A five-month-long excavation in southeastern France has revealed a remarkable archaeological site featuring rock-hewn dwellings, an elaborate polychrome mosaic, Late Roman tombs, and a sophisticated drainage system—all of which offer new insight into ancient craftsmanship and urban design.

Archaeologists from France’s National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP) conducted the excavation on the slopes overlooking Alès, a city in the Occitanie region. Their findings point to continuous human occupation at the site from the 2nd to the 6th century CE, during the Gallo-Roman period.

Homes Carved Into the Hillside

The excavation, which covered an area of 3,750 square meters in the L’Hermitage district, uncovered at least four ancient homes partially carved directly into the rock. The inner walls were lined with clay coatings to prevent rainwater from seeping in through the limestone bedrock—an early example of passive water management.

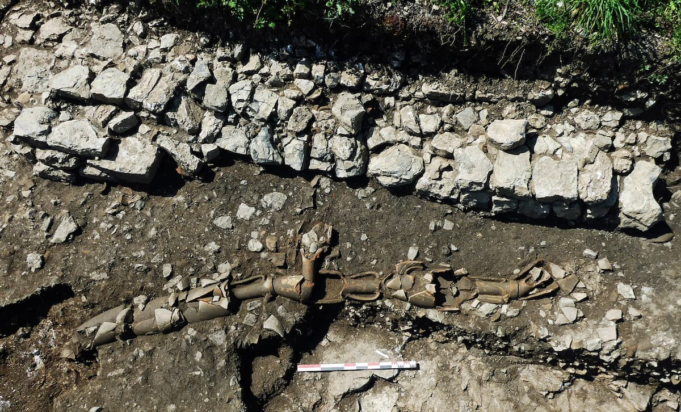

The drainage system beneath these homes was equally impressive: built using repurposed roof tiles and bricks, the network efficiently channeled water away, showcasing a deep understanding of hydraulic and architectural engineering in antiquity.

A Masterpiece in Stone and Color

The most striking discovery was a 750-square-meter structure that had undergone at least two major renovations. Initially featuring an earthen floor, the house was later upgraded with cement-based flooring and mosaic panels—testifying to the elevated status of its occupants.

In a room measuring 4.5 by 3.8 meters, archaeologists revealed a well-preserved mosaic floor. At its center: intricate interlaced geometric patterns in black and white tesserae, accented with rare purple-red tones—likely derived from vermilion, a mercury-based mineral pigment reserved for the elite.

Even rarer were yellow tesserae, which further underscore the artistic sophistication and uniqueness of the piece. Some parts of the floor remained plain white, possibly to accommodate furniture or storage benches, while a bordering motif of white crosses on black may mark passageways to other rooms.

Researchers are now examining whether the building was a Roman domus—a type of upper-class urban home characteristic of the Roman Empire.

A Clever Clay Jar Drainage System

On the building’s eastern side, a particularly ingenious sewage system was discovered. Made from a sequence of amphorae (ceramic storage jars) with their bases removed and necks fitted together, the system drained rainwater from the roof outward—an innovative use of available materials for environmental control.

A Silent Necropolis

To the south of the site, archaeologists unearthed a Late Roman necropolis (5th–6th century CE), with at least ten tombs. The deceased were interred facing west, likely in wooden coffins that have since decomposed. Some tombs were covered with stone slabs, but grave goods were rare.

Two isolated burials to the northwest appear to belong to the same era, though radiocarbon dating will help refine their timeline.

Layers of History Above and Below

Between the 16th and 18th centuries, the landscape was reshaped into agricultural terraces, and in the 19th century, the land was again altered—explaining the overlying deposits that preserved these ancient layers.

The discovery reinforces Alès’s importance as a continuously inhabited settlement since antiquity and showcases the advanced technical skill and aesthetic sensibility of its ancient inhabitants.

The mosaic, in particular, stands out as one of the most significant archaeological finds in the region in decades, offering a vibrant glimpse into domestic life and artistic expression in Roman Gaul.