The motif of two animals standing face-to-face in a symmetrical arrangement appears with remarkable frequency in ancient arts and ritual representations around the world. It constitutes a universal visual theme, where two animals are depicted confronting each other, usually symmetrically, often flanking a central figure or symbol. This motif is found from Mesopotamia and Egypt to Greece, Etruria, and Persia, and also in cultures of Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Oceania. This article examines:

The origin of the motif and its earliest appearances.

Examples from various civilizations, with emphasis on Mediterranean and Near Eastern cultures (Mesopotamia, Egypt, Minoan-Mycenaean Greece, Etruscans, Persians, Hittites, Phoenicians, etc.), but also references from Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Oceania.

Anthropological and psychological interpretations regarding the motif’s spread to geographically and culturally distant societies.

A brief overview of the motif’s development and continuity from antiquity to the 19th century.

Origin of the Motif

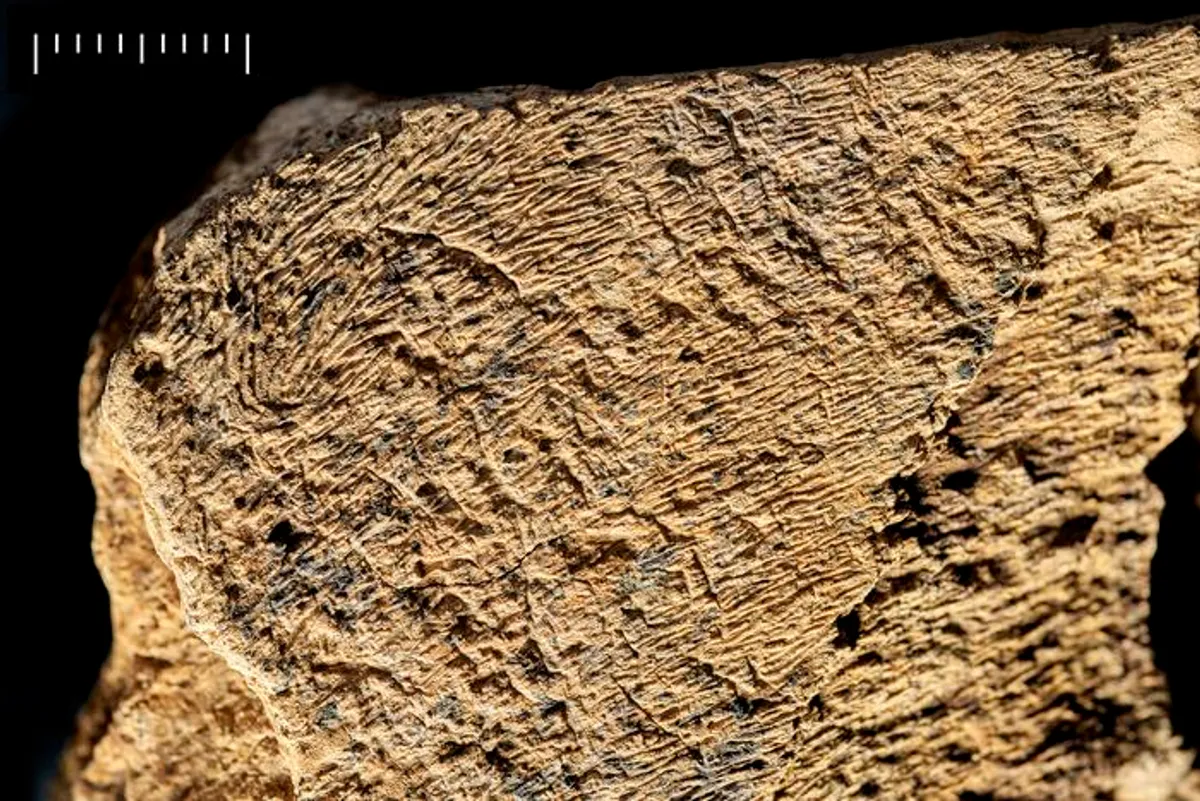

The origin of the confronted animals motif is rooted in the prehistoric era of the Near East. The earliest known examples appear around the end of the 4th millennium BC in Mesopotamia. In prehistoric seals and vessels from the region, already by the 5th–4th millennium BCE, we find pairs of animals in symmetrical arrangement. For example, cylinder seals from Uruk (~3000 BCE) depict two opposing lionesses (often described as mythical "serpopards" with features of serpent and leopard). Many seals also show two facing goats flanking a Tree of Life at the center, often placed upon a platform or hill—a composition already recognized from the 4th millennium BCE. These early depictions establish a motif of symmetry: two animals in perfect balance around a central axis, offering aesthetic harmony and likely symbolic meaning.

