Where does the name "Asia" come from, mentioned in the Mycenaean texts? What are the Anatolian contributions to Mycenaean Greek religion? How did the name of an entire continent arise from an epithet of a deity?

Asia, a vast continent with innumerable cultural, linguistic, and topographical features, draws its name from a seemingly unassuming ancient epithet. The name 'Asia,' as it is understood in its present usage, has its roots in the Mycenaean age, the era preceding classical Greece by several centuries. The term ‘Aswiya,’ derived from Hittite and Luwian languages, emerges as a significant name within the Mycenaean administrative archives, leading historians to trace its transformative journey from being a simple toponym to the name of the largest continent.

The Mycenaean Epithet 'Aswiya' and its Origin

On Mycenaean tablets, a large number of deities are mentioned, frequently in relation to the dedication of sacrifices and objects. While some of these gods are uniquely Mycenaean, others date back to the first millennium BC.

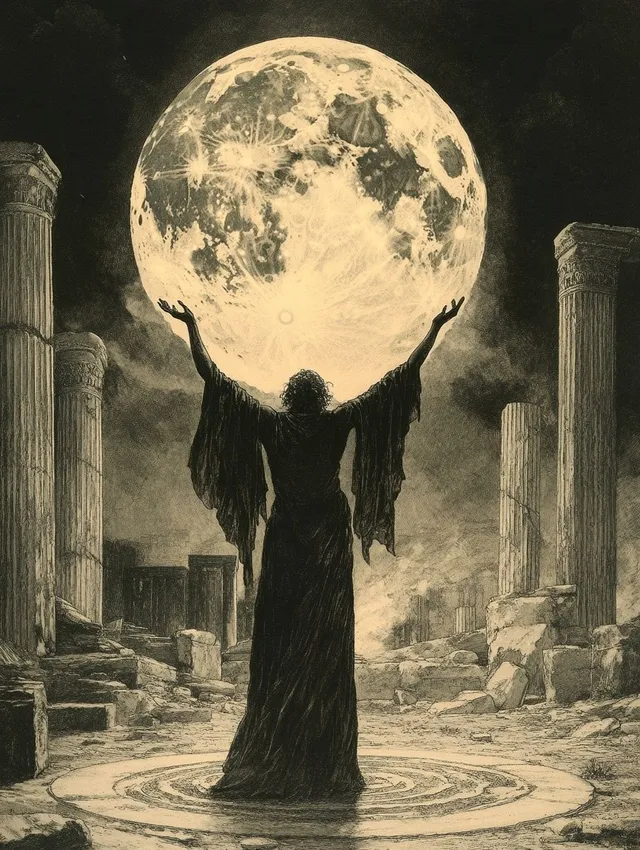

"Potnia," one of the most popular Mycenaean theonyms, undoubtedly refers to a number of female deities who are the Great Mother's offspring. Potnia daburinthoyo (lady of the labyrinth), Potnia aswija (lady of Asia), Sitopotnia (lady of grain), and Potnia hikkweia are the result (lady of horses).

Kwerasia (Therasia) and Thehia Mater (Divine Mother or Mother of the gods) must both fall under the same religious category. Kwerasia (Therasia) must be associated with Potnia of beasts (the woman of wild creatures).

The term 'Aswiya,' as found in the Mycenaean records, is closely associated with the Hittite and Luwian term 'Asuwa,' which denoted a confederation of states in western Anatolia during the late Bronze Age. This epithet was documented in a series of tablets discovered in the Mycenaean palatial archives, such as those in Pylos and Knossos. The tablets provide a glimpse into the intricate diplomatic relationships, trading networks, and power dynamics between these ancient civilizations.

The original geographical designation of 'Aswiya' or 'Asuwa' is believed to have been relatively limited, referring primarily to regions on the Aegean Sea's eastern coasts and western Anatolia. The term's precise location remains a subject of scholarly debate, but it is generally agreed that it centered around the Troad and extended southward along the Aegean coastline.

A specific offering of perfumed oil to a "Potnia Aswiya" (Asian Heavenly Lady/Despoina) is mentioned on a tablet at Pylos (Fr 1206). This is significant not only because it refers to the Anatolian toponym Aswiya or Assuwa but also because of the enormous quantity of oil offered—150 liters, according to estimates.

Evidence of a religious syncretism shared between the Mycenaean world and the Anatolian East

Mycenae: Ivory sculptural group of child with two kneeling females wearing flounced skirts. 15th c. BC, Athens, National Archaeological Museum, 3" high

The term is most likely to refer to "Asia" rather than the Greek location "Assos," making this Potnia one with an overtly foreign, in fact "Asian," name. This adjectival title is one of only two for Potnia (with i-qe-ja). Additionally, this word may have a predecessor in Linear A, which is close in date to the related word's earliest occurrences in Hittite annals.

The epigraphic, scribal, and archaeological details of the tablet that refer to an "Asian deity" strongly support the idea that it is of foreign origin. The tablets that were discovered in Room 38 rather than Room 23 (behind the megaron), where the majority of the oil jars and tablets were kept or discovered, provide information on Potnia Aswiya and her offerings.

