of Central Crete, the hinterland of the Minoan palatial cities of Knossos and Malia. Between 1982–1989 and 2001–2009, in an 800 km² area, he identified around 2,500 archaeological sites dating from the Neolithic to Ottoman periods.

Among these were earth-covered hill-like features still called “Sorous.” His surface survey revealed the secret previously hidden for 4,000 years: these 200 or so Sorous are visible across the Pedias plains, detectable by ash and heat-altered soil layers—evidence that fires were regularly lit atop them.

The Nature and Function of the Sorous

The Sorous—named by later locals and still present—are truncated-cone structures built from concentric or semicircular stone walls filled with soil, located on hills or ridges. They range from 5 to 60 meters in diameter and 2 to 8 meters in height. At their tops, red clay soil was placed and fired by rainfall and beacon fires, producing scattered shards of baked clay originating from the uppermost level of the beacon structure. Thus, all Sorous contain abundant pieces of baked clay on their surfaces.

Panagiotakis explains that he gradually recognized the function of these Sorous: as massive visibility constructions on hilltops and ridge-lines marking critical junctions—and smaller structures that demarcated and monitored ancient roads. All Sorous, regardless of size, share the same features: truncated-cone shape, concentric and transverse walls, indicating shared design principles.

These structures enabled fast, safe, and efficient message transmission across both short and long distances—virtually eliminating geographic barriers. They also served defensive and fortification functions, protecting travelers, trade, and transport. The Sorous had direct line-of-sight from the north to the south coast of Crete to relay messages swiftly over great distances.

Satellite Imaging and Hierarchical Network Structure

Collaboration with the Institute for Mediterranean Studies under Professor Apostolos Sarris used satellite imagery to map the complete communication system, the control zones of each beacon, and their interconnections. Analyses demonstrated a dense communication network between Sorous and Minoan settlements, suggesting a hierarchical structure based on their use, location, and control range. Some were larger, others smaller. The largest and best-preserved— the Pantelis Soros—spans over 2.5 acres.

The most important Sorous were positioned along the northern coastline and to the east and west of Panagiotakis’s research area—where immediate warning was vital in case of invasion.

Operational Details: Guards, Infrastructure, and Defense

Panagiotakis describes the system’s operation: palace officials selected hills or elevated sites to light fires. Guards stationed in shifts awaited signals from visually connected elevations. “Installation” meant actual buildings where guards lived, stored food and fuel, and could defend themselves if attacked. The presence of functional pottery and obsidian blades in many Sorous indicates permanent garrisoning. These were likely staffed by military personnel or local reinforcements, operating around the clock. A defensive role is evident in the narrow single entrance found in excavations by the Heraklion Antiquities Authority.

Sorous date from the Early to Late Palace periods (c. 1900–1700 BCE). The Pantelis Soros alone holds approximately 5,500 m³ of earth and stone, marking its construction as a monumental achievement. Most building material came from the local area in abundance.

Why the Conical Shape and Elevated Sites?

Panagiotakis explains: today the hills of the Pedias region are devoid of dense vegetation. He believes the soros’s height was dictated by surrounding tree canopy heights. The structure needed to elevate beacon flames above vegetation, implied by the presence of baked clay. The truncated cone shape also provided structural stability and minimized fire spread—its broad base functioning as a firebreak, with only a small top section exposed for fire.

The Papoura Soros: A Minoan “Radar”?

When asked specifically about the Papoura Soros at Kastelli—the site of the exciting new find—Panagiotakis says: “Excavation by the Heraklion Antiquities Authority revealed a more impressive monument than I had imagined. Its meticulously engineered structure points to palatial authority aimed at controlling territories and roads between the hinterland and palace centers to secure movement of people and goods. Just as Mesopotamian trade stations lined routes, some Sorous may have served as traveler waystations”.

He stresses that monuments should not be studied in isolation but in relation to others of similar type. The Papoura Soros closely resembles the larger Pantelis Soros, both built with concentric walls forming truncated cones. In Papoura, one can now see cross-walls forming a cruciform structure supporting the roof. Above that lay a clay cap—despite damage from German WWII pillboxes, fragments of fired clay remain on the surface. Other Sorous also hosted wartime fortifications.

That modern radar for Kastelli Airport was placed on Papoura underscores the monument’s strategic importance as part of an ancient system of communication and defense—much like modern radar systems.

Continuity and Modern Use: From Antiquity to the Information Age

Remarkably, these elevated sites were reused through successive eras—from Homeric to classical Greece through the Ottoman period, even into modern times. Folk tradition recalls that when a Cretan killed a Turk, he fled to a nearby island (often Kasos). Islanders received messages via beacon fires starting from the Toplou Monastery bell tower in Lasithi—and then dispatched boats to retrieve the fugitive.

In our time, the Papoura Soros was selected for radar placement. During the Cold War, large telecom radar installations at the Ederi Soros destroyed parts of the mound. Today, many Sorous host telecommunications antennas for major mobile carriers—continuing their legacy as high-visibility signal points.

Discovering the Minoan beacon-Sorous system in the 21st century—an era heralded as the Information Age—is particularly meaningful.

Open Questions and the Future of Research

Key questions remain: Were these systems exclusive to Minoans on Crete, or did similar constructions exist throughout the Aegean world? The Minoans had relations with northern neighbors and Aegean islanders. Geophysical analysis on a mound near Volos, mainland Greece, found signs of similar ground burning. Panagiotakis believes research should expand from Crete to the wider Greek area.

What remains to be officially confirmed—if the archaeological services of Crete and the Greek Ministry of Culture choose to seriously engage with these findings—is that the brilliant monument at Papoura Kastelli is just one of many Sorous in Minoan Crete within a complex telecommunication network. If validated, Papoura Soros could trigger the protection, promotion, and display of all Minoan beacon-Sorous across Crete as integral components of a monumental Minoan infrastructure. They should be safeguarded under archaeological law as discoveries of major significance.