Archaeologists in northern Albania have uncovered a large Roman chamber tomb dating to the 3rd–4th century AD—the first monument of its kind ever documented in the country. The structure, discovered at Strikçan near Bulqiza in the historic Dibra region, measures roughly 9 by 6 meters with a burial chamber about 2.4 meters high. Its slabs bear inscriptions in Greek letters, including a rare bilingual dedication naming the deceased Gellianos and invoking Jupiter.

How the Discovery Happened

The find began with villagers who noticed unusually cut stones on a plateau. Acting on these reports, a team from Albania’s Institute of Archaeology opened test trenches in early August and soon identified a substantial underground construction sealed with massive limestone blocks. The excavation is directed in the field by Erikson Nikolli, who has provided the principal on-site statements to the press.

Architecture and Construction

The tomb is built from large, carefully dressed limestone slabs forming a stepped descent into a rectangular antechamber and inner chamber. At approximately 9 × 6 meters (29 × 19 ft) with a chamber height of ~2.4 m (8 ft), the monument is unusually spacious for the region and is being discussed by the team as a chamber tomb approaching the scale of a small mausoleum. Its plan and size distinguish it sharply from the simpler cist and pit graves more typical of northern Albania.

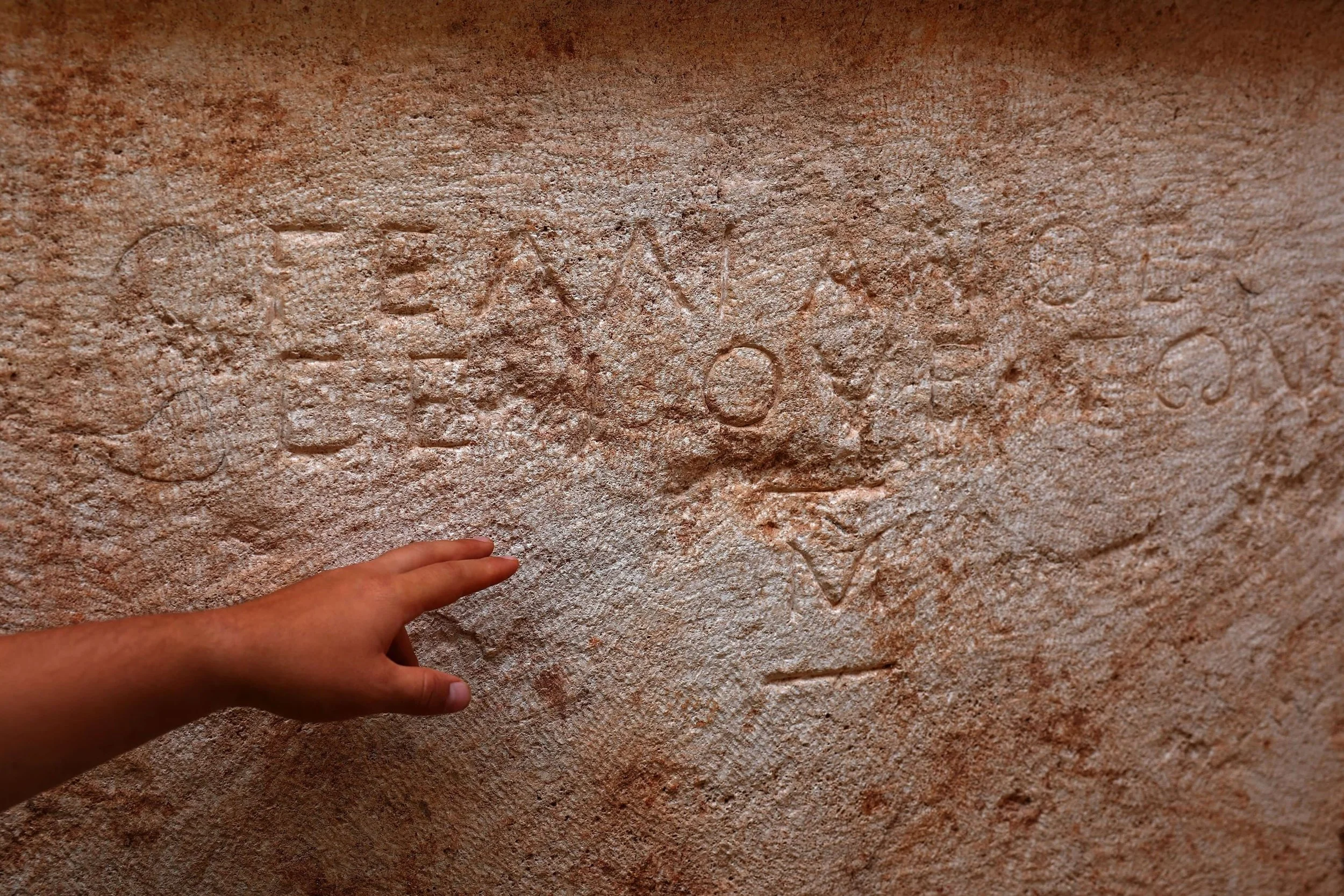

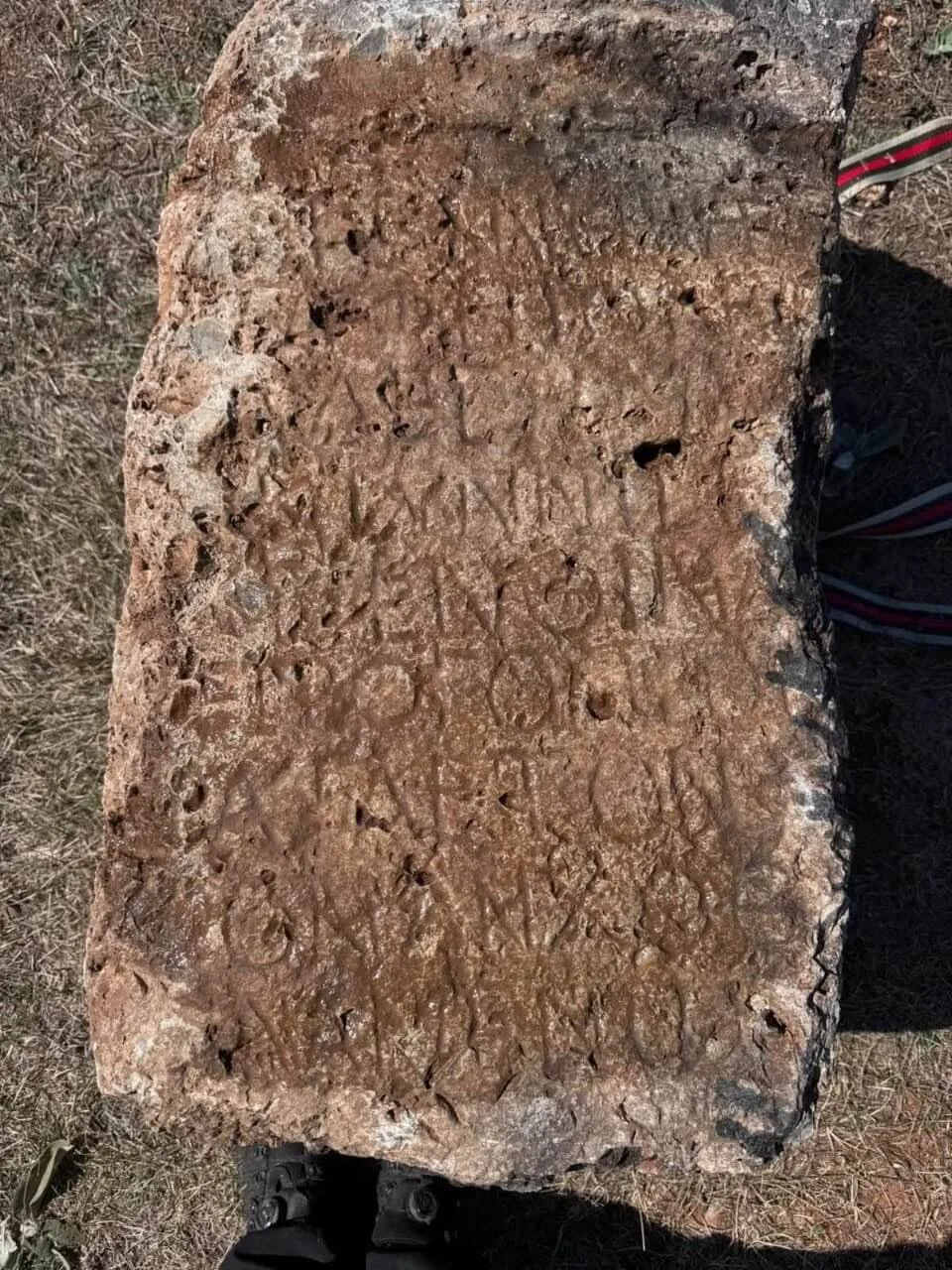

The Bilingual Inscription

Among the most significant features is an inscription cut in Greek letters that records the name Gellianos (Gellianus) and includes a dedication to Jupiter (Ζεύς/Ιουπίτερ). Officials have characterized it as a bilingual text (Greek and Latin), a rare phenomenon in Albania and the first ever recorded in the Dibra region. The surviving lines indicate both a personal memorial formula and a votive dedication, underscoring how Roman religious vocabulary could be framed in Greek epigraphic practice on the empire’s eastern Adriatic fringe. Full epigraphic publication is pending; additional inscribed stones recovered nearby may relate to a second monument.

