A recent discussion at the Acropolis Museum shed light on a lesser-known chapter in 19th-century Athenian history, sparked by Dimitris N. Karydis’s compelling study “Schinkel in Athens.”

In 1833, Athens was a small town of just 10,000 people—a mosaic of ancient ruins, Byzantine churches, and Ottoman bazaars. Despite its modest size, it was declared the capital of the newly formed Greek state, largely due to its historical and symbolic significance in antiquity.

But this symbolic city needed a serious makeover. If Athens was to function as a modern European capital, it had to be drastically restructured. At the heart of this transformation lay one crucial decision: where to place the new royal palace for King Otto I of Greece.

“Between 1833 and 1835, what had been a mostly rural town—with its markets, mosques, ancient remains, and Byzantine churches,” writes architect and urban planner Dimitris N. Karydis in his book Schinkel in Athens (published in English by Archeopress), “was transformed into a modern, European-style city. Straight boulevards were drawn, and an imported monarch ruled ‘by the grace of God.’ In other words, while the city was changing, the Greek people had no real say in the making of their own state.”

Karydis’s research served as the catalyst for an engaging roundtable held at the Acropolis Museum auditorium. The discussion brought together five prominent scholars to explore Athens’s architectural evolution, the ideology behind its urban planning, and how 19th-century visions still shape perceptions of the city today.

An Academic Gathering at the Foot of the Parthenon

The event featured Cambridge archaeologist Elizabeth Key Fowden; NTUA professors Kostas Tsiambas and Ariadni Vozani; and architect and theorist Leon Krier, a prominent voice in New Urbanism. Together, they delved into the tensions between ancient legacy and modern vision, symbolic power and architectural ideology.

Karydis’s book challenges prevailing narratives about who truly shaped the city’s first urban masterplan. At the center of this reimagining is a figure who never even set foot in Athens—Prussian architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel.

A “Daring Utopia” on the Sacred Hill

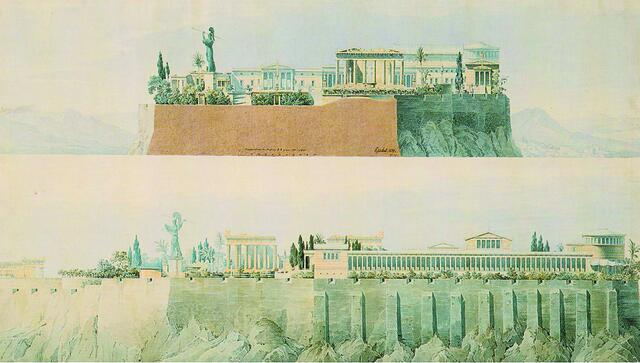

Professor Ariadni Vozani highlighted Schinkel’s controversial proposal: building King Otto’s palace on top of the Acropolis itself. Though the design was never realized, it reflected bold ambitions for the Greek capital’s identity.

“Schinkel was the quintessential Renaissance man,” Vozani noted. “An architect, urban planner, painter, furniture designer, and even a stage set designer. He imagined a new Athens he would never see.”

According to Vozani, the palace-on-the-Acropolis idea belonged to the realm of daring utopia. “It was clearly intended to reassert the dominance of the Acropolis over the city—not just physically, but symbolically. In this new Athens, the Acropolis was once again ‘center stage.’ It became the city’s focal point, the object of collective desire. It’s still the one landmark we all try to glimpse from anywhere in town—and, conversely, the one that seems to watch over all of Athens.”

She continued:

“Schinkel embodies the spirit of a time torn between romantic nostalgia and revolutionary ambition. His palace proposal emerged from a correspondence with Prince Maximilian of Bavaria, exploring what ideal architecture should look like—and specifically, how the grandeur of classical Greek architecture could inspire a new regime.”

While the project never materialized, it revealed a deeper ideological stance. Schinkel’s vision reflected the desire for continuity—the idea that the sacred hill had been inhabited for millennia and should remain so, under new rulers. That vision stood in stark contrast to the one that ultimately prevailed: “cleansing” the Acropolis of all post-classical layers, including Byzantine and Ottoman-era constructions.

Though long dismissed as fantastical, Schinkel’s utopia still stirs debate today—especially as we continue to negotiate the balance between preservation and modernization, national identity and global influence, memory and myth.