A groundbreaking genetic study of Neolithic remains from Çatalhöyük, one of the earliest known cities in the world, is challenging long-held assumptions about ancient social structures. The analysis suggests that female lineage played a central role in household formation—hinting at a matrilocal or even matrilineal society nearly 9,000 years ago.

Life in Neolithic Anatolia

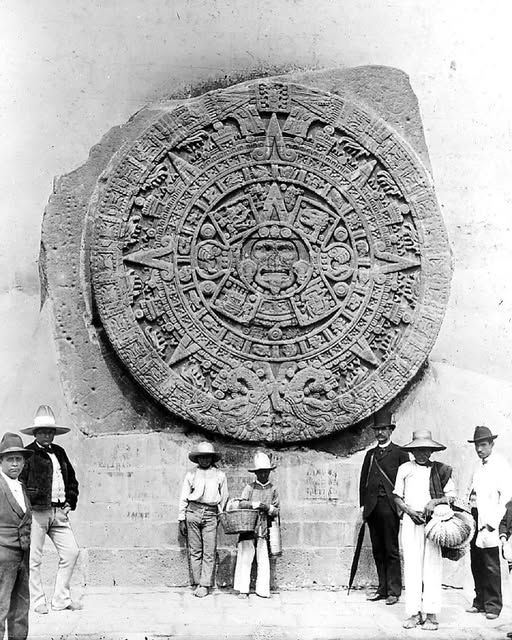

Located in central Turkey near modern-day Konya, Çatalhöyük thrived between 7100–5500 BCE. The site is famed for its densely packed mudbrick homes and rich archaeological layers—each house built atop the ruins of the previous. The community's dead were buried beneath their floors, giving researchers a direct window into the social fabric of this ancient world.

The Big DNA Breakthrough

In a collaborative international project, scientists examined the DNA of 131 individuals buried at Çatalhöyük. Using advanced analysis of the petrous bone—a dense part of the skull ideal for DNA preservation—they discovered something striking: people buried in the same house were more closely related through the maternal line than the paternal.

“This suggests that women were more important in forming households,” says Dr. Eva Rosenstock from the University of Bonn.

In other words, it appears that people lived in matrilocal households, where women stayed put and men possibly moved in—a setup radically different from the later patriarchal norms that would dominate much of Eurasian history.

Not Quite a Matriarchy—but Close?

While the researchers stop short of calling Çatalhöyük a true matriarchy—where women held political or institutional power—there are plenty of signs suggesting high female status. Women were buried with richer grave goods, and early excavators like James Mellaart noted the abundance of female figurines at the site, long speculated to indicate goddess worship or female-centered rituals.

“It’s not a matriarchy in the classic sense,” Rosenstock clarifies, “but the archaeological and genetic evidence points to women having a central social role.”

Two Infants, One House, No Kinship

Among the key findings were two newborn skeletons excavated from the West Mound. Though found buried beneath the same home, genetic analysis showed they weren’t closely related. This reinforces earlier theories that Çatalhöyük’s households weren’t based purely on blood ties, but perhaps on shared economic, cultural, or spiritual bonds.

Continuity and Change: East and West Mounds

For decades, scholars believed there was a cultural break between Çatalhöyük’s East and West Mounds. But the genetic similarities between the two infant skeletons and older East Mound remains suggest otherwise. “It’s strong evidence of cultural and genetic continuity,” says Rosenstock.

So why was there a brief disruption around 6000 BCE when the West Mound was first built? That mystery remains unsolved.

Why It Matters

This study adds fresh weight to an ongoing academic debate: Were ancient societies more gender-balanced—or even women-led—before the rise of patriarchal institutions? While Çatalhöyük may not have been a full-fledged matriarchy, it clearly operated on very different social principles than most of the ancient and modern world.

It also opens up new questions:

When did the shift to male-dominated structures happen across Europe and the Near East?

How did kinship systems evolve alongside agriculture, property, and inheritance?

And how many more clues are buried—quite literally—beneath our feet?

As scientific methods like archaeogenetics continue to evolve, so too does our understanding of who we are—and who we were.