Proto-Sinaitic Inscriptions and the Name of Moses: A Reexamination of New Archaeological Claims

Recent claims concerning a set of ancient inscriptions discovered in Egypt's Sinai Peninsula have drawn significant attention in the fields of epigraphy, archaeology, and biblical studies. These inscriptions, carved in the Proto-Sinaitic script and dating to the Middle Kingdom period of ancient Egypt (circa 1800 BCE), have been interpreted by independent epigrapher Michael S. Bar-Ron as potentially containing the earliest known reference to the biblical figure of Moses.

The inscriptions in question were found at the Serabit el-Khadim turquoise mines, a remote and historically significant mining complex in the southern Sinai. The site was active during the reign of Pharaoh Amenemhat III and served as both a mining operation and a religious center dedicated to the Egyptian goddess Hathor. Numerous Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions have been documented at the site since the early 20th century, when Flinders Petrie and his team first excavated the area. These inscriptions, created by Semitic-speaking laborers, are widely considered among the earliest examples of alphabetic writing, representing a transitional stage between Egyptian hieroglyphics and later Semitic alphabets.

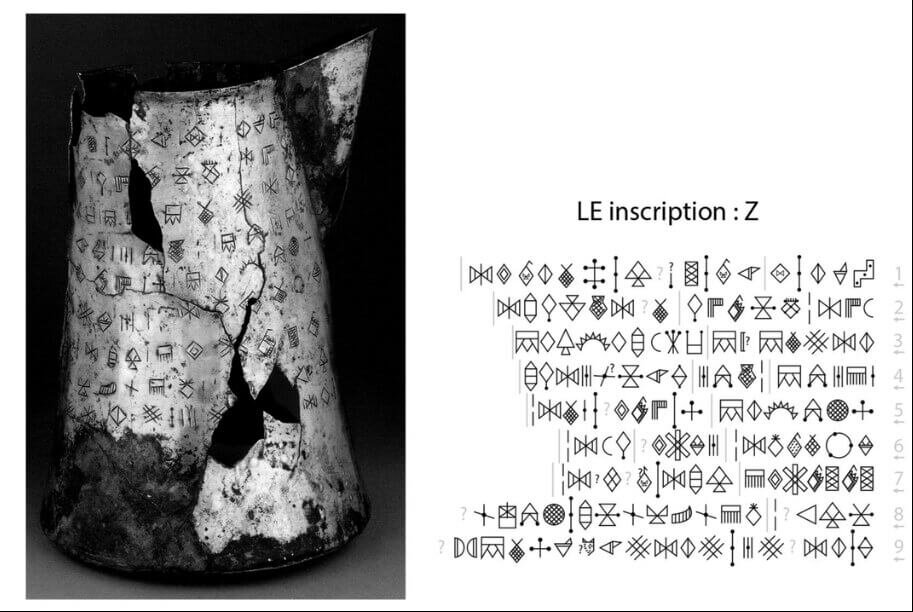

The ancient inscription that, according to Bar-Ron, reads, “This is from Moses.” (© 2025 Image Courtesy of Michael S. Bar-Ron All Rights Reserved, © 2025 Graphic Element by Patterns of Evidence Foundation)

Bar-Ron has focused on two inscriptions, cataloged as Sinai 357 and Sinai 361, which he interprets as containing the sequences "ZT MŚ" ("This is from MŚ") and "NʾUM MŚ" ("A saying of MŚ"). He argues that the combination "MŚ" could correspond to an early alphabetic rendering of the name Moses, making this a potentially groundbreaking epigraphic discovery. These inscriptions, according to Bar-Ron, function as signatures or authorial statements, which would imply a level of scribal literacy and self-representation among the Semitic workers who created them.

Additional elements found in other inscriptions at the site include references to the Semitic deity El, possible depictions of dissent or departure, and even imagery that has been associated with the "golden calf" episode from the Exodus narrative. These have been interpreted by Bar-Ron as indications of theological and ideological conflict between monotheistic Yahwistic groups and polytheistic cults devoted to deities such as Hathor or Ba‘alat.

Proto-Sinaitic Inscription, Sinai 349, with letters spelling, ‘Ba’alat,‘ the Semitic version of the Egyptian cow goddess, Hathor, highlighted. (© 2025 Image Courtesy of Michael S. Bar-Ron All Rights Reserved, © 2025 Graphic Element by Patterns of Evidence Foundation)

Support for Bar-Ron's hypothesis has come from some within the academic and biblical archaeology communities. His advisor, Dr. Pieter van der Veen, has publicly affirmed the plausibility of the interpretation. Various popular outlets and religious media have amplified the findings, suggesting that they may constitute early physical evidence confirming key figures and themes from biblical tradition.

However, the claims remain highly controversial and have not yet undergone formal peer review. Several scholars in the fields of Egyptology and Semitic epigraphy have expressed skepticism. Critics have noted that Proto-Sinaitic script remains only partially deciphered, and that assigning precise linguistic values to these inscriptions is fraught with uncertainty. The script’s characters are often ambiguous and open to multiple interpretations, particularly when found in isolated or eroded contexts.

Moreover, the use of the sequence "MŚ" as a reference to Moses is far from certain. While "Mose" or "Moshe" is a well-known Hebrew name, it is not unique in the ancient Near East, and similar consonantal structures appear in other names and words. The presence of such a sequence alone does not necessarily confirm a reference to the biblical figure, nor does it establish a historical connection to the Exodus tradition.

