The answer to the age-old topic of when the first creatures appeared on Earth has been eluding naturalists since Charles Darwin's time thanks to a study led by the University of Oxford. In the journal Trends in Ecology & Evolution, the findings were just recently published.

Reconstruction of the Ediacaran seafloor from the Nama Group, Namibia, showing early animal diversity. Credit: Oxford University Museum of Natural History / Mighty Fossils

Around 574 million years ago, the earliest fossilized animal remains were discovered. They appear as a sudden 'explosion' in Cambrian-era rocks (539 million to 485 million years ago), which seems to go against the generally slow rate of evolution. However, they are unable to explain why the earliest animals are absent from the fossil record. Many scientists, including Darwin himself, think that the earliest animals actually originated far before the Cambrian period.

In the early Neoproterozoic era (1,000 million years ago to 539 million years ago), according to the "molecular clock" technique, animals likely first appeared 800 million years ago. The time period when two or more living species last had a common ancestor can be ascertained using this method, which uses the rates at which genes accumulate mutations. Animal fossils have not been discovered, despite the fact that early Neoproterozoic rocks contain fossilized microbes like bacteria and protists.

Reconstruction of Charnia, a candidate for the first animal fossil from the Ediacaran Period as old as 574 million years ago. Credit: Oxford University Museum of Natural History / Mighty Fossils

Paleontologists were left with a conundrum: Does the molecular clock method overstate the time of animal origin? Or did animals exist in the early Neoproterozoic but were too soft and delicate to survive?

For this investigation, a group of scientists under the direction of Dr. Ross Anderson from the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Oxford performed the most extensive evaluation to date of the preservation conditions that would be anticipated to catch the earliest animal fossils.

Lead author Dr. Ross Anderson said: “The first animals presumably lacked mineral-based shells or skeletons, and would have required exceptional conditions to be fossilized. But certain Cambrian mudstone deposits demonstrate exceptional preservation, even of soft and fragile animal tissues. We reasoned that if these conditions, known as Burgess Shale-Type (BST) preservation, also occurred in Neoproterozoic rocks, then a lack of fossils would suggest a real absence of animals at that time.”

