A remarkable book, the oldest surviving manuscript of Claudius Ptolemy's Geography, was recently brought out of the Vatopedi Monastery on Mount Athos and made its debut in Cyprus. It was presented at the exhibition Cyprus Island – History – Memory – Reality, organized by the Cultural Foundation of the Bank of Cyprus in Nicosia. The exhibition offers a modern and interactive portrayal of life in Cyprus from ancient times to the present, with a central message about the island's unbreakable unity.

"By focusing on time, place, and people, relationships emerge and narratives are formed that highlight aspects of Cyprus' history and contemporary reality, which have contributed to shaping the unified Cypriot island identity," said Yiannis Toumantzis, director of the Cultural Foundation of the Bank of Cyprus and the first Deputy Minister of Culture of Cyprus. He, along with Dimitra Ignatiou, curated this unique exhibition. Interestingly, the original plan was for the exhibition to remain open until June, but due to its immense popularity, it has been extended until early 2026, as predicted by the President of the Republic of Cyprus, Nikos Christodoulides, during the opening ceremony.

When Ptolemy Depicted the Geography of the Greek World

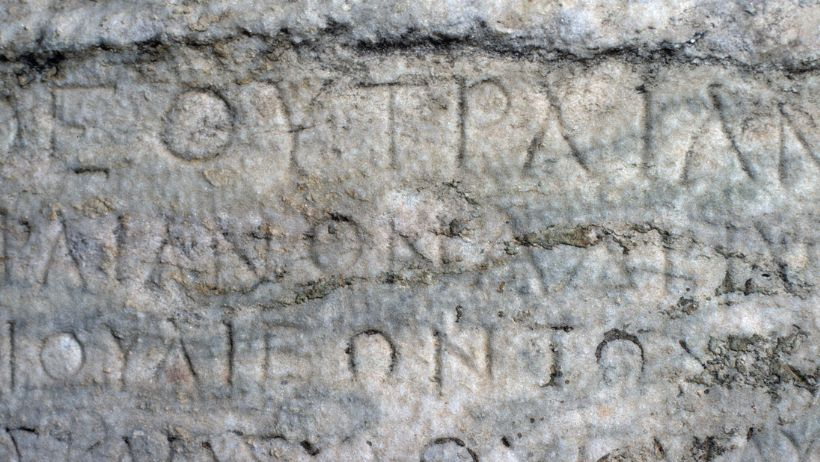

The Vatopedi manuscript, known as Codex 655, consists of 296 parchment leaves, dates back to the 13th century, and is part of a small group of surviving secular manuscripts kept in the libraries of Mount Athos monasteries. Undoubtedly, it is one of the rarest manuscripts stored on the Holy Mountain.

The manuscript includes Ptolemy's Geographical Synopsis, the famous Greek philosopher and naturalist who lived in Alexandria during 127-151 AD, Strabo's Geographica and his Chrestomathy from the Geographical. Many of the texts in the manuscript are copies of other manuscripts, following lost originals.

The Ptolemaic Maps of the Known World

According to archaeologist Dimitris Liakos from the Department of Antiquities of Halkidiki and Mount Athos, "The most impressive and noteworthy element of the manuscript is the maps from the 8th book of Geographical Synopsis, each depicting one or more countries from the known world of the 2nd century AD. The first map is of the Oikoumene (the known world), followed by 10 maps of Europe, four of Africa, and twelve of Asia. Of the 27 bifolium maps that were originally included in the manuscript, 24 are still intact, and three are half-preserved, as they were later detached in various ways." Ptolemy's Geography collected all the geographical knowledge of his time and enriched it with nautical descriptions, offering a relatively accurate portrayal of Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and the Arabian Peninsula. Among these is one of the earliest cartographic depictions of Cyprus, a martyr island.

The Vatopedi manuscript was created between the late 13th and early 14th centuries, and the 42 maps are so meticulously drawn that they allow for the identification of mountains, plains, seas, and a vast number of place names. A second, similar manuscript was created in the 15th century for Cardinal Bessarion and is now held at the Marciana Library in Venice.

A Manuscript with a Rich History

The manuscript has a unique history. It was most likely created in Constantinople by two scribes and, according to scholars, circulated in "high spiritual circles and scholarly circles." It reached the Athonite community after the Fall of Constantinople. In 1841, Minas Minoyidis, a representative of the Greek Enlightenment, acquired seven original leaves and sold them to the National Library of Paris. A few years later, in 1853, the paleographer and calligrapher Konstantinos Simoniadis sold another 21 leaves to the British Museum. It has since been confirmed that six more leaves are missing, believed to be entirely lost.

For the Vatopedi Monastery, the manuscript is a significant historical treasure. During his recent visit to Nicosia, Abbot Ephraim of the monastery presented the manuscript, which contains one of the earliest depictions of Cyprus, along with other invaluable ecclesiastical, Byzantine, and post-Byzantine treasures, such as monumental paintings, portable icons, ecclesiastical silverware, manuscripts, and rare prints. He highlighted the monastery's historical ties to Cyprus.

The Manuscript's Return to Mount Athos

Last week, the precious manuscript returned to Mount Athos—it had been transferred to Cyprus for the first phase of the exhibition, and for reasons of protection and security, it could not stay longer. The head of the Department of Antiquities of Halkidiki and Mount Athos, Giorgos Skiadaresis, archaeologist Dimitris Liakos, and conservator Athanasios Chouhoutas traveled to Nicosia to carefully arrange the valuable exhibit, which was then handed over to Abbot Ephraim by Christodoulos Chatzichristodoulou, the director of the Cultural Foundation of the Bank of Cyprus.

An Exhibition in Five Acts

The exhibition organized by the Cultural Foundation of the Bank of Cyprus is structured into five sections and is organized in celebration of the Foundation's 40th anniversary and the 50th anniversary of the Turkish invasion. Through artifacts and rare archival material from the Foundation's collections and private sources, the history of Cyprus is depicted from antiquity to the present. The exhibition also highlights the continuities and discontinuities that emerge and are absorbed over time in Cyprus's historical path, sometimes dominating and other times fading from historical memory.

One section of the exhibition is dedicated to the "difficult years" of the Cyprus Republic, from 1963–1964 to the tragic consequences of the 1974 Turkish invasion. The exhibits include antiquities, folk culture objects, works of contemporary art, historical maps, rare editions, manuscripts, engravings, printed and digital archival material, as well as digital applications.

The exhibition is accompanied by a special publication and parallel activities such as roundtable discussions, experiential educational programs, lectures, guided tours, presentations, and specially designed activities based on the sensory museum program "Sensations" of the Cultural Foundation for people with disabilities.