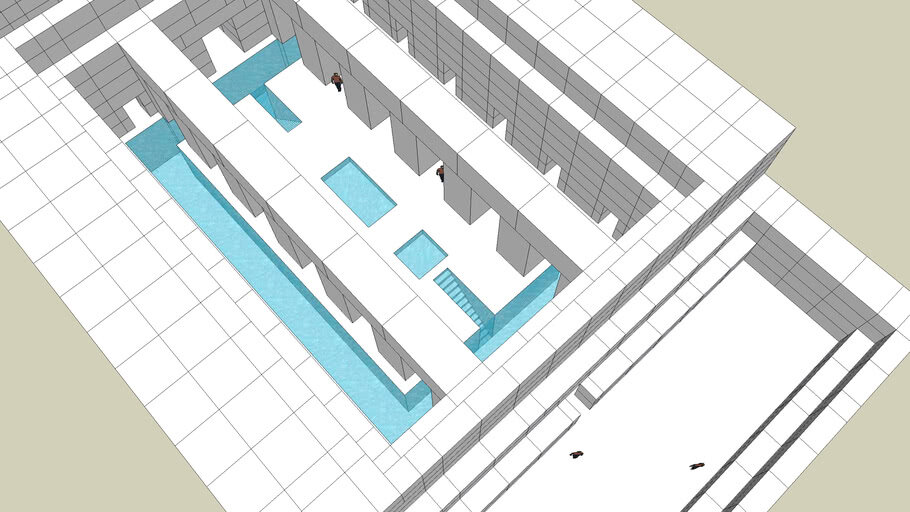

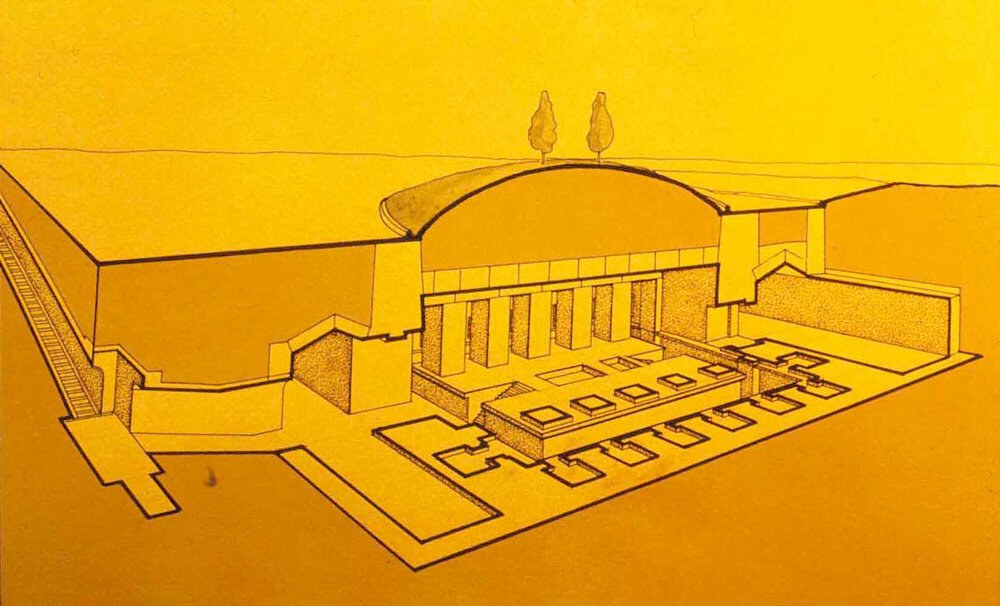

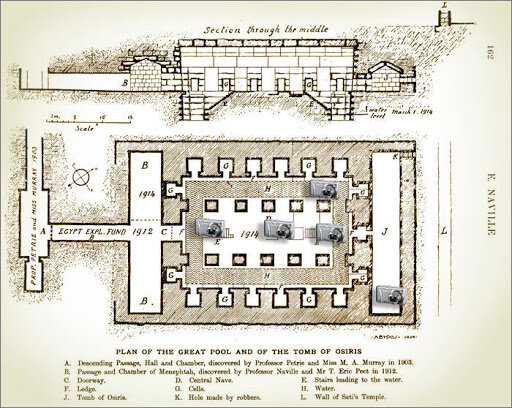

Standing on a promontory at a bend in the Nile, where in ancient times sacred crocodiles basked in the sun on the riverbank, is the Temple of Kom Ombo, one of the Nile Valley's most beautifully sited temples. Unique in Egypt, it is dedicated to two gods; the local crocodile god Sobek, and Haroeris (from har-wer), meaning Horus the Elder.

