For centuries, the story of Carthage has been told through the eyes of its destroyers. From Cato the Elder's relentless cry "Carthago delenda est" to Roman historians’ depictions of a savage and duplicitous foe, the memory of Carthage has suffered under the weight of imperial propaganda. But in recent years, the work of historian and archaeologist Dr. Eve MacDonald has emerged as a powerful corrective. Through meticulous scholarship and an eye for nuance, MacDonald has re-centered the Carthaginian narrative on the people who lived it — illuminating a cosmopolitan, technologically advanced, and politically complex civilization that once rivaled Rome. Her landmark books, Hannibal: A Hellenistic Life (2015) and Carthage: A New History (2026), are reshaping how we understand one of antiquity’s most vilified societies.

Rethinking Hannibal: The Hellenistic General

In her groundbreaking biography Hannibal: A Hellenistic Life, MacDonald moves beyond the tired dichotomy of Hannibal as a mere military genius or Rome’s mortal enemy. Instead, she paints a portrait of Hannibal as a quintessential Hellenistic figure: multilingual, philosophically literate, and steeped in the shared culture of the Eastern Mediterranean. Drawing on Greek, Roman, and Punic sources, MacDonald argues that Hannibal operated not as an outsider to Mediterranean politics, but as a participant in the same cultural and political dynamics that shaped figures like Philip V of Macedon or Antiochus III.

This re-framing aligns Hannibal with the broader world of Hellenistic diplomacy, charisma, and monarchical spectacle, placing him within — not against — the cultural fabric of the age. In doing so, MacDonald dismantles the Roman tendency to isolate Carthage as alien and instead re-integrates it into the classical world to which it fully belonged.

Carthage: A New History — Reclaiming a Civilization

While her earlier work reframed a central Carthaginian individual, MacDonald's Carthage: A New History takes on the grander task of narrating the entire arc of Carthaginian civilization from its Phoenician roots to its destruction in 146 BCE — and beyond. Departing from Roman caricatures of a city ruled by avarice and cruelty, MacDonald relies on archaeological data, Punic inscriptions, and re-evaluated classical texts to reconstruct the lived reality of Carthage.

She showcases a vibrant, urbanized society with democratic institutions, advanced maritime trade networks, and refined religious practices — including the controversial tophets, which she treats with critical sensitivity, separating archaeology from polemical accusation. Carthage, in her account, was not a cruel empire built on blood sacrifice, but a Mediterranean power defined by commercial ingenuity, civic organization, and cultural fusion.

Furthermore, MacDonald highlights Carthage’s intellectual and agricultural contributions to Roman culture. The agricultural handbook of the Carthaginian writer Mago, for example, was so highly valued by the Romans that it was translated into Latin after the city’s fall — a testament to the practical wisdom of a people otherwise dismissed as enemies of civilization.

Challenging the Roman Canon

MacDonald’s work is part of a broader trend in classical scholarship that seeks to decolonize antiquity by questioning inherited narratives rooted in conquest and cultural erasure. In her portrayal, Carthage ceases to be a convenient foil for Roman virtue and becomes a civilization in its own right, with its own internal logic, aspirations, and complexities.

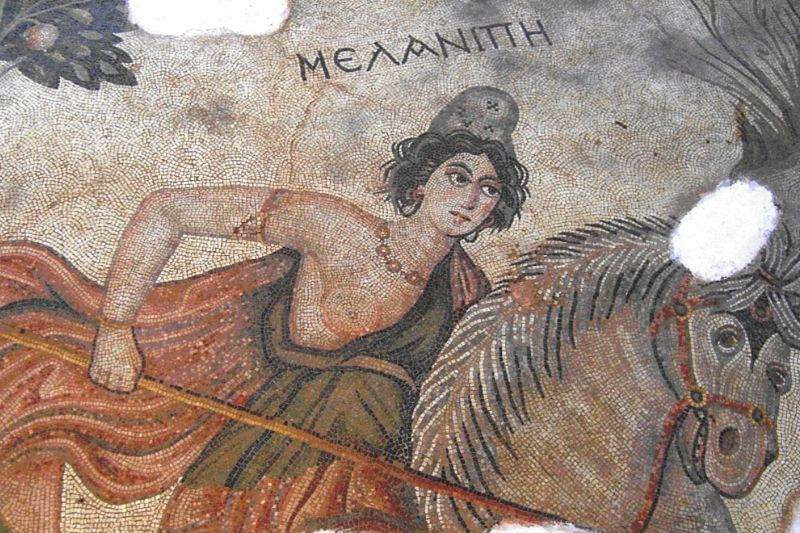

She also interrogates the myth of Carthaginian isolation, showing how Punic culture was deeply entangled with the Hellenistic world through trade, politics, and shared artistic motifs. Her analysis helps dismantle the "barbarian" trope so often assigned to Carthaginian society in both ancient texts and modern retellings.

Eve MacDonald’s scholarship invites us to look again — and more carefully — at a civilization long buried under Roman rhetoric and modern neglect. Through her works on Hannibal and Carthage, she not only reconstructs lost narratives but challenges the very frameworks through which we view the ancient world. In doing so, she returns dignity, depth, and humanity to a people too often remembered only as Rome’s defeated foe. Her history of Carthage is not just a new telling — it is an act of intellectual restoration.

As the field of ancient history continues to evolve, MacDonald’s work stands as a testament to the power of critical scholarship in rebalancing the scales of historical memory — ensuring that the voices of the past are heard not only through the words of their conquerors, but on their own terms.