Most people can trace their family tree back at least a few generations, while the more serious ones are able to accomplish many centuries. But imagine being able to trace your lineage back to a 5,300-year-old mummy. That is exactly what has happened after scientists performed DNA tests on ‘Ötzi the Iceman’ and found 19 living male descendants in Austria.

Ötzi the iceman, who was discovered by some German tourists in the Alps in 1991, was originally believed to be the frozen corpse of a mountaineer or soldier who died during World War I. Tests later confirmed the iceman dates back to 3,300 BC and most likely died from a blow to the back of the head. He is Europe’s oldest natural human mummy and, remarkably, his body contained the still intact blood cells, which resembled a modern sample of blood. They are the oldest blood cells ever identified. His body was so well-preserved that scientists were even able to determine that his last meal was red deer and herb bread, eaten with wheat bran, roots and fruit.

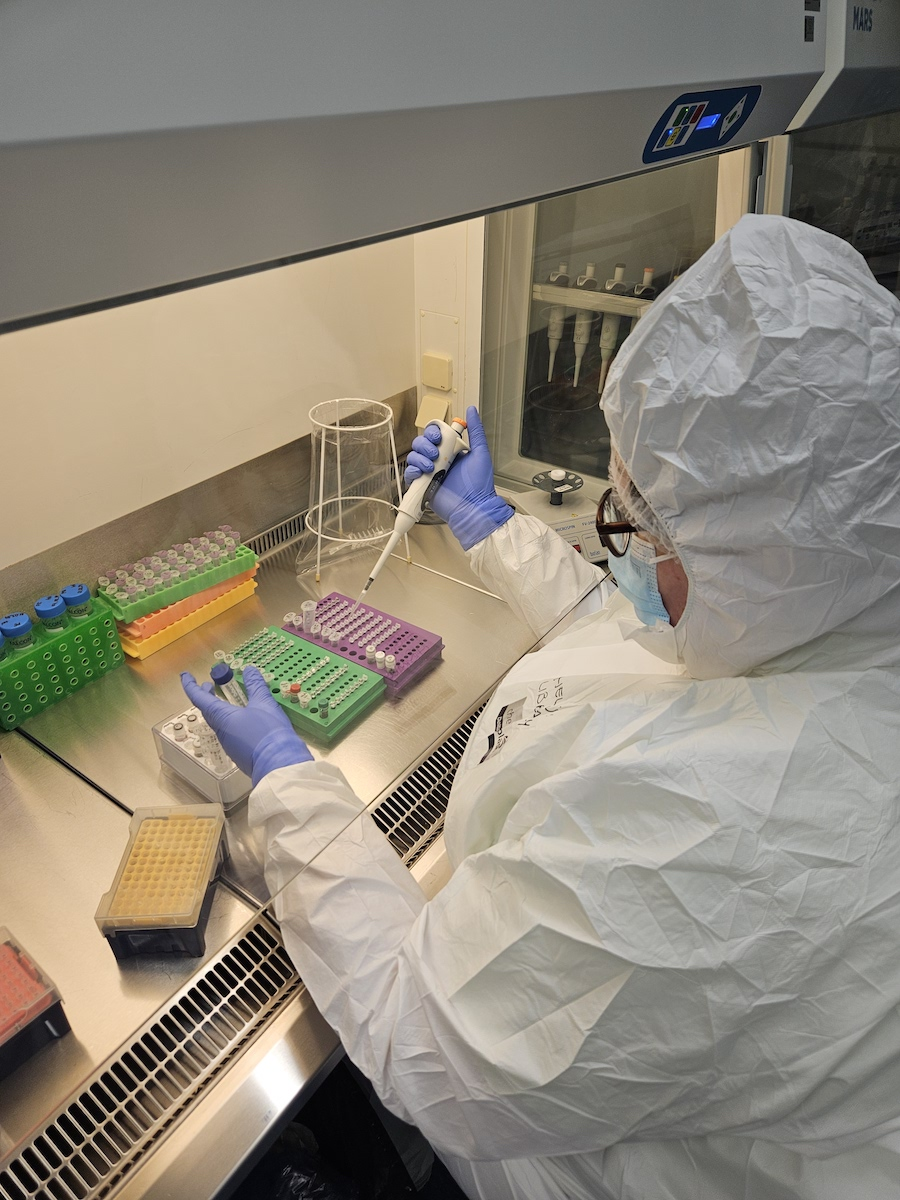

A DNA analysis showed him at high risk of atherosclerosis, lactose intolerance, and the presence of the DNA sequence of Borrelia burgdorferi, making him the earliest known human with Lyme disease. Researchers were able to identify Ötzi’s relatives by finding individuals who shared his same genetic mutation.

