For the first time ever, hominin fossils have been found beneath the sea floor of Sundaland—offering rare, tangible evidence that our early human ancestors once roamed these now-submerged lowlands.

A recent study led by Dr. Harold Berghuis and published in Quaternary Environments and Humans reveals that one of these fossils—recovered during a routine construction dredging operation—belongs to Homo erectus, a key player in the human evolutionary story. These are the first hominin fossils ever recovered from the submerged regions of Sundaland, a vast expanse of land that connected parts of Southeast Asia during the Pleistocene era.

The Forgotten Land Beneath the Waves

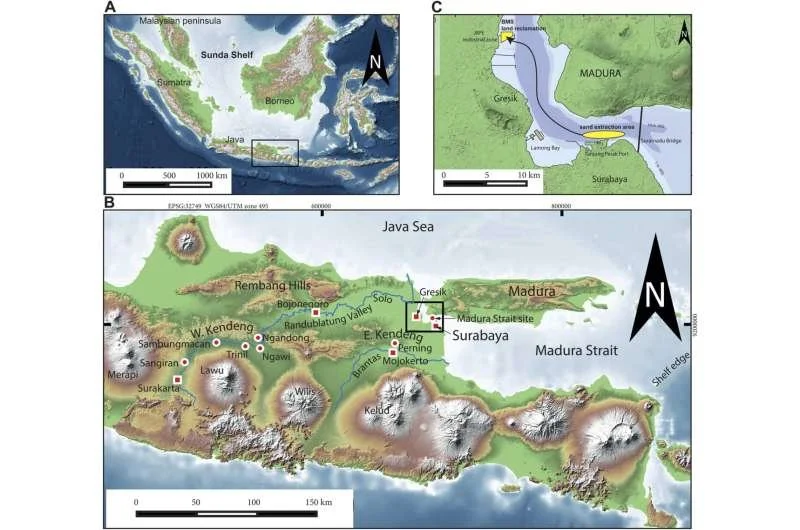

Much of what we know about ancient hominins in Southeast Asia comes from fossils found on present-day land: Java, Flores, Luzon. But during the Ice Age, sea levels dropped dramatically, exposing a massive landmass—Sundaland—that linked modern-day Indonesia, Malaysia, and parts of mainland Asia. This now-submerged region was once a continuous stretch of plains, valleys, and river systems, potentially teeming with hominins like Homo erectus.

Despite this potential, the seabed has remained largely unexplored. The main obstacle? Access. Excavating underwater sediments is expensive and usually only happens during industrial projects—like the one that led to this discovery.

How Construction Uncovered a Deep Past

In 2014–2015, the port company Berlian Manyar Sejahtera (BMS) initiated a large-scale land reclamation project near Surabaya, Indonesia. Over 5 million cubic meters of seabed sand were dredged to create a 100-hectare artificial island for cargo operations.

Later inspection of the newly formed island revealed an unexpected treasure: thousands of fossilized vertebrate remains—6,732 specimens in total—including two hominin fossils, now dubbed Madura Strait 1 (MS1) and Madura Strait 2 (MS2).

What the Fossils Tell Us

After rigorous comparative analysis, Dr. Berghuis and his team identified MS1 as belonging to Homo erectus, specifically resembling late Middle Pleistocene Javanese individuals dating to 140,000–92,000 years ago. MS2 was harder to pin down but appears to belong to an archaic Homo species.

This discovery extends the known range of Homo erectus beyond Java, suggesting they spread across Sundaland’s now-submerged lowlands during the Middle Pleistocene.

“It’s the first solid fossil evidence from underwater Sundaland,” said Dr. Berghuis. “It proves that hominins—specifically Homo erectus—occupied these lowland plains before they were swallowed by the sea.”

Ancient Landscapes, Modern Mysteries

Geological analysis places the fossil site within Marine Isotope Stage 6 (MIS6)—a glacial period around 160,000 to 120,000 years ago when sea levels were lower, and Sundaland was exposed.

The researchers ruled out the possibility that the fossils were reworked from older deposits. The sediment layers, depth of the site, and uniform mineralization of the fossils all point to in-situ deposition rather than later disturbance.

The broader fossil assemblage paints a picture of a dry, open landscape, populated by now-extinct species like Stegodon trigonocephalus and Duboisia santeng—herbivores that would have shared their habitat with hominins.

The High Cost of Discovery

Why haven’t more fossils been found in Sundaland’s submerged terrain?

“Extracting seabed sand is very expensive,” Dr. Berghuis notes. “We typically only get access to these materials during large-scale construction. That’s why it’s critical for scientists to collaborate with port authorities and developers.”

He adds, “We may one day see another dredging operation nearby. If that happens, having paleontologists involved from the start could be crucial.”

Why It Matters

This find fills a significant gap in our understanding of early human migration in Southeast Asia. It supports the idea that hominin populations moved across Sundaland—not just between isolated islands—and highlights how much of human history is still hidden beneath the waves.

It also raises new questions:

How far did these early humans spread?

What other species may lie buried beneath the seabed?

And how much more are we missing simply because of lack of access?

One thing is clear: Sundaland holds secrets, and we’ve only just begun to unlock them.