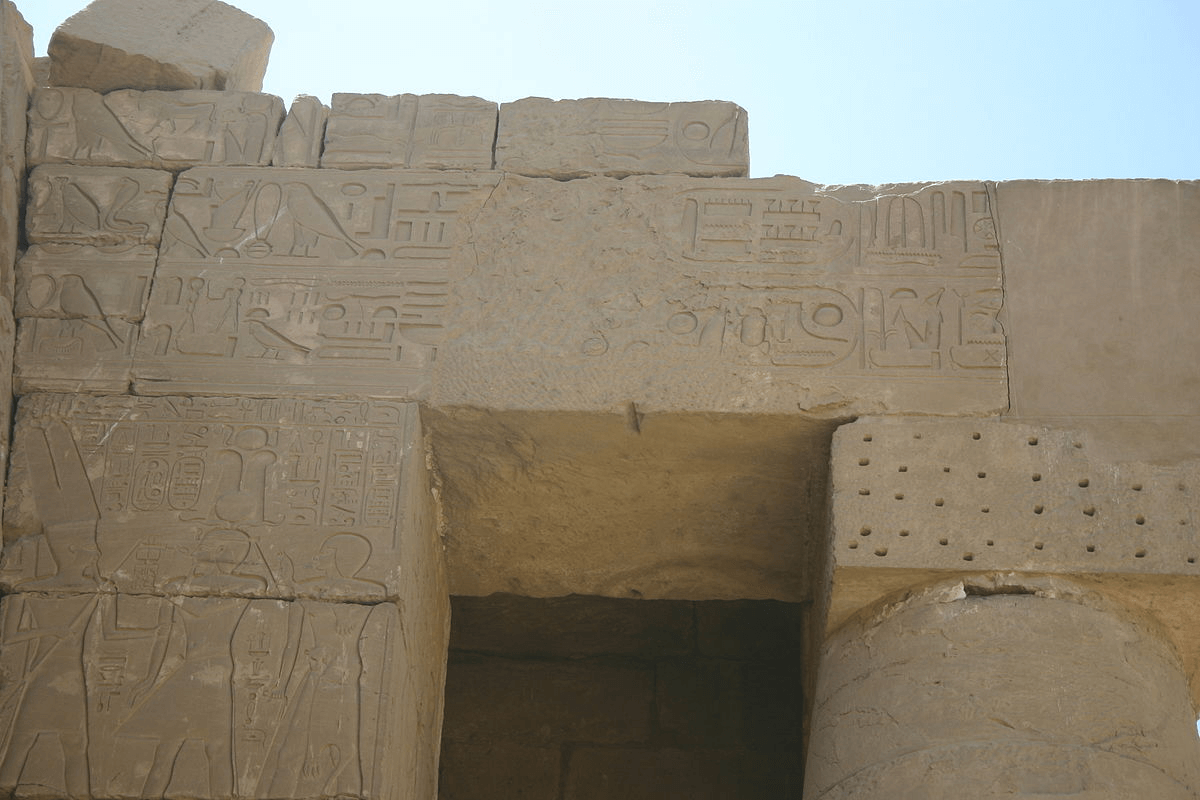

While southern kings are ruling during Dynasty XXI, we have the kings in the north who are also kings of Egypt, the official kings. Ramses XI dies, and Smendes takes over. He is a military man who declares himself king. Now what does he do? First, he moves the capital. He moved the capital from that biblical city that Ramses created Pi-Ramses, to another site in the Delta, Tanis. He causes a problem for archaeologists with this move.

Dynasty XXI, Smendes and New Capital

When he moves, he takes with them the large statues of Ramses the Great that Ramses had built for his biblical city. He takes with them the obelisks that Ramses had erected there. And he brings them to his new capital. So this is kind of like a ready-made, pre-fabricated city.

When he dies, he is followed by a pharaoh named Amenemnisu. The name isn’t important. What’s really important is, whose son is he? Heri-Hor, the high priest of Thebes, started it all in the south by writing his name in a cartouche. This shows that Thebes in the south and this new dynasty at Tanis in the north are cooperating. After his death, Amenemnisu is followed by Psusennes I.