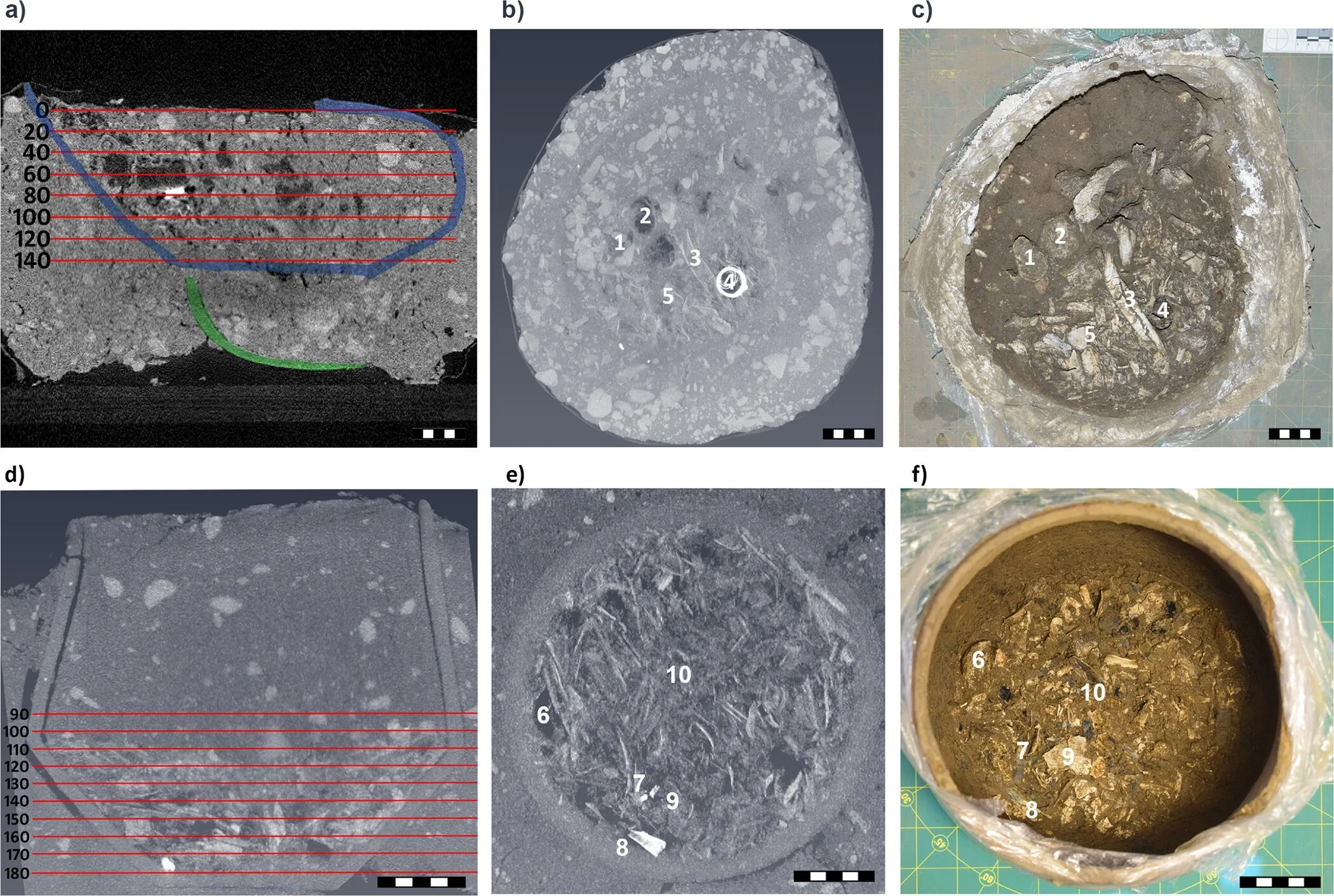

The research team compared the Cambrian mudstone deposits from almost 20 locations that preserved just mineral-based remnants (such as trilobites) with those that preserved BST fossils in order to better understand this. These techniques included infrared spectroscopy performed at Diamond Light Source, the UK's national synchrotron, as well as energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction at the Departments of Earth Sciences and Materials at the University of Oxford.

According to the research, berthierine, an antibacterial clay, was notably concentrated in fossils with outstanding BST-type preservation. Around 90% of samples that contained at least 20% berthierine produced BST fossils.

Dickinsonia, one of the oldest animal fossils from the Ediacara Biota, Ediacaran Rawnsley Quartzite Formation, Australia. 560–550 million years old. Credit: Lidya Tarhan

An further antibacterial clay known as kaolinite appears to actively bond to decomposing tissues at an early stage, producing a protective halo during fossilization, according to microscale mineral mapping of BST fossils.

“The presence of these clays was the main predictor of whether rocks would harbor BST fossils” added Dr. Anderson. “This suggests that the clay particles act as an antibacterial barrier that prevents bacteria and other microorganisms from breaking down organic materials.”

The materials were then analyzed using these methods using a variety of fossil-rich Neoproterozoic mudstone layers. According to the research, the majority lacked the components required for BST preservation. However, three deposits in Canada's Nunavut, Russia's Siberia, and Norway's Svalbard exhibited compositions that were nearly identical to BST-rocks from the Cambrian era. The conditions were probably suitable for the preservation of animal fossils, however none of the samples from these three strata included any.

“Similarities in the distribution of clays with fossils in these exceptional Cambrian deposits and rare early Neoproterozoic samples suggest that, in both cases, clays were attached to decaying tissues and that conditions favorable to BST preservation were available in both time periods,” Dr. Anderson continued. Contrary to certain molecular clock estimations, this is the first “evidence for absence” and supports the idea that animals had not developed by the early Neoproterozoic epoch.

Image of one of the Tonian sites with BST preservation but no animal fossils from fieldwork. Svanbergfjellet Formation, De Geerbukta, Svalbard, Norway. Credit: Ross Anderson / University of Oxford

The study, in the opinion of the experts, points to the Svalbard formation's youngest estimated age of 789 million years as the earliest feasible age for the beginning of animals. The team will now look for deposits in the Neoproterozoic that are increasingly younger and have the right circumstances for BST preservation. By doing so, it will be possible to determine the age of rocks where creatures are missing from the fossil record for reasons other than the fact that they couldn't have been preserved as fossils. Additionally, they plan to conduct laboratory tests to look at the processes behind clay-organic interactions in BST preservation.

Dr. Anderson continued, “We are now able to understand the nature of the remarkable fossil record in a way that we have never been able to accomplish before by mapping the compositions of these rocks at the microscale. In the end, this might help us understand how the fossil record may be skewed towards retaining particular species and tissues, changing how we perceive biodiversity throughout various geological eras.”