The topic of homosexuality in ancient Greece has long fascinated historians and scholars, prompting extensive debate and research. The societal norms and legal frameworks of the time are crucial to this discussion, particularly those that Solon, a significant Athenian statesman and legislator, put in place. His laws, often interpreted as a reflection of societal attitudes toward homosexuality, provide a valuable lens for understanding ancient Greek social ethics and legal standards.

Solon, renowned for his comprehensive reforms in Athens during the archaic period, aimed to address political, economic, and moral decline. His legislations not only sought to stabilize Athenian society but also to shape the moral fabric of the city-state. Among the various issues addressed through his laws, the treatment of homosexual practices stands out as particularly severe, suggesting a complex relationship between societal norms and personal behaviors.

It is crucial to distinguish between the modern understanding of homosexuality and the ancient Greek concept of same-sex relations. In ancient texts, the term often translated as "homosexuality" does not necessarily align with contemporary interpretations. The Greek word "paiderastia," often misconstrued in the west as indicative of homosexual activities between an adult man and a boy, more accurately refers to a form of mentorship and education, albeit with an erotic component. This relationship, structured through social norms, was distinct from the perceptions attached to "kinaidos," a term used pejoratively for men who assumed a passive sexual role, which was viewed with disdain and associated with shame.

According to the interpretation of Solon’s laws, engaging in homosexual acts could lead to severe penalties, including the loss of crucial civic rights. The prohibitions included being barred from serving on the council of nine, participating in elections, advocating for citizens, wielding power within or outside Athens, serving as a wartime emissary, expressing public opinions, entering sacred temples, participating in athletic competitions, and frequenting the agora. Violation of these laws was not only punishable by social ostracization but potentially by death.

However, the severity of these laws and their enforcement might not fully encapsulate the nuanced views of homosexuality in ancient Greek society. While Solon's legislation appears harsh, it is important to remember that legal codes often serve not only as reflections of current practices but as tools for promoting desired behaviors and discouraging others. The presence of these laws suggests a concern for the regulation of social order and the preservation of traditional values, particularly in public life.

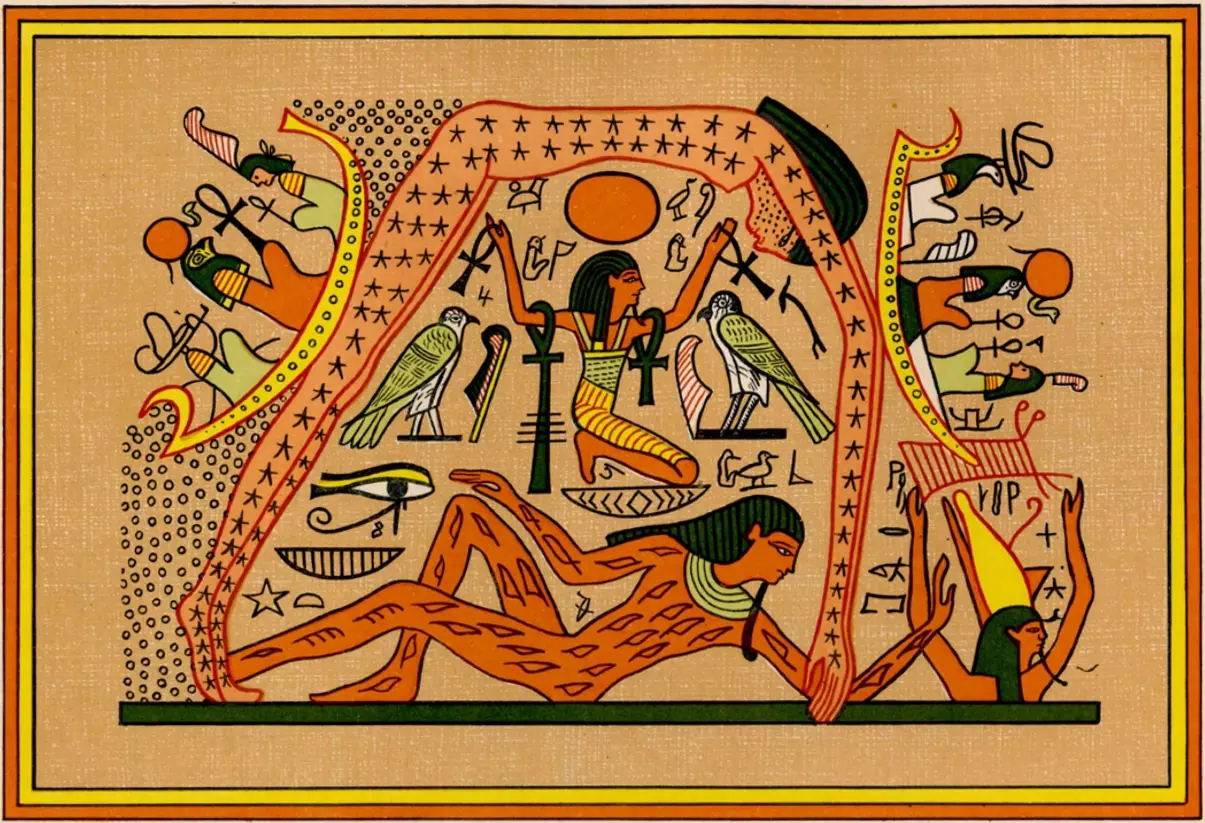

Moreover, the artistic expressions from the same period, such as vases depicting homoerotic scenes, indicate that same-sex relationships, at least in some forms, were part of cultural representations and possibly more accepted in less formal contexts. This juxtaposition of legal strictures against a backdrop of cultural artifacts suggests a society grappling with complex attitudes towards sexuality.

In conclusion, the interpretation of Solon’s laws as purely anti-homosexual oversimplifies the historical context and ignores the multifaceted nature of ancient Greek social norms. While these laws undoubtedly imposed strict penalties on certain homosexual behaviors, their existence and enforcement reflect broader concerns about social order and moral conduct rather than a wholesale condemnation of homosexuality. This complexity invites a deeper examination of how legal, social, and cultural elements intertwined to shape the ancient Athenian attitude toward diverse sexual practices.