Who Was Buried Here?

While osteological analysis and laboratory work remain to be reported, the scale, masonry quality, and decorated components point to a high-status burial—very likely a wealthy local notable with Roman citizenship or strong ties to the provincial elite. Nikolli has indicated that the chamber likely held two individuals, conceivably family members, with the named principal being Gellianos. The blend of Greek epigraphy, Latin theonym, and Roman funerary form reflects the cultural hybridity expected in a borderland community integrated into imperial networks.

Finds Inside the Tomb

Despite evidence that the tomb suffered at least two episodes of looting—one in antiquity and a later disturbance involving machinery—the team recovered noteworthy materials that survived the intrusions. These include fragments of textiles embroidered with gold thread, glass plates, and metal knives. Gold-thread fabric in particular is a strong status marker across the late Roman world, often associated with garments worn by elites at death. The fact that fragile objects like thin glass and textiles were preserved at all speaks to the tomb’s robust construction and stable microenvironment.

Why the Inscription Matters

The bilingual dedication is crucial for understanding language practice and identity in Roman Albania. Greek remained a dominant public epigraphic medium across the eastern Adriatic, but the invocation of Jupiter (rather than, say, Zeus alone) sits squarely within the Roman civic-religious idiom, suggesting self-presentation that was at once local and imperial. Officials emphasize that Dibra has yielded very few Roman-period inscriptions of any kind, and none with this bilingual profile, making the Strikçan text a reference point for future studies of provincial religion and onomastics in the region.

Comparanda and Rarity

Reports consistently describe the Strikçan monument as the first monumental Roman tomb documented in Albania. Other celebrated burials in the country—like the Illyrian royal tombs at Selcë e Poshtme—are earlier (Hellenistic) and architecturally different. For the Roman period proper, chamber tombs of this scale have not previously been recorded in Albanian archaeology, which explains the strong reaction from national authorities and the immediate plans for protection and presentation.

Public Presentation and Next Steps

The discovery quickly drew public attention. Albania’s culture ministry and the prime minister’s office circulated photographs and video from the site, while state broadcasters and international outlets amplified the news. Authorities intend to stabilize and conserve the structure and develop the location for controlled visitation, citing both heritage stewardship and cultural tourism. Meanwhile, the field team continues inscriptional analysis and artifact conservation, steps that will culminate in a technical report and, eventually, a peer-reviewed publication.

Interpreting Strikçan in Its Historical Landscape

Strikçan sits on a plateau that commands routes linking the Drin valley to passes toward North Macedonia. In late antiquity, such corridors knit together hinterland communities with coastal nodes on the Adriatic and Ionian seas, facilitating the flow of goods, people, and ideas. The tomb’s Roman funerary architecture combined with a Greek-lettered, Jupiter-focused text embodies this connective provinciality: the deceased (Gellianos) memorialized in a language legible across the eastern Mediterranean, yet inscribed with the central god of Rome’s public cult. This is precisely the kind of hybrid epigraphic habit scholars expect in regions where Latin power overlapped with long-standing Hellenic literacy.

What We Still Don’t Know

Key questions remain open pending analysis:

Text reconstruction. Only short excerpts have been released; a squeeze or high-resolution RTI record will be needed to establish the full lineation, letter heights, and restorations. (Officials have noted additional stones with writing from a nearby, possibly related monument.)

Burial practice. Whether the bodies were placed in sarcophagi, on biers, or in loculi is not yet reported. The chamber’s size and internal articulation may clarify this once excavation drawings are published.

Precise dating. The 3rd–4th-century window is based on architecture and finds; radiocarbon, textile analysis, and glass typology could narrow it.

Significance

For Albania, the Strikçan chamber is both a landmark discovery and a missing puzzle piece. It demonstrates that monumental Roman funerary architecture did reach the country’s northeastern uplands, and it provides a datable, inscribed context linking local elites to imperial religious vocabulary. For the wider Balkans, it offers a new datapoint for the diffusion of Roman mortuary forms into Greek-literate zones. And for epigraphy, it adds a rare bilingual text from a region where such inscriptions are sparse, enabling finer-grained discussion of language choice, identity, and ritual in provincial communities.