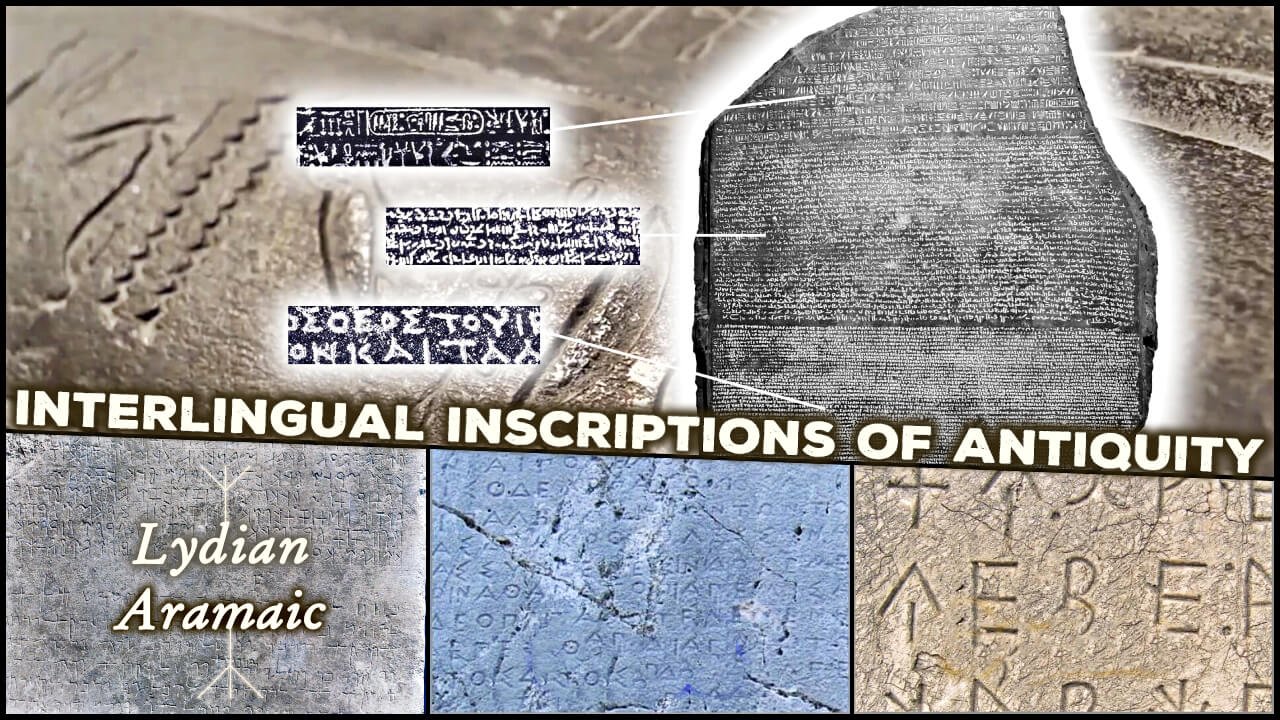

Interlingual inscriptions—texts inscribed in multiple languages—stand as testaments to ancient multilingualism, offering unparalleled insights into cross-cultural interactions and providing scholars with the keys to unlocking long-forgotten languages.

contents

The Rosetta Stone

The Letoon Trilingual Stele

The Xanthian Obelisk

The Behistun Inscription

The Galle Trilingual Inscription

The Canopus Decree (Canopus Stone)

The Sardis Bilingual Inscription

King Ezana’s Stone

The Meroitic scripts of the Kingdom of Kush

The Pyrgi Tablets

The Bilingual Inscription of Kulamanu from Karatepe

The Idalion Bilingual

Societies have flourished and interacted throughout history, leaving behind artifacts, buildings, and inscriptions that serve as reminders of their past. Interlingual inscriptions, or texts written in multiple languages, are among the most remarkable of these. They have been used by researchers to interpret extinct languages in addition to serving as proof of ancient multilingualism. Let's examine some of the oldest and most well-known multilingual inscriptions.

1. The Rosetta Stone

Unearthed near Rosetta (Rashid) in the Nile Delta region of Egypt in 1799, the Rosetta Stone is undoubtedly one of the most famous archaeological discoveries. This granodiorite slab boasts inscriptions in three scripts: Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, Demotic script, and Ancient Greek. With the known Ancient Greek as a reference, scholars, most notably Jean-François Champollion, were able to decipher the hieroglyphs in 1822, unraveling the mysteries of ancient Egyptian writing.