Temple in Kom Ombo - Sachin Vijayan Photography/Getty Images

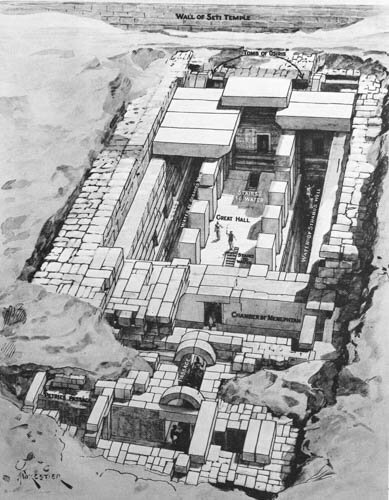

The temple's twin dedication is reflected in its plan: perfectly symmetrical along the main axis of the temple, there are twin entrances, two linked hypostyle halls with carvings of the two gods on either side, and twin sanctuaries. It is assumed that there were also two priesthoods. The left (western) side of the temple was dedicated to the god Haroeris, and the right (eastern) half to Sobek.

Reused blocks suggest an earlier temple from the Middle Kingdom period, but the main temple was built by Ptolemy VI Philometor, and most of its decoration was completed by Cleopatra VII’s father, Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos. The temple’s spectacular riverside setting has resulted in the erosion of some of its partly Roman forecourt and outer sections, but much of the complex has survived and is very similar in layout to the Ptolemaic temples of Edfu and Dendara, albeit smaller.

Touring the Temple

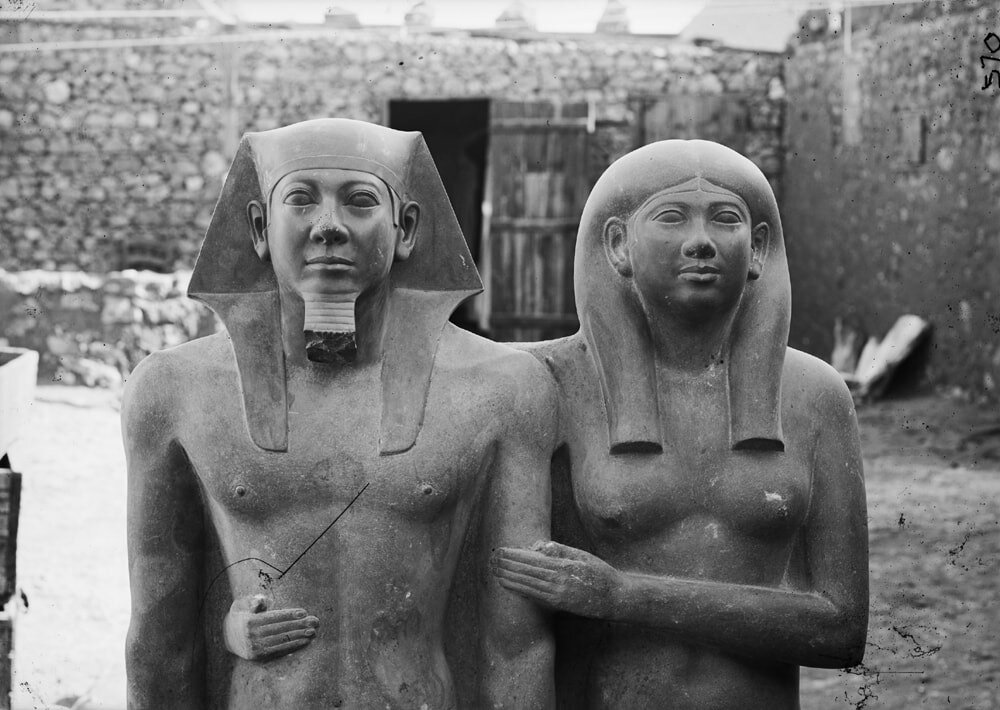

Passing into the temple’s forecourt, where reliefs are divided between the two gods, there is a double altar in the centre of the court for both gods. Beyond are the shared inner and outer hypostyle halls, each with 10 columns. Inside the outer hypostyle hall, to the left is a finely executed relief showing Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos being presented to Haroeris by Isis and the lion-headed goddess Raettawy, with Thoth looking on. The walls to the right show the crowning of Ptolemy XII by Nekhbet (the vulture-goddess worshipped at the Upper Egyptian town of Al Kab) and Wadjet (the snake-goddess based at Buto in Lower Egypt) with the dual crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, symbolising the unification of Egypt.