At the same time, other Late Neolithic cultures show similar imagery. A frequently cited example is the seated deity of Çatalhöyük (Neolithic Anatolia, ~6000 BCE), flanked by two felines in symmetrical pose. Some scholars consider this figure a primordial example of the Mistress of Animals archetype in the prehistoric world. Though the deity likely symbolized fertility and protection, the layout with two confronted animals already provides one of the earliest samples of the motif.

In Egypt and Mesopotamia of the 4th millennium BCE, we find parallel developments. A famous Egyptian artifact, the Narmer Palette (~3100 BCE), features on one side two large felines facing each other, their elongated necks intertwined in a symmetrical spiral design. These lionesses (originally interpreted as mythical "serpopards") are thought to symbolize the two kingdoms of Predynastic Upper and Lower Egypt, united under a single ruler. Their union, visualized through the interlinked animals, may reflect the consolidation under Pharaoh Narmer, with the lionesses representing the guardian deities of each kingdom (the lioness-goddesses Bast and Sekhmet). Thus, already at the dawn of history, the motif of confronted animals is associated with strong symbolism of unity and dominion.

Another ancient Egyptian artifact, the Gebel el-Arak knife handle (ca. 3400 BCE), depicts on one side a man—possibly a god or hero—between two confronting lions, which he grasps with his hands. This scene is an early instance of the related motif known as the Master of Animals, where a central human figure dominates between two symmetrically opposed animals. Overall, in both Mesopotamia and Egypt of the 4th–3rd millennium BCE, the motif appears fully developed: animals in opposing symmetry, either confronting each other or under the control of a central figure. The motif’s origin, therefore, can be traced to these early agrarian civilizations of the Fertile Crescent, from which it would spread widely.

Examples from Ancient Civilizations

Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East

In the civilizations of ancient Mesopotamia, the motif of confronted animals appears from the earliest seal impressions and remains popular throughout the 3rd and 2nd millennia BCE. Sumerian and Akkadian cylinder seals often depict symmetrical scenes with animals—two lions or bulls facing each other, sometimes with a human or demigod hero standing between them, restraining the animals. A recurring theme is the "naked hero" battling two lions or bulls simultaneously, symbolizing strength and civilization’s triumph over wild nature.

In other depictions, a tree or sacred pole appears at the center, with two ibexes (or other animals) symmetrically flanking it, forming the image of the Tree of Life. This motif—of a tree flanked by confronted animals—is extremely common in the art of the ancient Near East and the Mediterranean. It is often interpreted as symbolizing fertility and the vital force of nature, with the animals either protecting or feeding from the tree.

In Hittite and broader Anatolian tradition, similar patterns emerge. Although monumental Hittite art of the 2nd millennium BC left fewer relief scenes of two confronted animals flanking a central deity, it is known that the Hittites adopted many motifs from Mesopotamia. The gates of Hittite cities, such as the capital Hattusa, were adorned with carved stone lions placed symmetrically at each side of the entrance as threshold guardians.

Additionally, Hittite seals and small reliefs from the 18th–17th centuries BC (during the Assyrian trade colony period in Anatolia) abound in scenes of heroes or deities battling symmetrically arranged animals. Later, in the imperial period of the Hittites, the motif of the god standing atop a deer (a hunting deity) emerged, symbolizing dominance over wild beasts, although it is not a direct instance of the confronted animals motif. Overall, the Near East developed a rich iconographic repertoire in which the symmetrical depiction of animals was often associated with sacred power and protection.

The Phoenicians and other Eastern Mediterranean cultures of the 1st millennium BC further disseminated these motifs. Phoenician ivory carvings and metal vessels frequently depict sacred trees flanked by symmetrical animals such as ibexes, sphinxes, or lions, reflecting influences from Mesopotamia and Assyria. The motif of the Tree of Life flanked by confronted animals appears, for example, in Phoenician jewelry and reliefs, possibly symbolizing divine blessing and guardianship—where the paired animals act as protectors of the central sacred symbol.

