A groundbreaking study combining archaeology and ancient DNA is rewriting what we know about how farming and sedentary life spread through prehistoric Anatolia.

The rise of agriculture—arguably one of the most transformative shifts in human history—didn’t always move with migrating people. Instead, new research shows that in parts of ancient Anatolia, it was ideas, not farmers, that traveled the furthest.

This revelation comes from a Turkish-Swiss collaboration, published in Science, where researchers used a rare combination of ancient genome sequencing and large-scale archaeological data to untangle a long-standing debate: Did farming spread by cultural diffusion or population movement? The answer is more nuanced than previously imagined.

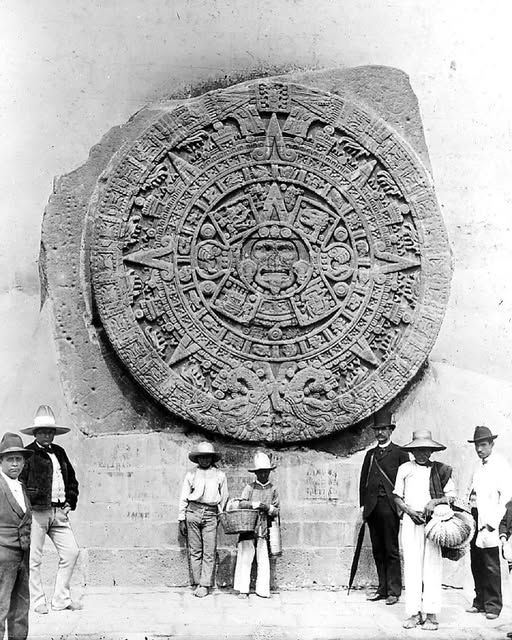

The Birthplace of Farming and a Puzzle of Movement

Modern-day Turkey, home to the Fertile Crescent’s western edges, was central to the Neolithic revolution. Around 10,000 years ago, communities here began the radical shift from hunting and gathering to settled village life with domesticated plants and animals.

Until now, scientists assumed that this change spread into neighboring regions primarily through migration. But the new study—led by experts from Middle East Technical University, Hacettepe University, and the University of Lausanne—suggests a more complex story.

“In some regions of West Anatolia, we see major cultural transitions, but without evidence of new populations arriving,” says Dr. Dilek Koptekin, lead author. “People didn’t move—but their ideas did.”

Genetics Meets Pottery: A Revolutionary Method

To reach these conclusions, the team sequenced the oldest known genome from West Anatolia, a 9,000-year-old individual, along with 29 other newly recovered ancient genomes. Surprisingly, across 7,000 years of settlement, the genetic signatures remained strikingly consistent—even as the material culture changed drastically.

“People moved out of caves, built homes, adopted new tools and rituals—all without being replaced by incoming populations,” explains Dr. Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas, a computational biologist at UNIL. “This clearly points to cultural transmission over mass migration.”

But the study didn’t stop with genetics.

The researchers also developed a novel approach to quantify archaeological data—assigning numerical values to artifacts like pottery styles, tools, and architectural features from hundreds of published sources. This allowed them to systematically match cultural shifts with genetic data from the same regions and timeframes.

“We finally had a way to directly compare how cultural practices spread in relation to biological ancestry,” says archaeologist Çiğdem Atakuman from METU. “This was a first.”

Not All Pots Mean People

The findings challenge the long-standing archaeological saying: “Pots don’t equal people.”

In West Anatolia, at least, the saying holds true. Communities took on new lifestyles without being genetically replaced. Farming and village life emerged not from colonization, but from cultural influence—perhaps via trade, seasonal visits, or symbolic exchanges.

However, other regions told a different story.

Around 7,000 BCE, DNA reveals clear signs of population movement and admixture in central and Aegean Anatolia. Here, both genes and ideas traveled together, signaling a new wave of migrations that would later push into Europe.

“The Neolithic was not one-size-fits-all,” says Dr. Füsun Özer of Hacettepe University. “It was a mosaic of local adaptations, cultural exchanges, and, in some places, true migration.”

Why It Matters: A New Model of Human Change

The study’s broader impact lies not just in what it reveals about the Neolithic, but how it was done. By integrating archaeological and genetic data at this scale, the researchers offer a new model for understanding ancient human transitions—one that moves beyond simplistic narratives of replacement or isolation.

“Humans don’t need a crisis or invasion to change,” says Koptekin. “We’re naturally innovative, curious, and open to new ways of life.”

A Call for Global, Inclusive Research

The study also highlights the value of locally led research. Unlike many high-profile genetics papers that center on labs in North America or Western Europe, this project was conceived and led by researchers in Turkey—the very region under study.

“It shows how powerful science can be when research is rooted in the communities and landscapes it investigates,” says Malaspinas. “This should be the model moving forward—more inclusive, more global, and more collaborative.”

Bottom Line:

The shift to farming in Anatolia wasn’t a single process—it was a patchwork of movement, tradition, and innovation. In many places, ideas outpaced people, changing the world without changing who lived in it.

This study not only reshapes our understanding of the Neolithic—it also opens the door to new, more sophisticated ways of exploring how humans adapt, exchange, and evolve.