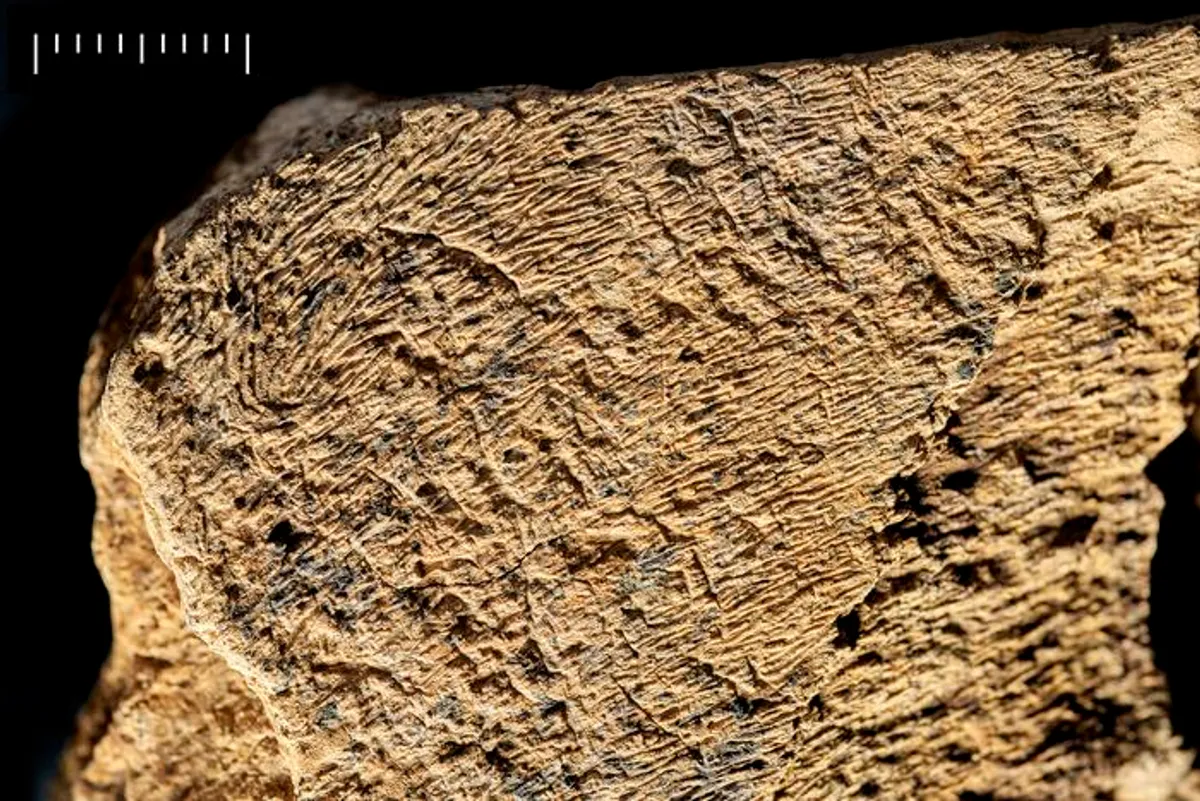

Bar-Ron’s scan of a Serabit el-Khadim inscription, with notes identifying pieces of this ancient writing. (© 2025 Image Courtesy of Michael S. Bar-Ron All Rights Reserved, © 2025 Graphic Element by Patterns of Evidence Foundation)

Scholars have also raised concerns regarding methodological rigor. Without broader archaeological context—such as stratified material layers, associated artifacts, or corroborative texts—the interpretation of brief and fragmentary inscriptions is speculative. The possibility remains that the glyphs reflect common graffiti, religious expressions, or names of ordinary laborers rather than statements by or about a singular historical figure.

In addition, the proposed connections between the inscriptions and the Exodus narrative are considered circumstantial. The absence of explicit references to Israel, the plagues, the crossing of the Red Sea, or Mount Sinai itself limits the extent to which the inscriptions can be seen as confirming biblical accounts. While some themes may overlap, they do not provide conclusive narrative parallels.

Despite these criticisms, the inscriptions are undeniably significant for the study of early alphabetic writing and the cultural exchanges that occurred in Egyptian-controlled regions of the Sinai during the Bronze Age. The Proto-Sinaitic script, generally believed to be the ancestor of Phoenician and ultimately all modern alphabetic scripts, demonstrates how Semitic-speaking laborers adapted Egyptian symbols to express their own language. This process marks a turning point in the history of writing, and the Serabit el-Khadim corpus remains central to understanding this development.

A scan of Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions, perhaps worshiping the Israelite deity El, that were found at Serabit el-Khadim, along with the possible signature of Moses. (© 2025 Image Courtesy of Michael S. Bar-Ron All Rights Reserved, © 2025 Graphic Element by Patterns of Evidence Foundation)

If further research, including high-resolution imaging, 3D scanning, and comparative epigraphic analysis, supports any of the proposed interpretations, it may encourage a reevaluation of the historical plausibility of some biblical narratives. Until then, the hypothesis that these inscriptions contain the name or signature of Moses remains a subject of debate.

Ongoing discussions are expected within academic circles, and further publications are anticipated. The case exemplifies the complexities of interpreting early inscriptions and the need for careful, multi-disciplinary scrutiny when drawing conclusions that intersect with deeply rooted historical and religious traditions.

In conclusion, while the findings at Serabit el-Khadim are certainly intriguing, they remain inconclusive. The identification of Moses in Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions is a hypothesis that must be tested against established epigraphic methods and broader archaeological evidence. As with many discoveries in ancient history, the balance between possibility and proof continues to shape the discourse.