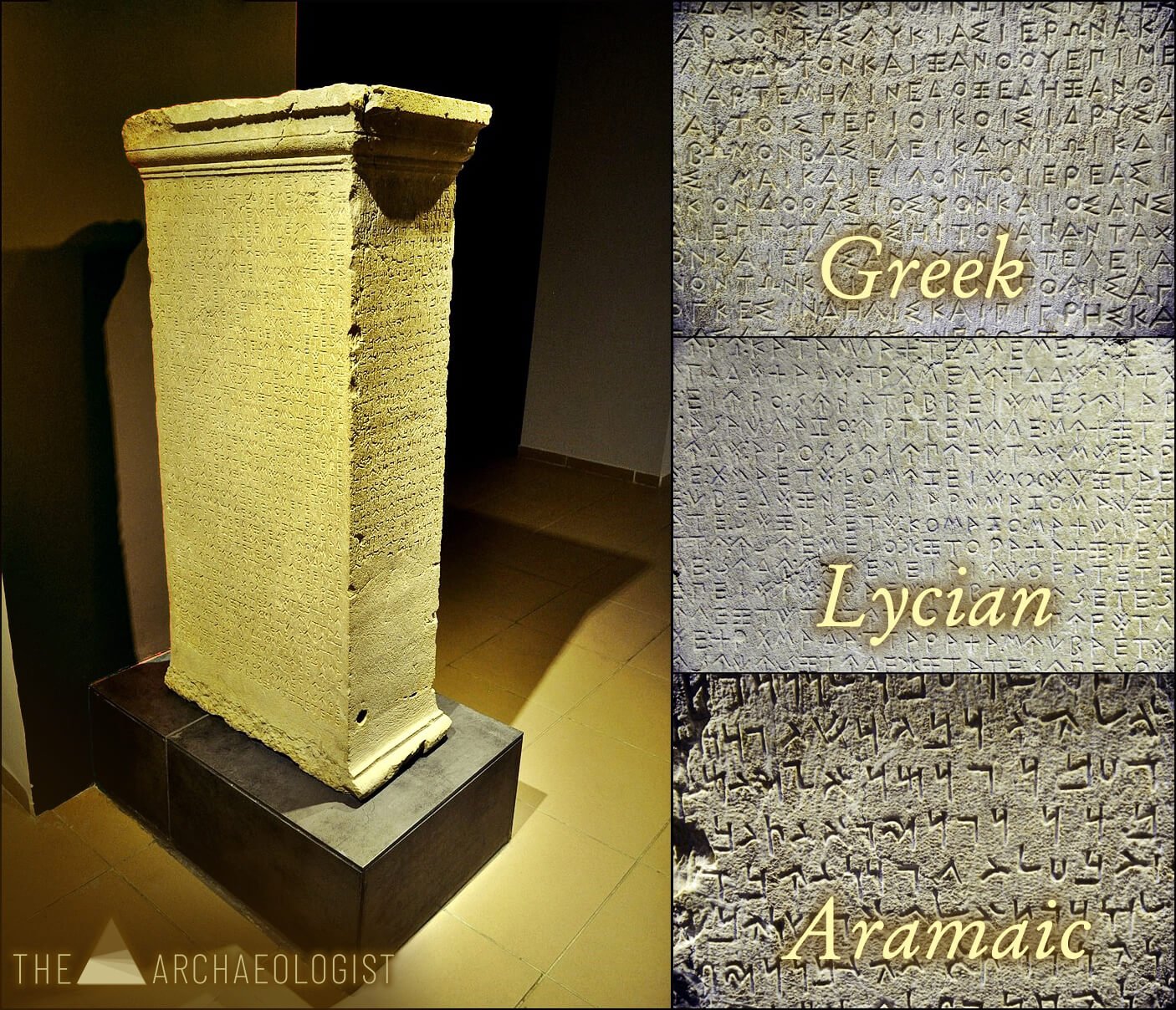

2. The Letoon Trilingual Stele

Located at the Letoon Sanctuary near the ancient city of Xanthos in present-day Turkey, the Letoon Trilingual Stele offers inscriptions in three different languages: Ancient Greek, Lycian, and Aramaic. Dating back to the 4th century BC, this inscription primarily commemorates the achievements of a local prince named Arbinas. The stele has provided scholars with crucial clues for deciphering the Lycian language.

