The Maya were exceptional astronomers and developed advanced calendars to track time.

The ancient Maya civilization is shrouded in mystery, yet it remains a benchmark for numerous significant achievements in mathematics, architecture, and astronomical knowledge.

Before the Spanish conquest of Mexico, the Maya had developed the most brilliant civilization in the Western Hemisphere. They practiced agriculture, were formidable warriors, built imposing pyramids and temples, and had knowledge of the concept of the number zero.

In addition, they worked with copper and gold, knew the art of weaving, and used a form of hieroglyphic writing. The roots of the Maya civilization date back to prehistoric times, beyond 2000 BC, corresponding to the Archaic period.

The Maya continue to impress and remain a subject of study for archaeologists and historians to this day.

Here are 7 things you may not know about the ancient Latin American civilization.

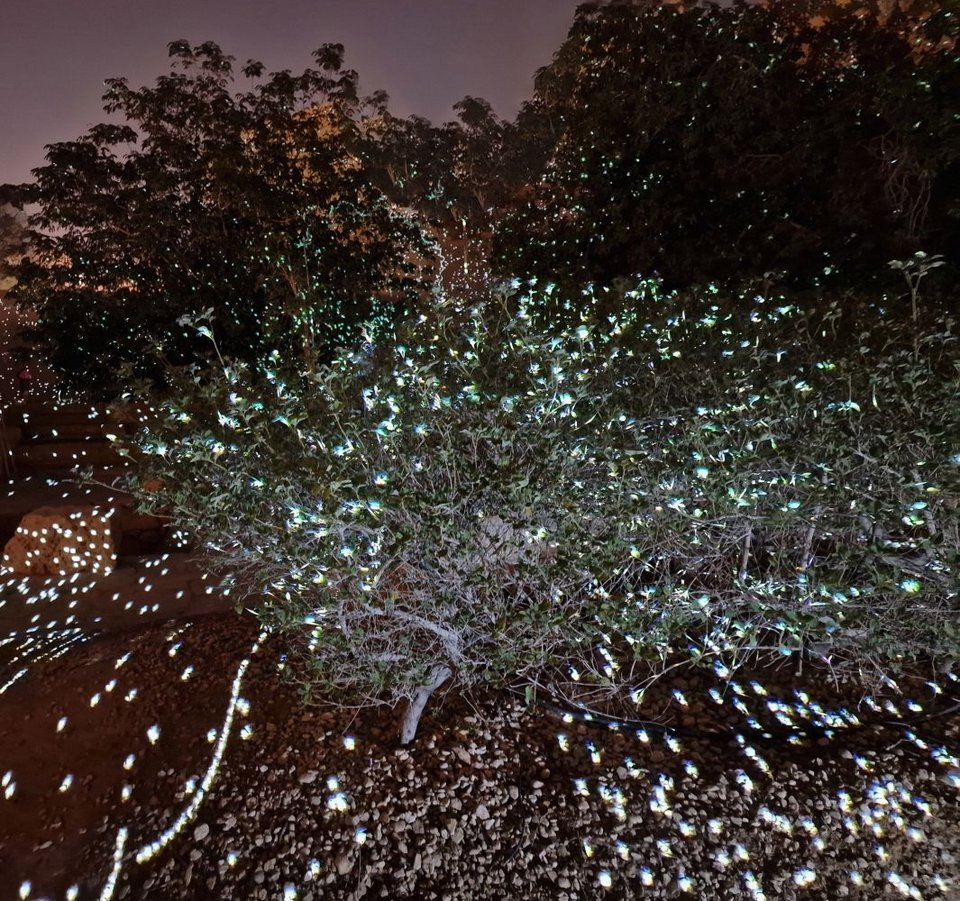

1. They Were Exceptional Astronomers

The Maya were exceptional astronomers and developed advanced calendars for tracking time. They had a cyclical perception of time and believed that at the end of each pictun cycle (about 7,885 years), the world would be destroyed and recreated. This belief caused confusion thirteen years ago when some incorrectly interpreted the Maya calendar, claiming that the world would end on December 21, 2012.

However, scientists pointed out that the calendar used by the ancient civilization did not predict the end of the world—it simply marked the end of one cycle and the beginning of another. The Maya also used the Tzolkin calendar (260 days) and the Haab calendar (365 days, divided into 18 months of 20 days and one month of 5 days), which allowed them to predict solar and lunar eclipses with great accuracy. The Maya often determined dates by using both calendars together. Dates in this form would only repeat every 52 solar years.

2. Their Complex Writing System

The Maya developed one of the most complex writing systems of the ancient world, using a form of hieroglyphic writing. For centuries, scientists struggled to decipher it, as it combined symbols representing entire words and syllables.

In the mid-20th century, Russian linguist Yuri Knorozov and other researchers managed to understand their distinctive writing system. Today, scientists can read most of the surviving Maya texts, revealing details about their history, religion, and daily life.

3. They Used Zero in Mathematics

The concept of zero was unknown to most ancient civilizations, but the Maya had invented a special symbol for zero, resembling a shell. Their numerical system was based on the vigesimal system (base 20). Thanks to this innovation, they were able to perform complex calculations, primarily for astronomical and calendrical purposes.

4. They Were Made Up of Independent City-States

Unlike other great civilizations like the Aztecs and Incas, the Maya did not have a single state with a central ruler. Instead, they were made up of independent city-states, such as Tikal, located in the tropical forest of northern Guatemala, Palenque (formerly known as Lacamha), and Copán, in western Honduras.

Each city had its own king (known as Kʼuhul ajaw), who was considered a "divine leader" and ruled with the help of nobles and priests.

5. They Practiced Painful Infant Skull Modifications

The Maya regarded elongated skulls as a symbol of beauty and prestige. To achieve this, they placed special wooden frames on infants' heads, pressing their skulls to give them an elongated shape. This practice was particularly common among the upper social classes and likely had religious significance, as the Maya associated elongated skulls with the forms of their gods.

6. Most Cities Were Abandoned Before the Spanish Conquest

Although the Spanish conquest contributed to the collapse of the Maya civilization, many of their great cities had already been abandoned centuries earlier. The reasons for the decline of the cities (around 800-1000 AD) remain uncertain, but scientists speculate that it was due to a mix of political and environmental factors (such as drought, climate change, and internal conflicts).

However, the Maya civilization never fully disappeared. Most modern Maya live in Guatemala, Belize, and the western parts of Honduras and El Salvador, as well as large sections of the Mexican states of Yucatán, Campeche, Quintana Roo, Tabasco, and Chiapas.

7. They Played a Ball Game Without Using Their Hands

The Maya played a complex ball game (known as pok-ta-pok or pitz) in large arenas. Players could use all parts of their bodies (elbows, shoulders) but not their hands to bounce a heavy rubber ball (estimated to weigh 4 kg), trying to pass it through a stone ring positioned vertically on the sides of the arena.

The game had religious and political dimensions, and in some cases, the losers might have been sacrificed to the gods.

The Maya civilization continues to intrigue and educate, leaving behind remarkable achievements that still captivate us today.