In Imperial Persia (Achaemenid period, 6th–4th century BCE), although official art preferred continuous friezes of processional animals, there are indications of continuity for the confronted animals motif. The famous friezes of Persepolis feature lions and bulls in dynamic interactions—not symmetrically confronted but often in combat. However, in Persian decorative art and textiles, the confronted animals motif flourished. A notable example is the Persian decorative medallion (roundel) in textiles and carpets, often depicting two animals facing each other within a circular frame—a motif rooted in the tradition of animal compositions from the Asian steppes.

This Persian tradition was transmitted via the Silk Road to China during the Tang dynasty, where Chinese weavers adopted the motif in their own designs. Thus, the pair of confronted animals, often framed within decorative borders, became an international motif in textile and minor arts of late antiquity.

Jade Openwork Disc with Dragon and Phoenix, China, 2nd century BC, Museum of the Mausoleum of the Nanyue King

Ancient Egypt

Beyond the Predynastic examples already discussed—such as the Narmer Palette and the Gebel el-Arak knife—the motif continued in various forms during the Pharaonic period. Ceremonial palettes from the late 4th millennium BC were often adorned with reliefs showing confronted animals. Besides lionesses, these included hippopotamuses, giraffes, geese, and other creatures. Even symmetrical representations of trees or palm fronds appeared, establishing a recurring motif of bilateral symmetry.

In Egyptian religious art, the motif became closely associated with protection and order. Confronted lionesses could symbolize guardian deities such as Bast and Sekhmet, flanking the pharaoh. In Egyptian mythology, the motif of two lions seated back-to-back (anti-confronted), known as Akeru, represented yesterday and tomorrow with the rising sun between them. Although reversed, this composition reflected the symbolic use of paired animals flanking a cosmic principle.

In the New Kingdom and later periods, the motif persisted through sphinxes and guardian lions placed in symmetrical pairs at temple entrances or palace avenues—such as the ram-headed sphinxes lining the processional avenue in Thebes. Relief scenes frequently depicted goddesses in animal form or with animal heads shown symmetrically. The goddess Hathor, for example, often appeared doubled as two cows flanking the sun or the pharaoh, underscoring cosmic balance and divine guardianship.

Minoan and Mycenaean Greece

In the prehistoric Aegean, the motif of confronted animals held a special place, often linked with nature deities. In Minoan Crete (2nd millennium BCE), the figure of the Mistress of Animals (Potnia Theron) appears in frescoes and seals, flanked symmetrically by animals. A well-known example is the Snake Goddess (~1600 BCE), depicted with uplifted arms holding serpents on each side—clearly a variation of the motif. These snakes, sacred symbols, flank the goddess symmetrically and emphasize her dominion over nature and apotropaic power.

Seals and frescoes from Minoan palaces show pairs of ibexes, bulls, or lions flanking central elements like trees or altars. Gold jewelry, such as the famous Bee Pendant from Malia, represents two bees or insects symmetrically facing a central orb—a microcosmic variation of the same visual logic.

THE “SNAKE GODDESSES” AND OTHER MINIATURE OBJECTS FROM THE TEMPLE REPOSITORIES

The most important cult objects from the Knossos Temple Repositories are the figurines of the “Snake Goddess.” They are named after the snakes twining around the body and arms of the larger figure and the two snakes that the smaller figure holds in her upraised hands.

The snakes symbolize the chthonic character of the cult of the goddess, while the feline creature on the head of the smaller figure suggests her dominion over nature. The exposed and voluptuous garments, consisting of a long flounced skirt, tight-fitting bodice, and a close-fitting bodice that exposes the figure's breasts, symbolize the fertility of women, the goddess, and, by implication, nature itself.

The large rock-crystal rosette and stone cross are astral symbols. Knossos–Temple Repositories, 1650–1550 B.C.

Photo by Dimosthenis Vasiloudis

In Mycenaean Greece (~1600–1100 BCE), the motif reached monumental scale in the Lion Gate at Mycenae (~1250 BCE). The relief above the gate features two lionesses standing symmetrically on a pedestal, their forepaws resting on a central column. The column is interpreted as a symbolic representation of a deity or sacred space, perhaps a stand-in for the Mycenaean Great Goddess. Some scholars believe it represents the palace gate or a sacred grove, with the lionesses acting as protectors of the royal and sacred precinct.

Mycenaean seals and rings also frequently depict heroes or deities grasping animals by the neck in symmetrical positions, echoing the Master of Animals motif.