Reliefs in the inner hypostyle hall show Haroeris presenting Ptolemy VIII Euergetes with a curved weapon, representing the sword of victory. Behind Ptolemy is his sister-wife and coruler Cleopatra II.

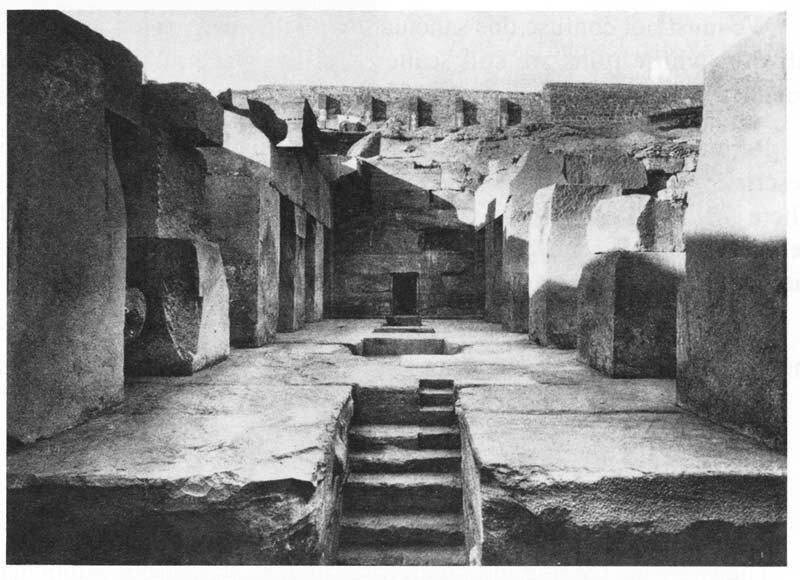

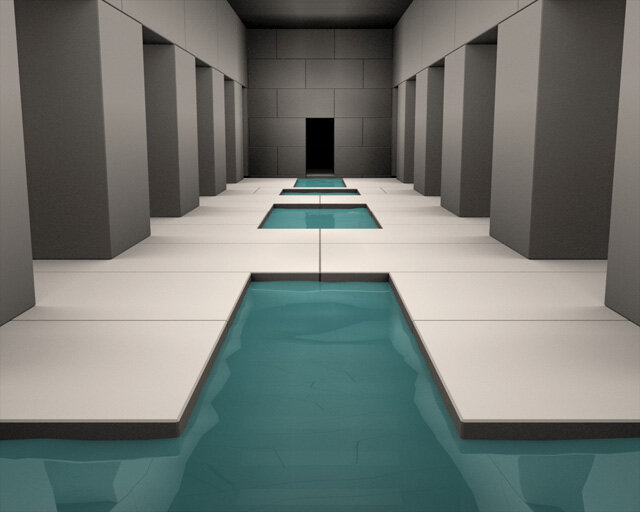

From here, three antechambers, each with double entrances, lead to the sanctuaries of Sobek and Haroeris. The now-ruined chambers on either side would have been used to store priests’ vestments and liturgical papyri. The walls of the sanctuaries are now one or two courses high, allowing you to see the secret passage that enabled the priests to give the gods a ‘voice’ to answer the petitions of pilgrims.

The outer passage, which runs around the temple walls, is unusual. Here, on the left-hand (northern) corner of the temple’s back wall, is a puzzling scene, which is often described as a collection of ‘surgical instruments’. It seems more probable that these were some of the accoutrements used during the temple’s daily rituals, although the temple was certainly a place of healing, the nearest thing to an ancient hospital.

Near the Ptolemaic gateway on the southeast corner of the complex is a small shrine to Hathor, while a small mammisi (birth house) stands in the southwest corner. Beyond this to the north you will find the deep well that supplied the temple with water, and close by is a small pool in which crocodiles, Sobek’s sacred animal, were raised.

Mummified Crocodiles at Kom Ombo

The path out of the complex leads to the new Crocodile Museum. It's well worth a visit for its beautiful collection of mummified crocodiles and ancient carvings, which is well lit and well explained. The museum is also dark and air-conditioned, which can be a blessing on a hot day.