What radiocarbon dating revealed, according to the research director at the Demokritos National Center for Scientific Research

A long-held belief about one of ancient Greece’s most significant archaeological discoveries has now been called into question. A new scientific study argues that the skeleton found in one of the royal tombs at Vergina does not belong to Philip II of Macedon, the father of Alexander the Great, as previously thought.

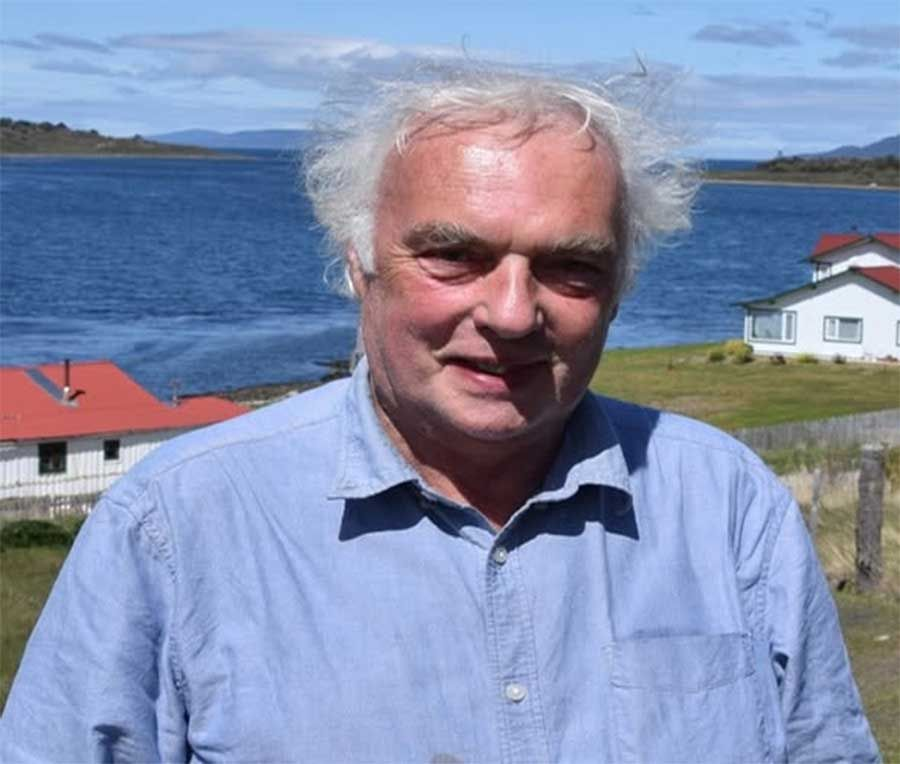

The findings come from a recent study led by Dr. Giannis Maniatis, Director of Research at the Laboratory of Archaeometry at Greece’s National Center for Scientific Research “Demokritos.” Using advanced radiocarbon dating methods, his team concluded that the remains found in Tomb I at the Great Tumulus of Vergina date to between 388 and 356 BCE—decades before Philip II’s known death in 336 BCE.

This revision significantly challenges past claims. Ever since the discovery of the vast burial complex at Vergina—believed to be the royal necropolis of the ancient Macedonian capital Aigai—archaeologists have debated the identities of the remains in the tombs known as Tombs I, II, and III. These had been tentatively linked to Alexander’s half-brother Philip III Arrhidaeus, his son Alexander IV, and his father, Philip II himself. The actual tomb of Alexander the Great remains unknown.

Last year, a team led by Professor Antonios Bartsiokas of the Democritus University of Thrace claimed to have finally settled the debate, asserting that the remains in the tombs definitively belonged to Alexander’s family—Philip II among them.

But Dr. Maniatis’s new study presents compelling counterevidence. Not only does the radiocarbon dating preclude the possibility that the male remains belong to Philip II, but analysis also revealed that the man died between the ages of 25 and 35—considerably younger than Philip, who was around 45 years old when assassinated.

Another major blow to the previous identification is the discovery of infant bones in the tomb. Contrary to earlier assumptions that these belonged to a single child (possibly Philip’s and Cleopatra’s infant), the new study found remains from at least six different infants.

Even more striking: these infant remains date to the Roman period (150–130 BCE)—more than 200 years after the adult’s death. Researchers believe Roman-era parents may have buried their deceased infants in the preexisting tomb through an opening left by Celtic tomb raiders in the 3rd century BCE. That opening remained accessible well into Roman times.

In light of this new evidence, Dr. Maniatis and his colleagues conclude that the previous theory—linking the remains in Tomb I to Philip II, his wife Cleopatra, and their infant—is no longer scientifically tenable.

The true final resting place of Philip II of Macedon, the man who laid the groundwork for Alexander the Great’s empire, remains a mystery.