Etruscans and the Western Mediterranean

In the 1st millennium BCE, the Etruscans of Italy adopted many Orientalizing motifs through trade with Greece and the Near East, including the confronted animals motif. A characteristic example is the Tomb of the Leopards in Tarquinia (~5th century BCE), where two leopards appear above a symposium scene, facing each other symmetrically. Though decorative, the animals also served as guardians of the banquet in the afterlife.

Similar motifs appear in Etruscan metalwork and ceramics, where pairs of feline or other animal forms flank sacred trees or objects. These were likely apotropaic or indicative of prestige. The Romans, continuing these traditions, embraced symbolic dualities such as the Dioscuri (twin heroes) depicted symmetrically or the Capitoline Wolf suckling the twins—another expression of dual guardianship.

In Carthage, a Phoenician colony in North Africa, the motif survived in adapted forms, particularly in the depiction of sacred trees flanked by confronted animals, echoing Phoenician and Mesopotamian prototypes.

Overall, across the ancient Mediterranean—from the Near East and Egypt to the Aegean and Italy—the image of two symmetrical animals facing each other recurs with striking consistency. Whether lionesses at city gates, sphinxes at tombs, goats flanking sacred trees, or winged creatures on jewelry, the motif was employed to convey power, sanctity, and protection.

Other World Civilizations

Sub-Saharan Africa

In sub-Saharan Africa, although confronted animal motifs are not as systematically represented as in the ancient Near East, we find important and meaningful instances. A particularly notable example comes from the Kingdom of Benin (present-day Nigeria). The Benin bronze plaques of the 16th–17th centuries CE, which once adorned the royal palace, include depictions of the Oba (king) holding two leopards—one in each hand—standing symmetrically on either side. The leopard, considered the "king of the forest," symbolized the Oba’s alter ego and conveyed royal power and dominion over nature. This scene is a clear African expression of the Master of Animals motif and reveals the symbolic use of confronted animals to represent sovereignty and supernatural control.

Asia (Beyond the Near East)

In the Indian subcontinent, seals from the Indus Valley Civilization (ca. 2500–1900 BCE) show horned deities flanked by various animals—elephants, tigers, rhinoceroses, and buffaloes—though not always in perfect symmetry. The most famous, the so-called “Pashupati” seal, shows a deity in yogic posture surrounded by animals, a precursor to the later Hindu concept of Shiva as Lord of Beasts.

In Chinese tradition, mythical creatures like the dragon and phoenix often appear in symmetrical pairs, especially in imperial contexts, symbolizing the emperor and empress, or cosmic duality. Jade amulets from the Han dynasty show these creatures in a face-to-face arrangement. In the Mawangdui tomb banner (2nd century BCE), a human deity with outstretched arms holds serpents or dragons at either side—another example of a central figure with flanking animals.

In Southeast Asia and Oceania, traditional art also expresses the principle of symmetry. In Papua New Guinea and Indonesian carving traditions, we find representations of birds, reptiles, or totemic creatures in balanced, symmetrical positions, often in ritual or architectural contexts. While not as systematic as in the Fertile Crescent, the appearance of symmetrical animal pairs reveals a universal aesthetic and symbolic impulse.

Pre-Columbian Americas

In the Americas, the motif appears with regional variations. In Mesoamerica, the Aztec calendar stone features two massive serpents facing each other at the base, symbolizing cosmic cycles. The twin heroes of Mayan mythology, though anthropomorphic, reflect duality and symmetry as sacred principles. Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent deity, is sometimes depicted between flanking animals, signifying his control over the natural world.

In the Andean region, Chavín art (1st millennium BCE) presents the Staff God holding two animal-headed staffs, surrounded by rows of symmetrical animal forms (eagles, serpents, felines). The Sun Gate at Tiwanaku shows a central deity—possibly Viracocha—holding staffs and flanked by confronting animal forms. These examples, found across the globe, demonstrate the motif’s transcultural resonance.

Lithograph of Powhatan's Mantle

E. T. Shelton (photograph, ca. 1888); P. W. M. Trap (lithography, ca. 1888)

Anthropological and Psychological Interpretations

The recurrence of the confronted animals motif in such diverse and geographically distant cultures invites a deeper anthropological and psychological analysis. Why has this motif appeared independently or been adopted so widely? What symbolic or functional needs does it fulfill?