3. The Xanthian Obelisk

Also found in the vicinity of Xanthos, the Xanthian Obelisk, or Xanthos Stele, is a tower-like monument from the 5th century BC with inscriptions in both Greek and Lycian. While less famous than the Letoon Trilingual, the obelisk was instrumental in understanding Lycian B, a variant of the Lycian language.

4. The Behistun Multilingual Inscription

A remarkable example of an ancient interlingual inscription is the Behistun Inscription, situated in modern-day Iran. Originating from the era of Darius the Great in the 5th century BC, the inscription is monumental not only in its physical presence, carved dramatically into a cliff face, but also in its linguistic significance.

The Bisotun Inscription presents texts in three different cuneiform script languages: Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian (a version of Akkadian). It delineates the victories of Darius the Great against the usurper Gaumāta and subsequent revolts, projecting Darius as a divinely appointed king.

The trilingual nature of the inscription was essential in deciphering cuneiform, specifically through the efforts of British army officer Sir Henry Rawlinson in the 19th century. By comparing the three parallel texts, scholars unlocked the secrets of cuneiform scripts, unleashing a deeper understanding of the various civilizations that used them. The Bisotun Inscription thus offers a vivid illustration of the pivotal role of multilingual texts in historical and linguistic research.

5. The Galle Trilingual Inscription

Erected in 1411 in Sri Lanka by the Chinese explorer Zheng He, the Galle Trilingual Inscription contains texts in three languages: Chinese, Tamil, and Persian. It commemorates the offerings made by Zheng He to a Buddhist temple and stands as an enduring testament to ancient maritime routes and cultural exchanges.

The inscription begins with invocations to Buddhist, Hindu, and Islamic deities, reflecting the religious diversity and harmonious coexistence of multiple faiths. It exemplifies the syncretism in religious and cultural practices in both the places Zheng He visited and perhaps in his own crew, illustrating the interconnectedness of ancient civilizations.

The trilingual inscription reflects the maritime prowess of the Ming Dynasty and its diplomatic interactions with various countries. Zheng He's voyages are crucial events that mark the historical silk and spice routes, highlighting the vibrant maritime trade and cultural exchanges that took place across the Indian Ocean.

6. The Canopus Decree (Canopus Stone)

Similar to the Rosetta Stone, the Canopus Decree is a stele that dates back to 238 BC. Found in the ancient Egyptian city of Canopus, the inscription features texts in both hieroglyphic and Greek. The decree praises Ptolemy III for his deeds and establishes a new cult in his honor.

7. The Sardis Bilingual Inscription

The Sardis Bilingual Inscription, dating back to the 4th century BC, is a pivotal artifact in deciphering the ancient Lydian language, similar to the role the Rosetta Stone played for Egyptian hieroglyphs. Lydian was an extinct language spoken in Lydia, modern-day Turkey, during the 1st millennium BC. The inscription, discovered in 1912 in the ancient capital of Lydia, Sardis, consists of texts in both Lydian and Aramaic languages, providing a basis for comparative analysis and eventually leading to the understanding of Lydian.

Enno Littmann was one of the pioneers in decoding the Lydian language. This discovery has had a profound impact on historical linguistics, shedding light on the socio-cultural and historical context of ancient Lydia and emphasizing the importance of bilingual inscriptions in reconstructing lost languages. The Sardis bilingual inscription serves as a bridge to the past, allowing contemporary scholars to connect with the ancient Lydians through their language and history.

8. King Ezana's Stone

King Ezana's Stone, erected in the ancient city of Axum, Ethiopia, during the 4th century CE, remains a pivotal discovery in understanding the complex matrix of language, power, and religion in the region during this era. This artifact is fascinating due to its tri-lingual nature, featuring inscriptions in Ge’ez, Sabaean, and Greek.

Ezana was the ruler of the Kingdom of Aksum, a significant trading empire that spanned territories in present-day Ethiopia and Eritrea. His reign marked a transformative period in the region’s history, notably adopting Christianity as the state religion. King Ezana’s Stone reflects this epochal shift through its inscriptions, offering a royal proclamation that underscores the ruler’s might and his newfound Christian faith.

