Despite laying the foundations for many modern alphabets, the Phoenician civilization—famed for its seafaring prowess and cultural influence—appears to have left behind little to no genetic footprint. A new genetic study has puzzled scientists by revealing a striking disconnect between the widespread cultural legacy of the Phoenicians and their biological presence in the populations they once touched.

The Civilization That Changed the Mediterranean

The Phoenicians emerged around 3,000 years ago in the region of modern-day Lebanon. Descendants of the biblical Canaanites, they rapidly developed into a dominant maritime and commercial power. Trading in gold, silver, copper, and tin, they navigated vast Mediterranean trade routes and established hundreds of coastal colonies across Europe and Africa.

Until recently, scholars assumed that these settlers—known as the Punic peoples in later eras, such as the Carthaginians—would carry a clear genetic signature from their Levantine origins. It seemed logical that their descendants would bear DNA linking them back to the Eastern Mediterranean.

A Genetic Twist: Sicilian and Aegean Origins

But new genetic research has upended that belief. Population geneticist Harald Ringbauer and his team analyzed ancient DNA from the remains of 210 individuals unearthed at archaeological sites across the Middle East, North Africa, and Europe. The findings, recently published in Nature, were surprising.

"Most Punic individuals showed no Middle Eastern ancestry," the researchers wrote. "Instead, their genetic profile aligned more closely with that of ancient Sicilians and Aegean populations."

The genomes also revealed significant heterogeneity, suggesting that Punic populations were more of a cultural construct than a direct biological continuation of the original Phoenicians.

From Name to Identity

Interestingly, even the term “Phoenician” wasn’t their own—it comes from the Greek word phoinix, likely referring to the luxurious purple dye (Tyrian purple) they produced and traded extensively. The Phoenicians themselves referred to their identity as Kena’ani, or Canaanites, preserving a connection to their ancestral roots.

Carthage’s Expanding Role

The study also highlights the increasing genetic influence of North Africa on Punic populations, particularly through the rise of Carthage. Founded by Phoenician settlers, Carthage grew into one of the ancient world’s most powerful political and commercial hubs. Yet the DNA of its inhabitants doesn’t show a strong link to their Levantine founders.

Instead, it reveals extensive intermixing—evidence of centuries of cultural exchange and integration across the Mediterranean.

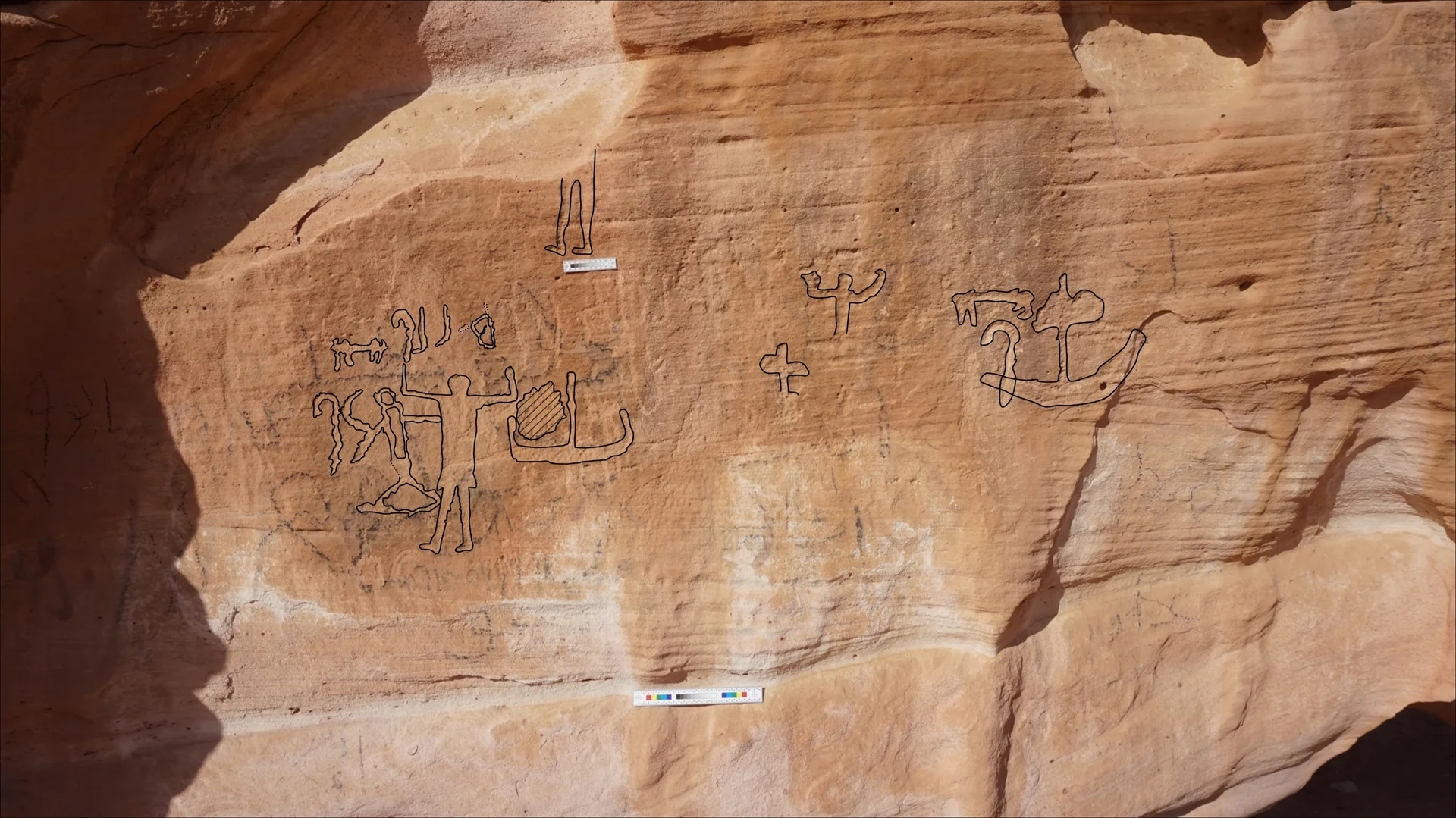

In Spain, a tomb at Villaricos revealed a family with genetic ties to Sicily and the Aegean, alongside grave goods like ostrich egg decorations and an ivory plaque—artifacts that reflect a vibrant and diverse cultural milieu.

While researchers noted Greek-style craftsmanship on the ivory plaque, such as the use of Ionian techniques, they caution that this doesn’t necessarily imply Hellenization. The Phoenicians were highly skilled artisans themselves, especially in ivory carving.

Cultural Survival Without Genetic Legacy

The team suggests that Phoenician cultural influence spread not through inheritance but through assimilation. Their language, technologies, and commercial practices were adopted by local populations—even as the Phoenicians’ genetic presence faded over time.

Adding to the mystery, the researchers note that prior to 600 BCE, the Phoenicians practiced cremation—a funerary custom that makes DNA recovery from earlier periods particularly challenging.

A Lasting Legacy Through Language

Although the name “Phoenician” stems from the Greek phoinix, possibly tied to their famous purple dye, the people themselves called their civilization Kena’ani. Their alphabet not only influenced the Greek writing system but also formed the basis of Latin, passing through the Etruscans before reaching the Romans.

Their DNA may have faded, but their influence—etched into scripts, trade routes, and craftsmanship—endures to this day.