For centuries, Indigenous peoples living near Earth’s polar regions passed down legends, beliefs, and superstitions about the aurora borealis, also known as the Northern Lights.

To the Sámi people of Scandinavia, the lights were a source of awe and fear. Elders warned children never to disturb them, lest they be swept up into the sky. The Inuit of Greenland believed the aurora was a pathway to the heavens, where the spirits of the dead played ball with a walrus skull. In Finland, some believed Arctic foxes were responsible—running so fast across the mountaintops that their tails sent up sparks that lit the night sky.

But beyond myth and metaphor, there was one striking belief that united many of these cultures:

They claimed they could hear the lights.

Reports spoke of crackling, popping, and even a soft rustling sound, like rain falling from above.

As the Danish explorer Knud Rasmussen noted in 1932, one Greenlander told him the sound was made by "the souls running across the frozen sky."

Science Used to Say It Was Impossible

For decades, scientists dismissed the idea. The aurora occurs between 60 and 200 miles above Earth, in the ionosphere—a region so thin that it can’t effectively carry sound waves. Even if the lights somehow did make noise, it was believed the sound would dissipate long before reaching the ground.

So when people described hearing crackling or humming under the shimmering sky, researchers assumed it was either a psychological phenomenon or wishful imagination.

New Research Suggests Otherwise

But recent studies are challenging that skepticism.

Unto Kalervo Laine, a professor at Aalto University in Finland, once rejected the idea himself. However, in 2000, he and his team began investigating the ancient accounts, aiming to make sense of this seemingly impossible phenomenon.

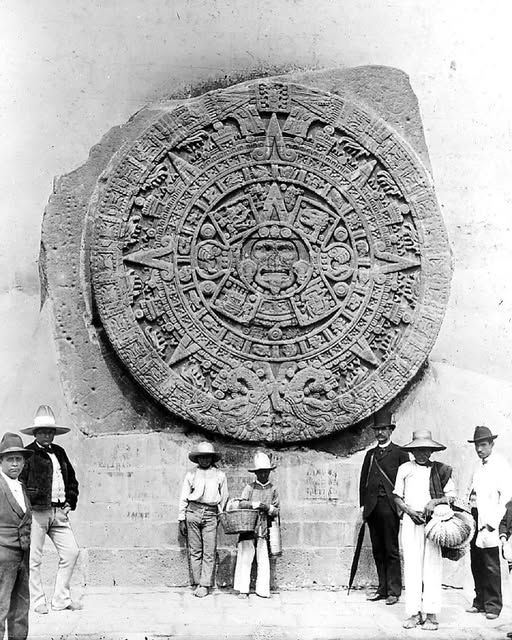

Auroras occur when solar winds carry high-speed particles from the sun toward Earth, guided by our planet’s magnetic fields. These energetic particles collide with atoms in the upper atmosphere, creating dazzling displays of light around the magnetic poles.

But Laine’s theory takes us closer to the ground.

He explains that during auroral activity, a temperature inversion layer may form closer to Earth’s surface. In this layer, warm air traps cooler air underneath—along with negatively charged particles. These charges build up beneath a layer of positively charged particles.

Then, during an aurora event, a magnetic pulse may trigger a sudden discharge—producing the very crackling or popping sounds described in ancient lore.

Echoes of the Past, Confirmed by Science

This theory would explain why the sounds often occur at the same time as the lights and why generations of people believed they were hearing the sky itself "speaking" during these celestial events.

So while solar storms may trigger the aurora borealis, the ancient people weren’t imagining things when they said the lights could be heard.

As it turns out, those old legends weren’t just stories—they were science, waiting to be understood.