Each of the three languages on the stone provided a means of communicating with different audiences. Greek was a lingua franca of sorts across many regions due to the prior influence of the Hellenistic world. Sabaean was included due to Axum's interactions and connections with the Sabaean kingdom across the Red Sea, and Ge’ez, being the local language, represented the language of the Axumite people.

Thus, King Ezana's Stone not only offers insights into the Axumite Kingdom’s linguistic milieu but also illustrates the potent intertwining of political power and religious conversion. Additionally, it acts as a bridge connecting different civilizations through language, providing modern scholars with a tangible link to understanding the dynamics of ancient Northeast Africa and its interactions with surrounding regions. Consequently, it is a priceless artifact in the realms of linguistics, history, and the study of early Christianization in Africa.

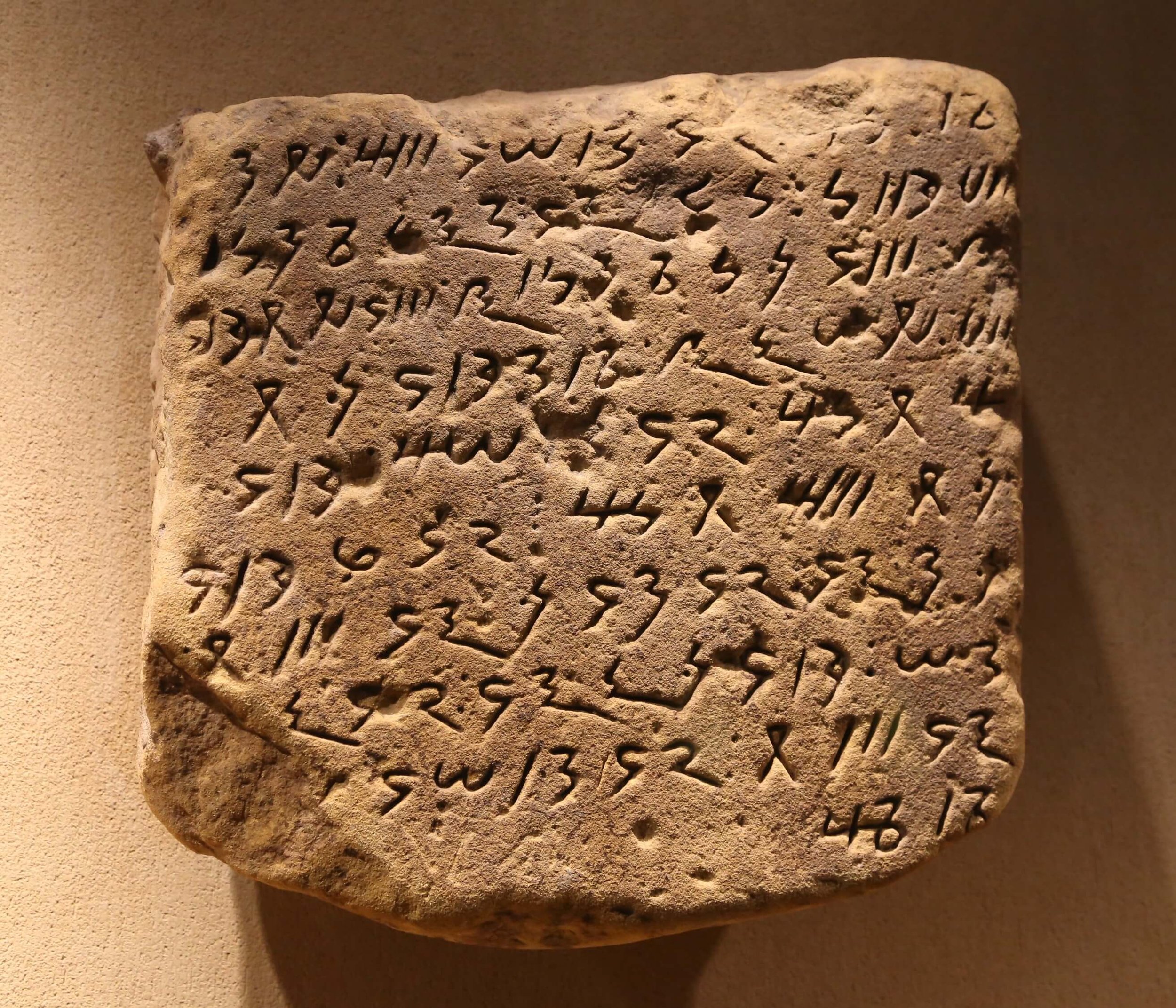

9. The Meroitic scripts of the Kingdom of Kush

While there was not a single inscription, the ancient African Kingdom of Kush (modern-day Sudan) used a script known as Meroitic, which appeared in both cursive and hieroglyphic forms. Occasionally, Egyptian hieroglyphs appeared alongside Meroitic texts, revealing the cultural and linguistic exchanges between ancient Egypt and Kush.