1. Aesthetic Symmetry

One foundational explanation lies in the human attraction to symmetry. Bilateral symmetry is a fundamental feature of the natural world—from the human body to countless animals and plants. Thus, the human mind is predisposed to perceive symmetrical arrangements as orderly, harmonious, and pleasing. Two animals in mirrored confrontation form a closed, balanced composition. Psychologically, such balance symbolizes order over chaos—a central concern for early civilizations seeking to impose structure on a hostile or untamed environment. Independent of any specific religious or cultural meaning, the motif likely proliferated simply because it appealed to the human eye and psyche.

2. Symbolism of Power and Control

In many instances, particularly where a human or divine figure stands between the animals, the motif conveys power and dominion. Anthropologists have long observed that the Master of Animals scene often reflects elite or royal ideology. The hero or god subduing two beasts becomes a metaphor for the ruler who tames the wilderness, enforces order, or defends civilization. Examples range from Mesopotamian cylinder seals of the king battling lions to the Benin Oba gripping leopards. Even when the human figure is absent, the animals flanking a sacred symbol may imply guardian functions. Lions at Mycenaean gates or leopards in Etruscan tombs operate as sentinels at thresholds—between life and death, profane and sacred.

3. Duality and Cosmic Balance

Many cultures organize their cosmologies around dualities: light and dark, male and female, life and death, and earth and sky. Confronted animals often express these paired principles in visual form. In the Narmer Palette, the lionesses may represent Upper and Lower Egypt unified. In China, the dragon and phoenix reflect yin and yang. A tree flanked by goats might signify the union of terrestrial vitality with celestial ascent. Scholar Elvyra Usačiovaitė points out that a typical ancient archetype features two mirrored figures with a tree between them—sometimes kings or gods, or even deity and devotee—suggesting cosmic cooperation or harmonious balance.

Psychologically, the confrontation of equal animals suggests rivalry brought into balance. Neither overpowers the other; the symmetry embodies equilibrium, perhaps symbolizing the stable world order desired by ancient peoples. The motif may reflect a deep psychological need in humans to endure the weight of a world that surrounds and defines them before they even understand or choose it. People are born into a world already full of laws, symbols, natural forces, and social expectations—all of which exert pressure and seem overwhelming.

The symmetrical depiction of animals, especially when flanking a central figure, creates a sense of balanced order where one can safely stand and recognize themselves as an active being. Whether the central figure is a hero, a deity, or a symbolic human, its position between two facing beasts conveys the hope that chaos can be ordered and that the powers of nature can be controlled or coexist in harmony. The motif thus becomes a vessel for a timeless human desire: to believe that we are not at the mercy of the world, but that there is a center of meaning or strength that transcends and supports us.

4. Religious and Ritual Function

The motif is frequently found in religious or ceremonial contexts—on altars, temple gates, tombs, and sacred items—suggesting it served a spiritual purpose. Animals might embody guardian spirits, divine protectors, or totemic ancestors. Their symmetrical stance flanking a sacred object or space may act as an invocation, ward, or symbol of divine presence. The motif may have been used in initiation rites or cosmological teachings, conveying notions of balance, order, or divine oversight.

Though specific meanings varied across cultures, the form was adaptable—used to express fertility (animals flanking a Tree of Life), authority (a god or king between lions), or transcendence (sphinxes guarding sacred precincts).

5. Diffusion and Independent Invention

The global presence of the motif results from both cultural diffusion and independent development. Archaeological evidence supports diffusion: motifs traveling along trade routes from Mesopotamia to Anatolia, the Aegean, and eventually to Persia and China via textiles. Yet even in cultures without contact, the motif emerged independently—evidence of a shared human symbolic imagination. Across cultures, people sought to depict their mastery of nature, express duality, and sanctify space. The confronted animals motif met all these needs, both practically and spiritually.

In conclusion, no single interpretation exhausts the motif's meaning. It was polyvalent—sometimes ornamental, sometimes sacred, and sometimes royal. Its universality reflects shared human values: awe of the animal world, love of symmetry, and the need for symbols bridging the natural and the divine.

Later Continuity and Evolution of the Motif

The motif of confronted animals did not disappear with antiquity; instead, it was preserved and transformed across later periods, enduring into the 19th century. As religions, artistic traditions, and symbolic systems evolved, the motif adapted to new contexts while retaining its core principle—two entities in symmetrical confrontation.

