A Bronze Relic Reemerges After Thirteen Centuries

More than 1,300 years after it was buried, a bronze plaque decorated with bears in a ritual pose has come to light once again in the forest-steppe of southern Siberia.

Discovered along the calm banks of the Chumysh River, the small but striking object is offering archaeologists fresh insight into cultural exchange and identity in a region shaped by shifting borders and empires. Though modest in size, the plaque tells a far-reaching story about belief systems and interaction at the fringes of the early Turkic world.

A Powerful Symbol at the Edge of Empires

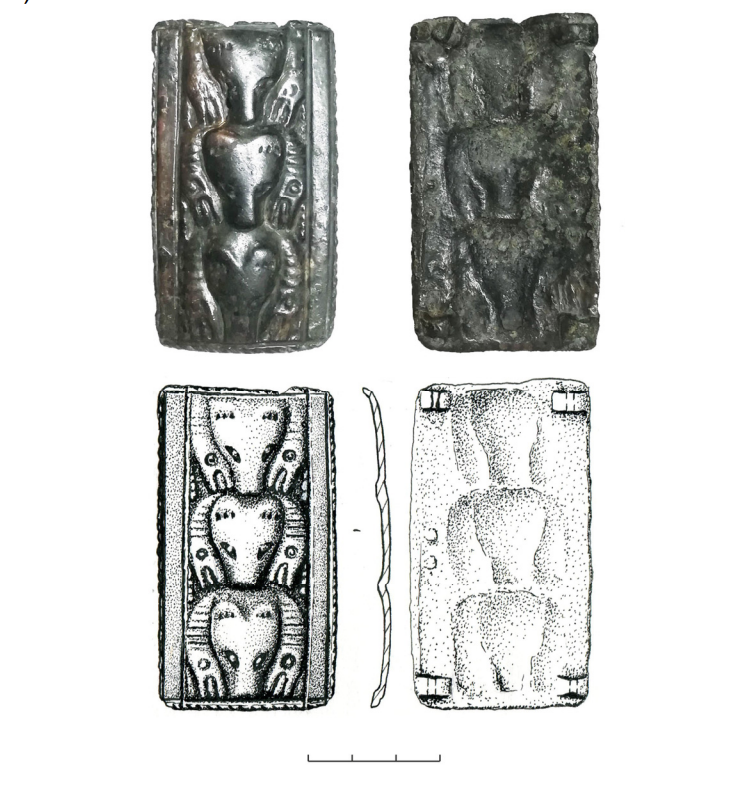

The artifact is a rectangular bronze plaque engraved with three bears arranged in a formal, sacrificial posture. Archaeologists recovered it from an early medieval burial site in Russia’s Altai region, dating it to the seventh or early eighth century AD.

What makes the find remarkable is its location. The plaque is now considered one of the southernmost examples of a symbolic tradition usually associated with the northern forests of Eurasia. Its appearance in the Altai forest-steppe is prompting scholars to rethink how far these cultural ideas spread—and how they were adapted in border regions during the early Middle Ages.

An Overlooked Cultural Crossroads

The burial ground, known as Chumysh-Perekat, sits in northeastern Altai Krai, where open forest-steppe landscapes gradually transition into the dense taiga of the Salair Ridge. For decades, this zone received little archaeological attention, eclipsed by the dramatic Altai Mountains to the south and the well-studied river systems of western Siberia to the north.

That changed when river erosion exposed human remains, leading to systematic excavations between 2014 and 2019. Teams from the Institute for the History of Material Culture of the Russian Academy of Sciences and Altai State University uncovered a rare, layered cemetery containing burials ranging from the Neolithic period to the early Middle Ages.

This made Chumysh-Perekat a unique archive of human activity spanning thousands of years.

Rare Burials, Rare Insights

Among the discoveries were seventeen early medieval graves that had largely avoided looting—an exceptional circumstance in this region. Intact burials from this period are uncommon in the forest-steppe Altai, giving researchers a rare opportunity to reconstruct everyday life, beliefs, and social structures along the northern edges of the Turkic Khaganates.

The Woman and the Bear Plaque

The bronze plaque was found in the grave of a woman believed to have been between 35 and 50 years old when she died. Although her burial showed signs of ancient disturbance, most of the grave goods were still present. Archaeologists suggest this disruption may have been ritual in nature rather than the result of theft.

The plaque shows three bear heads aligned vertically, each with forelegs folded beneath the body in what researchers call a “sacrificial pose.” Similar imagery is well documented in the taiga and forest regions of western Siberia, where bear symbolism played a central role in hunting rituals and spiritual traditions among Ugric and other northern groups.

Until now, however, such objects had almost never been found so far south.

Why the Discovery Matters

The presence of this plaque in southern Siberia is significant both geographically and culturally. It suggests that symbolic traditions linked to northern hunting cults reached much farther than previously thought—and that communities in this borderland zone were actively engaging with, adopting, or reinterpreting ideas from neighboring cultures.

In doing so, the bronze plaque adds a new layer to our understanding of cultural interaction during a pivotal period in Eurasian history, when identities were being shaped at the crossroads of forests, steppe, and empire.

Northern Symbols, Southern Style

What makes this burial particularly insightful is the combination of objects placed with the deceased. The woman was buried wearing jewelry and belt fittings commonly linked to southern nomadic traditions. These include pseudo-kolts—decorative pendants associated with early Turkic dress—as well as richly ornamented belt plaques.

Such items closely resemble finds from the Altai Mountains and Tuva, regions deeply connected to the emergence of early Turkic states. In contrast, the bear plaque clearly belongs to a northern symbolic tradition. Finding both together in a single grave points to more than simple exchange—it reveals a meaningful blending of cultural identities.

This was not a random or imported object placed in the burial by chance. Instead, it reflects a lived identity that drew simultaneously from northern belief systems and southern nomadic traditions.

Adoption, Not Imitation

The same pattern appears elsewhere in the cemetery. Several male burials included horses, a defining feature of Turkic funerary customs. However, instead of complete horse burials typical of the steppe, the animals were placed in segmented form—an intentional modification of the tradition.

Likewise, decorated belts—usually symbols of male warrior status in nomadic societies—were found not only with men, but also with women and children.

These choices suggest that local forest-steppe communities were not simply copying Turkic practices. They were actively adapting them, reshaping new cultural elements to fit their own social values and ritual traditions.

The result was a layered cultural environment where Samoyedic, Ugric, and Turkic influences coexisted and intertwined rather than replacing one another.

A Cultural Conversation at the Empire’s Edge

The bear plaque itself captures this cultural dialogue. Across northern Eurasia, bears carried deep spiritual meaning, often linked to ancestry, protection, and the structure of the cosmos. That symbolism endured even as Turkic political and cultural influence expanded northward during the seventh century.

Instead of wiping out older belief systems, nomadic expansion seems to have encouraged negotiation and adaptation. At the fringes of empire, identities were reshaped rather than erased.

Chumysh-Perekat provides a rare archaeological glimpse into that process—showing how communities at the crossroads of cultures forged new identities while holding on to older traditions.