In the major repository for the distribution of perfumed oil to Poseidon at Pakijana, the Dipsioi, etc., this distinguishes Aswiya from deities more common at Pylos. This puts her in close proximity to Ma-te-re te-i-ja, or "Divine Mother," another foreign deity, if not the Mother of the Gods.

Her fascinating title alludes to a distant ancestor of the Meter Theion that was brought from Anatolia to classical Greece. She is reported in Fr 1202a from the same chamber (38), with a comparable high amount of oil (sage-scented) and a similar emphatic quantity as her "Asian" sister.

As a single month or festival (me-tu-wo ne-wo) is designated for ma-te-re te-i-ja, this huge sum, which dwarfs all other gifts or allotments to deities in the same set of tablets, cannot be some sort of annual assessment. The identical hand, the sole scribe present in both the Room 23 and the Room 38 records, and obviously a pro in the perfume business, further connects these two exotic goddesses.

So, the two goddesses are united by the findspot, accountant, large amounts of oil, and the foreign, if not Anatolian, links of their names, which distinguish them from other gods named for oil distribution at Pylos, whose records were discovered in Room 23.

Where exactly was the Assuwa region?

A region in western Anatolia (Asia Minor) is referred to as Assuwa in Hittite writings. Most famously, it was employed as a political name to denote the "Assuwan Confederacy," which was founded by 22 states to oppose the Hittite ruler Tudhaliya I or II.

It is thought that Aswiya or Assuwa is where the Greek word Asia originated. Some have claimed that this is evidence of an offering made to a foreign deity who had a site of worship in Messenia, possibly in conjunction with the Aswiyan women who are currently employed by Pylos. This is further asserted to be proof of religious syncretism between Pylos and the East in the form of "transported deities.”

Assuwa has frequently only been identified by modern scholars as existing in the northwest corner of Anatolia, in a region centered to the north or north-west of the future Arzawa. As a result, it has become difficult to include Caria, Lukka, and/or Lycia because these regions are obviously in south-western Anatolia. By including them, Assuwa would have encompassed regions to the north and south of Arzawa. Yet, it's possible that the Assuwa confederative organization had states in two or more geographically distinct regions without a shared land border.

The "Asian meadow" that Homer alludes to, a plain in Lydia, must also be implied by the word "Asia." Later, the word came to mean "Asia Minor" and "continent Asia."

The Transformation of 'Aswiya' into 'Asia'

The evolution of the term 'Aswiya' into 'Asia' is a testament to the dynamic interplay of language, geography, and history. Over centuries, as civilizations rose and fell, the term 'Asia' began to be used by the Greeks in a broader context than its original Mycenaean designation. The Ionian Greeks, residing in the western part of Asia Minor, were among the first to use 'Asia' to describe the lands to their east, initially referring to the areas ruled by the Persian Empire.

The Achaemenid Persians themselves seem to have adopted a version of the term, using "” to refer to the province that roughly corresponds to modern-day Turkey. This Perso-Greek usage of 'Asia' became increasingly prevalent throughout the Hellenistic period, especially after Alexander the Great's conquests, which spread Greek culture and language far and wide.

From the Greeks to the Romans

As the torch of empire passed from the Greeks to the Romans, so too did the term 'Asia.' The Romans initially used 'Asia' to denote the province of Asia Minor, their first acquisition in Anatolia, conquered in the 2nd century BC. This Roman province of 'Asia' comprised most of western Anatolia and was one of the wealthiest and most densely populated regions in the empire.

Locator map of the Asia province in the Roman Empire (125). Milenioscuro - Own work

However, as the Roman Empire expanded eastward, incorporating vast territories spanning three continents, the term 'Asia' began to be applied to an increasingly large geographical area. By the time of the late Roman Empire, 'Asia' had become a catch-all term for the lands to the east of the Roman world, encapsulating the enormity and diversity of the continent that we now know as Asia.

The Transition from the Romans to the Modern Western World

The term 'Asia,' as we understand it today, continued to evolve well after the fall of the Roman Empire, owing much to the advancements in geographical knowledge and global exploration in the subsequent centuries. During the Middle Ages, European explorers and cartographers began using 'Asia' to refer to the vast lands east of the Ural Mountains, the Caucasus, the Caspian Sea, and the Black Sea, reflecting a more modern understanding of continental boundaries. As the Age of Discovery dawned in the 15th century, propelled by advancements in navigation and seafaring, 'Asia' started encapsulating regions even further east, including the Indian subcontinent, the Far East, and the islands of the Pacific. This continental understanding was eventually formalized in the Western tradition through the works of influential scholars and geographers, such as Ptolemy and later, Mercator. The once Mycenaean toponym, 'Aswiya” has thus journeyed across millennia through the lenses of Greeks, Persians, Romans, and countless others before being adopted by the modern Western world to represent an incredibly diverse continent rich in culture, history, and natural splendor.

The story of 'Aswiya' and its evolution into 'Asia' is a fascinating journey through time, mirroring the ebb and flow of empires, the transference of cultural influence, and the transformation of geographical understanding. It demonstrates the enduring power of names and their ability to encapsulate complex historical narratives within a few letters. From a simple Mycenaean epithet referring to a region in western Anatolia, 'Asia' has evolved to designate the largest and most diverse continent on Earth, home to more than half of the world's population.