Classical Antiquity and Early Christian Art

During the Greco-Roman period, the motif persisted, although less dominantly. In Greek art, the goddess Artemis as Potnia Theron was often shown with animals on either side—sometimes holding a stag in each hand—reiterating the visual theme of control over nature. Such imagery continued into Roman decorative contexts, where the idea of symmetrical flanking persisted in designs associated with deities, heroes, or cosmic concepts.

Medieval Europe

The motif found renewed vitality in medieval Europe, especially through contact with animal-style art from the steppe cultures. Germanic, Anglo-Saxon, and Viking art embraced symmetrical animal compositions, often highly stylized. One of the most famous examples is the Sutton Hoo purse lid (~7th century CE), which features three sets of confronted animals. On the outer panels, anthropomorphic figures grip wolves in symmetrical opposition; the central design includes a more abstract pair of confronted beasts in intricate interlace.

Purse-lid from the Sutton Hoo ship-burial 1, England. British Museum.

Rob Roy User:Robroyaus on en:wikipedia.org

Celtic and Insular art followed similar aesthetics. In illuminated manuscripts like the Book of Kells, human and animal figures appear in mirrored, often interwoven poses. The Viking art style known as "gripping beasts" continued this trend into the 11th century, showing confronted animals whose limbs or tails interlock in elaborate patterns.

Romanesque and Gothic Architecture

In Romanesque art (11th–12th centuries CE), the motif reappears in architectural sculpture. Church capitals and tympanums often show two dragons, lions, or other creatures facing each other, forming arches over windows and portals. These often had moral or apotropaic meanings, symbolizing the conflict between good and evil or acting as spiritual protectors.

Heraldry and Early Modern Symbolism

In medieval and early modern heraldry, the motif became codified in the form of "supporters"—animals flanking a coat of arms. Since the late Middle Ages, these have included lions, unicorns, eagles, and other creatures standing symmetrically on either side of a heraldic shield. The British royal arms, for instance, feature a lion and a unicorn as confronted supporters. Here, the ancient visual logic is maintained, with the animals no longer guarding a tree or deity but instead a symbol of state authority.

Romanesque capital, northern outside of the main apse of Basel Minster

HajjiBaba - Own work

Islamic and Renaissance Decorative Arts

In Islamic art, especially in textiles and carpets from the 13th to 15th centuries CE, the motif of two confronted animals surrounding a tree or medallion flourished. These “animal carpets” from Anatolia often showed mythical or real animals (dragons, phoenixes, deer, birds) in face-to-face symmetry within circular frames. The motif symbolized harmony, divine order, or heavenly gardens. These carpets were exported to Europe and depicted in Renaissance paintings as luxury objects.

In Renaissance Europe, the motif was often used decoratively. It appeared on tapestries, manuscript borders, and architectural friezes. The aesthetic value of symmetrical animal pairs outweighed their mythological significance, yet their symbolic resonance with antiquity remained strong.

Into the 18th and 19th Centuries

The motif continued into neoclassical and Romantic-era Europe, appearing in sculpture, architecture, and decorative design. Guardian lions flanking the entrances of neoclassical buildings, animal motifs on heraldic devices, and even national symbols like the double-headed eagle (a variation of the motif) sustained the ancient tradition.

Folk art, too, retained versions of the motif. European textiles, embroidery, and ceramics of the 18th–19th centuries often featured confronted horses, birds, or floral elements, reaffirming the enduring appeal of bilateral animal symmetry. Even when its origins were forgotten, the form continued to serve its functions: aesthetic harmony, symbolic balance, and cultural identity.

Animal carpet, Turkey, dated to the 11th–13th century, Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

The motif of confronted animals is one of the most enduring and universal in human artistic expression. From early Mesopotamian seals and Egyptian palettes to medieval manuscripts and 19th-century folk textiles, the image of two animals facing each other across a central axis has communicated a wealth of meanings.

Its persistence across millennia and continents suggests that it satisfies deep cognitive and symbolic needs. Whether representing divine guardianship, cosmic order, royal power, or pure visual balance, the motif was infinitely adaptable. Each culture integrated it into its own visual and symbolic vocabulary, and each time it was slightly reinvented—yet always recognizable.

At its heart, the motif reminds us that the human imagination is both universal and diverse. Across time and space, people have seen in the mirrored gaze of two animals not just an image, but a symbol of unity, guardianship, power, and equilibrium. It is a visual language that continues to echo in our collective memory.