How Did Psusennes End Up Getting Merneptah’s Sarcophagus?

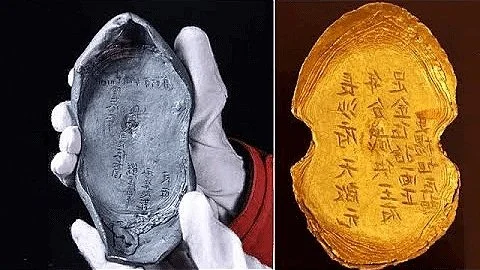

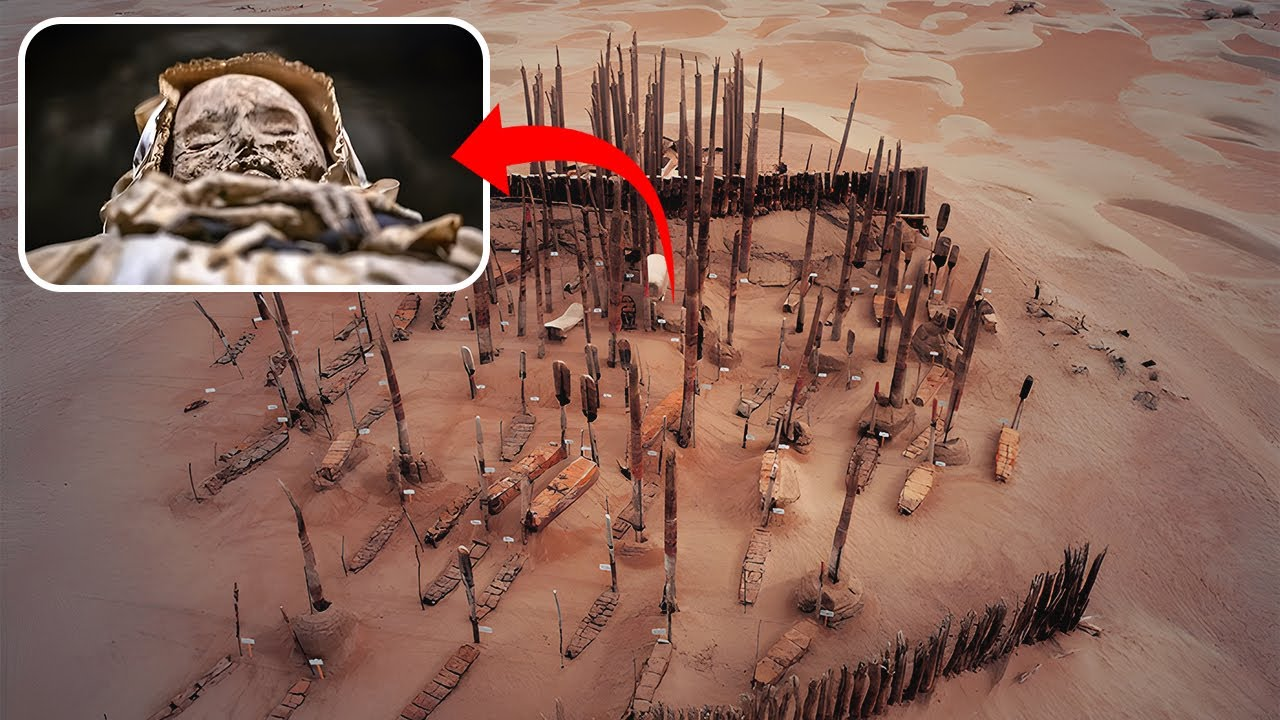

The tomb of Psusennes I was found intact. It rivaled Tutankhamen. He’s buried at Tanis. His new capital. He was buried in a big pink Aswan granite sarcophagus. The lid to that sarcophagus was Merneptah’s, the 13th son of Ramses the Great, who became king.