“There are parts of the human DNA, which are generally inherited unchanged. In men this lies on the Y chromosomes and in females on the mitochondria. Eventual changes arise due to mutations, which are then inherited further,” said Walther Parson, the forensic scientist who carried out the study. “This is the reason why we can categorize people with the same people into so-called haplogroups.”

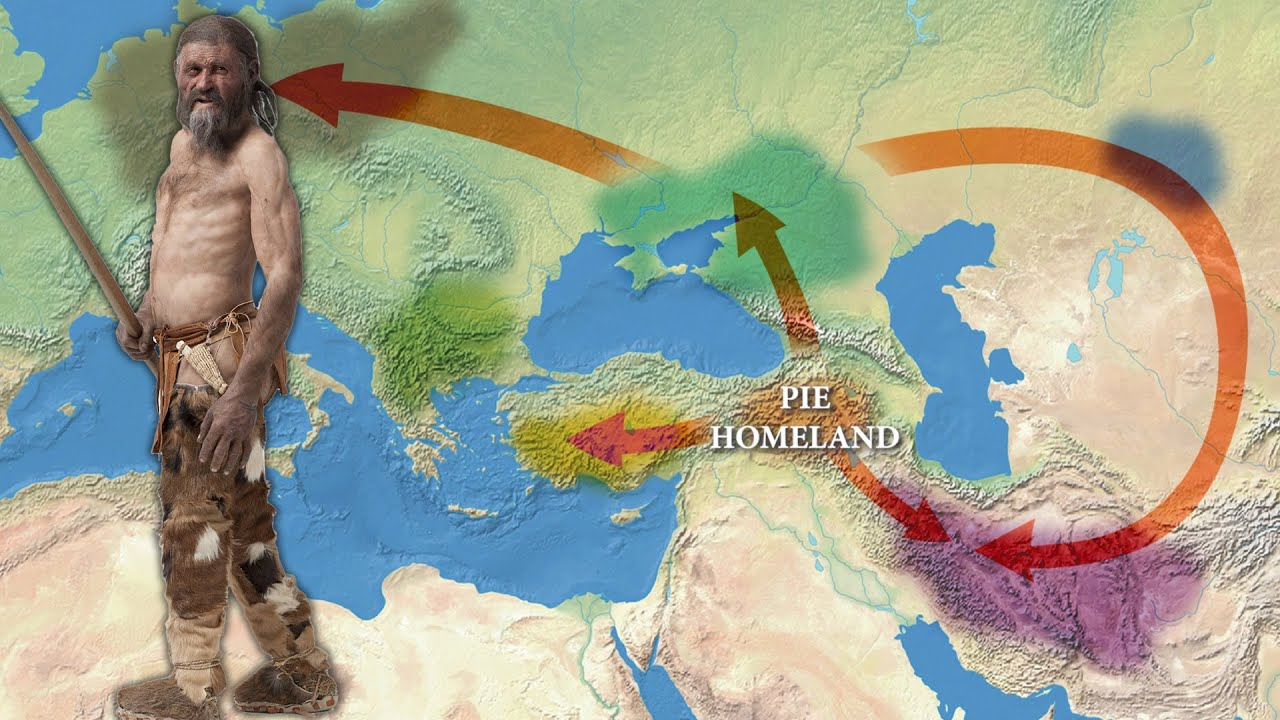

Ötzi belonged to the haplogroup G, the sub category G-L9, Parson explained adding that haplogroup G suggests that earlier people migrated to the Ötztal valley from Fließm — a municipality in western Austria founded in the sixth century.

The researchers were able to positively identify 19 men who have the same ancestry as Ötzi. But the surprising discovery has yet to be revealed to those most closely affected by it. The 19 men have not yet been informed of the results and it is not known whether the researchers will do so.

Most people can trace their family tree back at least a few generations, while the more serious ones are able to accomplish many centuries. But imagine being able to trace your lineage back to a 5,300-year-old mummy. That is exactly what has happened after scientists performed DNA tests on ‘Ötzi the Iceman’ and found 19 living…