Archaeological and Linguistic Significance

The discovery and ongoing study of these tablets, initiated by H. Winckler together with Greek-Ottoman archeologist Theodore Makridi Bey, from 1906 to 1912, have significantly advanced our understanding of the Hittite civilization and its interactions with neighboring cultures. The linguistic findings, in particular, have revolutionized Indo-European studies, revealing previously unknown languages and dialects within this family.

The Linguistic Landscape of the Boğazköy Archive

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Boğazköy Archive is its linguistic diversity, which encompasses texts in eight different languages. This polyglot nature highlights the cultural and political influence of the Hittite Empire.

1. Cuneiform Hittite: The role of Cuneiform Hittite in the Hittite Empire cannot be overstated. As the predominant language of the Boğazköy Archive, it offers a direct insight into the administrative, legal, and diplomatic workings of the empire. This version of the cuneiform script, adapted from the earlier Akkadian system, was a vital tool for recording laws, treaties, and royal decrees, serving as the backbone of governance and order in the Hittite state. Its use in diplomatic correspondence, especially in treaties such as the Treaty of Quadesh, underscores its significance as a language of international relations in the ancient Near East.

2. Akkadian: Serving as one of the main languages of the archive, these represent the administrative and diplomatic lingua franca of the ancient Near East. Akkadian, an ancient Semitic language, originated in Mesopotamia around 2500 BC and was extensively used for administration, diplomacy, and literature. Akkadian is divided into two major dialects: Assyrian and Babylonian. It was written using the cuneiform script and is of great historical significance, providing insights into ancient Mesopotamian civilization and culture. Akkadian's influence declined around the 1st millennium BC but left a lasting impact on subsequent languages in the region.

3. Sumerian: A dead language by 1200 B.C., Sumerian's inclusion indicates its continued scholarly significance. The ancient non-Indo-European language of the Sumerian civilization was the first to develop the cuneiform script, which, although already dead at that time, was still being taught.

4. Hurrian: Neither Indo-European nor Semitic, Hurrian reflects Mitanni's influence on the Hittite Empire. It was the language of the Land of the Mitanni, to the east of the Hittite Empire, a significant cultural and political group in the region encompassing parts of modern-day Turkey, Syria, and Iraq. The language is known from texts dating from around 2300 BC to the first century AD. Hurrian played a crucial role in the cultural and political tapestry of the area, especially in the context of its interactions with neighboring civilizations like the Hittites and Assyrians. The language's structure and vocabulary remain a subject of study for linguists, offering insights into the diverse linguistic landscape of the ancient Near East.

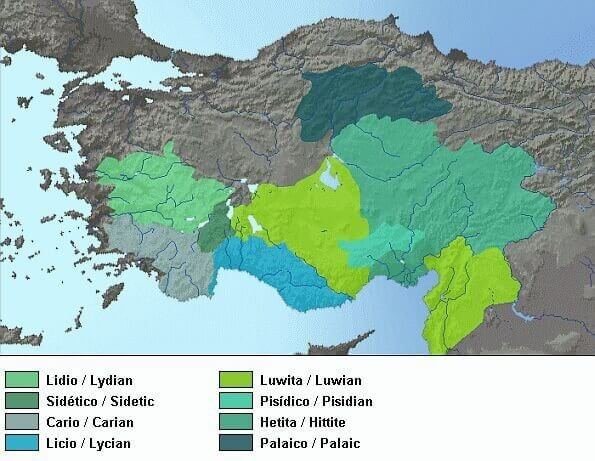

5. Luwian: An Anatolian Indo-European language probably spoken in western Anatolia, closely related to Hittite and possibly a precursor to Lycian. The Luwian language, part of the Anatolian branch of the Indo-European family, played a crucial role in the geopolitical dynamics between the Hittite Empire and the independent states of western Anatolia during the Bronze Age. As a language closely related to Hittite, Luwian served as a linguistic bridge, facilitating diplomatic and cultural exchanges between the Hittites and their western neighbors. The presence of Luwian in the Boğazköy Archive, especially in texts related to western regions, indicates its importance in maintaining relationships and asserting influence over these independent states. Luwian's use in regional administrative and diplomatic documents reflects its status as a regional lingua franca, essential for the negotiation of treaties, trade agreements, and alliances.

6. Palaic: Palaic, an ancient Indo-European language, was one of the lesser-known members of the Anatolian language family, alongside Hittite and Luwian. It was primarily spoken in the region of Pala in north-central Anatolia, now part of modern Turkey. Known mainly from cuneiform tablets of the Boğazköy Archive, Palaic's use seems to have been largely religious, dedicated to ritual and liturgical texts. The language provides a glimpse into the linguistic diversity of ancient Anatolia and the religious practices of its people, but much about Palaic remains obscure due to the limited number of texts available.

7. Hattic (Proto-Hittite): A non-Indo-European language, mainly used in ritual texts, offers a window into the religious practices and beliefs of the Hittites. It was primarily used by the Hattians, indigenous inhabitants of central Anatolia. Primarily known from Hittite texts where it is used in religious contexts, Hattic is distinctive for its unique vocabulary and structure, differing significantly from the surrounding Indo-European languages. Despite its limited corpus, Hattic is crucial for understanding the cultural and linguistic prehistory of Anatolia.

8. An Unidentified Language: The eighth language, which is different from the others, has not yet been precisely identified. The only evidence we have is that it contains some Indo-European terms that correspond to a treatise on equestrian art written in Hittite by Kikkuli, a Hurrian from the Land of the Mitanni. There is a possibility that this is the new Anatolian language that linguists have identified as Kalasma.