Inside that sarcophagus with Merneptah’s lid was another stone sarcophagus—black granite. Inside that was another alabaster one. Inside that was a solid silver coffin. Inside that silver coffin was the badly damaged body of the pharaoh. But the face of the pharaoh was covered with a gold mask. Silver was more valuable than gold in Egypt—about three times. Everybody makes a big deal out of Tutankhamun’s gold coffin.

But how did he wind up with Merneptah’s sarcophagus lid? Well, remember the Deir el Bahri cache, when all the mummies were brought together by the high priest and moved for safety? That was not the only time that happened. Not the only time that royal mummies came together to be moved. There was another time. And this was another discovery of royal mummies. Now, in this royal cache is Amenhotep III, one of Egypt’s greatest. Also in this cache is the mummy of Ramses the Great’s 13th son, Merneptah, who became king of Egypt.

When the high priests are doing these inventories of the Valley of the Kings, they discover the tombs have been plundered, and they move the mummies to safe places. One place is Deir el Bahri. Another is the tomb of Amenhotep II. They’re going to put all the royal pharaohs in this side chamber, brick it up, and hope you can protect that one. And it worked. They stayed protected.

They’re bringing Merneptah out of his original tomb. He’s buried in this huge sarcophagus. Pink Aswan granite. They’re not going to drag that to the tomb of Amenhotep II because everybody will see. So they leave the sarcophagus behind. And they bury the mummy of Merneptah.

The sarcophagus and lid are shipped north to Tanis for Psusennes to be buried in, and that’s how a king in Tanis comes to be buried with the lid of a pharaoh buried in the Valley of the Kings. It was a cooperation between the people in the south in Thebes and the kings who were ruling in the north.

What Happened after Psusennes I?

Anyway, these kings were not poor. Amenemope, Psusennes’s son, was buried at Tanis also. He, too, had a gold face mask. There are other kings of this dynasty. There’s Siamun. Siamun is interesting. He builds at Tanis, a sign that he’s got money. Wealth. He builds a temple to Amun, the principal god of Thebes. In a sense, Tanis is mirroring the religious capital at Thebes because the chief god in Thebes is Amun. And Siamun’s building a temple to Amun at Tanis.

During Siamun’s reign, princesses of Egypt got married out. For the first time, kings of Egypt sent their daughters out to marry foreigners.

For example, in the Bible, in Kings I we’ve got a story of Hadad, who was an Edomite who fled to Egypt. What we’re told is Hadad became a great favorite of pharaoh, who gave him his own wife’s sister, the sister of the “Great Lady”, in marriage. “Great Lady” is the translation of hemet weret, “the great wife.”

This is a big deal, because she is eventually going to leave the country with her husband. And to send an Egyptian out of the country was not at not an easy thing to do. David’s son, King Solomon, also marries an Egyptian princess. So what we have here is a reversal of power. Egypt’s princesses are going out of Egypt, whereas in the old days, you had the foreign ones coming in for the king of Egypt to marry.

Common Questions about What Happened to Dynasty XXI after Ramses XI

Q: How did Dynasty XXI kings in the north and south cooperate after Ramses XI had died?

Smendes is the one who ascends the throne after the death of Ramses XI. He moves the capital to Tanis during his reign. After Smendes, Amenemnisu, the son of Heri-Hor, becomes king. A king from the south moves to the north to rule. This can serve as an example of cooperation between the southern and northern kings of the Dynasty XXI.

Q: During Dynasty XXI era, why was the sarcophagus of Merneptah not taken to the tomb of Amenhotep II?

When transferring the mummies of the pharaohs to the tomb of Amenhotep II the high priests of the Dynasty XXI left Merneptah’s sarcophagus. They did this to avoid unnecessary attention. After the transfer of the mummies, the sarcophagus was shipped to the north and used in the burial of Psusennes I.

Q: What makes the burial of Psusennes I, the Dynasty XXI northern king, distinctive?

Psusennes I has one of the most remarkable burials of Dynasty XXI. First, he had Merneptah’s pink Sarcophagus when he was buried. In addition, his silver coffin, which surpassed the gold coffin of Tutankhamun in value, shows how wealthy the king was.