10. The Pyrgi Tablets

Discovered in the ancient Etruscan port of Pyrgi (modern Italy) in 1964, these gold leaf inscriptions from the 5th century BC provide parallel texts in Etruscan and Phoenician. They record the dedication of a temple by Thefarie Velianas, the ruler of Caere, to the Phoenician goddess Astarte.

11. The Bilingual Inscription of Kulamanu from Karatepe

Phoenician part of the inscription / photo Klaus-Peter Simon on Wikimedia Commons

This inscription, from the late 8th century BC, was discovered at the Hittite fortress of Karatepe in Turkey. It provides texts in Phoenician and Luwian hieroglyphics, celebrating the achievements of the local ruler, Azatiwada. It is known as KAI 26 and has served archaeologists as a Rosetta stone for deciphering Luwian glyphs.

12. The Idalion Bilingual

The Idalion Bilingual is a significant archaeological artifact currently housed in the British Museum. It was discovered in Cyprus and played a crucial role in deciphering the Cypriot syllabary, an ancient script used from the 11th to the 4th centuries BC. This bilingual inscription contains the same text in both the well-known Phoenician alphabet and the previously undeciphered Cypriot syllabary. It provides a parallel text in Phoenician and Greek, offering an essential resource for historians and linguists seeking to comprehend the linguistic and political landscapes of ancient Cyprus.

The discovery of the Idalion Bilingual allowed scholars to decode the Cypriot syllabary by comparing corresponding words and phrases in both scripts. This breakthrough had profound implications, shedding light on ancient Cypriot history, culture, and language. It provided insights into religious practices, administrative systems, economic activities, and the linguistic evolution of the region. The Idalion Bilingual serves as a testament to the power of archaeology in unraveling the mysteries of the past and underscores the interconnectedness of human societies.

Legacy of Linguistic Bridges: The Timeless Significance of Interlingual Inscriptions

The abundance of multilingual inscriptions that have been found all across the world indicates how cosmopolitan the ancient world was. They are essential to our comprehension of linguistic evolution and historic diplomatic ties, and they emphasize the importance of cultural and linguistic interaction across civilizations. By spanning languages and civilizations, these inscriptions shed light on the universal human experience throughout time and space.

references

The Rosetta Stone

"The Rosetta Stone," by E.A. Wallis Budge, 1989

The Letoon Trilingual Stele

"Lycia: History, Monuments, and Inscriptions," by G. E. Bean, 1968

The Xanthian Obelisk

"The Lycians in Literary and Epigraphic Sources," by M. Z. Çalışkan, 1988

The Behistun Inscription

"The Behistun Inscription of Darius the Great: Babylonian Version," by L. W. King, R. C. Thompson, 1907

"Darius I and the Persian Empire," by Hywel Clifford, 2016

The Galle Trilingual Inscription

"Zheng He's Maritime Voyages (1405–1433) and China's Relations with the Indian Ocean World: A Multilingual Bibliography," by Roderich Ptak, 2014

The Canopus Decree (Canopus Stone)

"The Decree of Canopus: In Hieroglyphics and Greek, with Translations and an explanation of the hieroglyphical Characters," by S. Birch, 1866

"Ptolemaic Egypt," by Jean Bingen, 2007

The Sardis Bilingual Inscription

"Aramaic Inscriptions and Documents of the Roman Period," By Joseph Naveh (2003)

King Ezana’s Stone

"Ancient Ethiopia," by David W. Phillipson (2009)

The Meroitic scripts of the Kingdom of Kush

"Meroe City: An Ancient African Capital," by P. L. Shinnie, 1996

The Pyrgi Tablets

"The Etruscan Language: An Introduction," by Giuliano and Larissa Bonfante, 2002

The Bilingual Inscription of Kulamanu from Karatepe

"The Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscriptions of the Iron Age," by Annick Payne, 2012.