In the rugged terrain of West Texas, a remarkable find is rewriting what we know about the prehistoric inhabitants of the region.

Deep within the San Esteban Rockshelter cave system, researchers uncovered exceptionally well-preserved hunting equipment that dates back approximately 6,500 years.

This discovery is being hailed as one of the oldest intact weapon systems ever found in North America.

The excavation was led by a team from the Big Bend National Park Research Center (CBBS), in collaboration with the University of Kansas's Odyssey Archaeological Research Center.

For years, it was believed that ancient hunter-gatherer societies in the area primarily used hunting tools with spearpoints. However, the discovery of this complete and intact set of gear allows scientists to move from theoretical assumptions to a detailed reconstruction of early technological tools.

Indigenous Hunting Tools

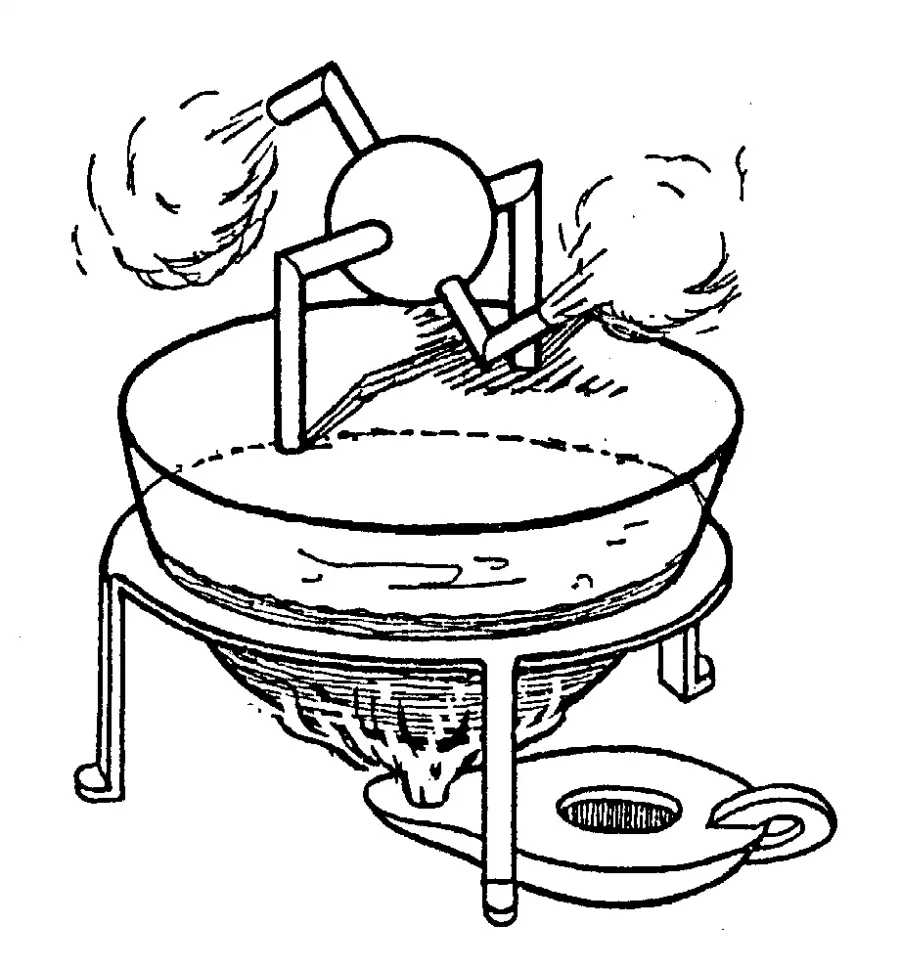

Among the most significant artifacts recovered were six spearpoints made of stone, used to attach arrows to a lever for throwing spears.

Also found were four axes made from deciduous wood, possibly used for applying poison, next to four worn-out arrowheads, and a rare boomerang.

Another discovery included half of a lever with its handle, worn down by time.

Devin Pettigrew, a weapons specialist and associate professor at the Big Bend National Park Research Center, noted, "We haven't found the side handle of the lever, but we know enough about this particular type to reconstruct its original form."

The preservation of these ancient Native American hunting tools is exceptional, especially considering their age.

Most archaeological finds from this period are fragmentary, making full reconstructions difficult.

Reconstructing the Original Gear

Thanks to this discovery, researchers were able to piece together nearly the entire weapon system, allowing them to imagine how the components functioned in real hunting scenarios.

Beyond the weaponry, the shelter provides fascinating insights into the lives of the people who once inhabited the region.

Archaeologists uncovered a folded, processed antelope hide that still retained its original fur, along with human feces—evidence that enriches the human context of the find.

The hide, which had holes scattered along its edges, suggests it was stretched over a frame to soften it, reflecting techniques known from the traditions of Plains Indigenous people.

The moment of discovery remains unforgettable for the excavation team. "We sat there, staring in awe at the find. It happens once in a lifetime," Pettigrew describes.

"It looks like someone folded the hide we found over the rock and left it untouched for 6,000 years."

The arrangement of broken arrowheads and the careful deposition of weapon parts suggest the shelter may have had symbolic or spiritual significance.

"These interpretations, which are based on more recent cultures, become more challenging the further back we go in time," Pettigrew notes.

The possibility that the set was purely utilitarian adds a deeper layer to our understanding of prehistoric lifestyles.

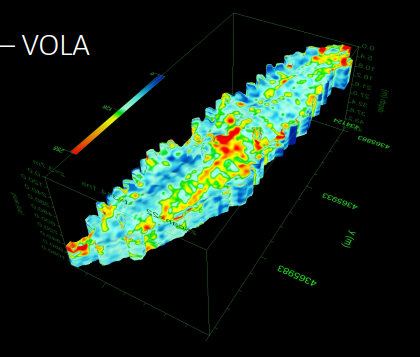

Precision and Power Weapons

Louie Bond, a researcher at Texas Parks and Wildlife magazine, explains the technical aspects of the artifacts:

"The arrowheads fit with the levers. When thrown, they follow a straight line, and the points of the axes fit into notches at the end of the main shaft."

This construction gave ancient hunters greater strength and accuracy, maximizing their chances of success in the harsh environment of ancient Texas.

These technical insights deepen our understanding of prehistoric engineering and highlight the interaction of early societies with their ecosystem—tracking, targeting, and hunting large game with complex, reusable weapons.

Bryon Schroeder, director of the Big Bend National Park Research Center, describes the find as "monumental," stressing how it fills gaps in archaeological knowledge.

"We see great snapshots of their life, sketches of their way of living, their environment, and their interaction with it," he said.

The meticulous excavation, with each artifact coming to light piece by piece, generated excitement with every new discovery.

What initially appeared to be simply the equipment of a hunter is now viewed as a window into an entire way of life shaped by innovation, adaptation, and perhaps even ritual.

As the research team continues to study the shelter, it’s expected that this discovery will continue to influence archaeological studies in North America for years to come.