From the 3rd century BC onwards, Greek inventors and engineers revolutionized various aspects of daily life, from transportation and construction to timekeeping and warfare. The legacy of Greek ingenuity endures through numerous inventions and discoveries that continue to shape modern society.bold the invention

Archimedes' screw: The Archimedes' screw, dating back to the 3rd century BC, is attributed to the Greek mathematician Archimedes of Syracuse. This ingenious device was designed for lifting solid or liquid substances from a lower plane to a higher elevation. Its simple yet effective mechanism has been utilized for various applications, including irrigation and drainage systems, showcasing ancient Greek engineering prowess.

Streets: Ancient Greek innovation in urban planning is exemplified by the development of streets, such as the Porta Rosa in Elea, Italy, dating from the 4th to 3rd centuries BC. These streets were meticulously designed, featuring limestone blocks and drainage systems to manage rainwater. The Porta Rosa stands as a testament to the advanced infrastructure and architectural achievements of ancient Greek civilizations.

Cartography: The Greeks made significant contributions to cartography, with the first widespread amalgamation of geographical maps attributed to Anaximander around the 6th century BC. While influenced by Near Eastern practices, Anaximander's maps marked a milestone in geographic knowledge, laying the foundation for future advancements in navigation and exploration.

Rutway: Dating back to around 600 BC, the Diolkos represented an early form of railway developed by the Greeks. Stretching over 6 to 8.5 kilometers, this rudimentary transportation system facilitated the movement of goods and people overland, showcasing the Greeks' innovative approach to infrastructure and logistics.

Differential gears: The Antikythera mechanism, dating from the 1st century BC, employed a sophisticated differential gear system for astronomical calculations. This remarkable device, discovered in a Roman-era shipwreck, demonstrated the Greeks' advanced understanding of mechanics and their ability to apply it to practical inventions with astronomical implications.

Caliper: The earliest example of a caliper, featuring a movable jaw, was found in the Giglio wreck near the Italian coast and dates back to the 6th century BC. This precision measuring tool highlights the Greeks' emphasis on accuracy and craftsmanship in various fields, including engineering, architecture, and scientific inquiry.

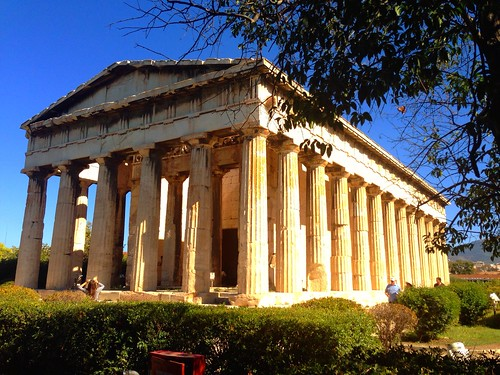

Truss roof: Invented around 550 BC, the truss roof represented a significant advancement in architectural engineering. Utilized in various structures, including temples and public buildings, the truss roof demonstrated the Greeks' mastery of structural design and their ability to create durable and aesthetically pleasing architectural features.

Cranes: Dating back to approximately 515 BC, the crane was a labor-saving device that revolutionized construction practices in ancient Greece. By enabling the efficient movement of heavy materials and facilitating the assembly of monumental structures, such as temples and theaters, cranes played a pivotal role in shaping the architectural landscape of ancient Greek cities.

Escapement: Described by the Greek engineer Philo of Byzantium in the 3rd century BC, the escapement mechanism was integrated into various devices, including washstand automatons. This innovative component, which regulated the movement of machinery, foreshadowed the development of mechanical clocks and other timekeeping devices in later centuries.

Tumbler lock: Introduced in Greece around the 5th century BC, the tumbler lock represented a significant advancement in security technology. This mechanical device, featuring tumblers that must be aligned to open the lock, provided enhanced protection for valuable assets and contributed to the development of modern lock mechanisms.

Gears: The development of gears in ancient Greece, dating back to the 5th century BC, marked a pivotal moment in mechanical engineering. These intricate mechanisms, refined over time, found applications in various practical devices, including mills, clocks, and even early forms of automation. The Greeks' mastery of gear technology laid the groundwork for subsequent advancements in machinery and manufacturing processes.

Plumbing: Dating to around the 5th century BC, the ancient Greek civilization, particularly the Minoan civilization of Crete, pioneered the use of underground clay pipes for sanitation and water supply. Excavations in sites such as Olympus and Athens revealed extensive plumbing systems, including baths, fountains, and domestic water distribution networks, showcasing the Greeks' ingenuity in urban infrastructure.

Spiral staircase: The earliest spiral staircases, dating from 480 to 470 BC, appeared in Temple A in Selinunte, Sicily. These architectural marvels provided access to upper levels of structures while conserving space and exemplifying the Greeks' innovative approach to design and construction. Spiral staircases became iconic features of ancient Greek architecture, admired for their elegance and functionality.

Urban planning: Miletus, one of the first known towns with a grid-like plan for residential and public areas, exemplified the Greeks' advancements in urban planning around the 5th century BC. Through innovations in surveying and city layout, the Greeks created organized and efficient urban environments that influenced subsequent civilizations' approaches to city design and management.

Winch: The earliest literary reference to a winch dates back to the 5th century BC in Herodotus' account of the Persian Wars. By the 4th century BC, winches and pulley hoists became common tools for architectural and construction purposes, enabling the Greeks to lift heavy loads with ease and precision. The widespread adoption of winch technology revolutionized construction practices and contributed to the development of monumental structures.

Showers: Around the 4th century BC, ancient Greeks constructed shower rooms for athletes, depicting plumbed-in water systems on Athenian vases. These early examples of shower-baths provided comfort and hygiene to users and reflected the Greeks' emphasis on personal grooming and cleanliness. The integration of showers into public and private spaces exemplified the Greeks' advancements in plumbing and water management technology.

Central heating: The Great Temple of Ephesus, built around 350 BC, featured an innovative central heating system that circulated heated air through flues laid on the floor. This early form of central heating provided warmth and comfort to occupants, demonstrating the Greeks' ingenuity in architectural engineering and environmental control systems.

Lead sheathing: Around 350 BC, Greeks employed lead sheathing to protect ship hulls from marine organisms, as evidenced by the Kyrenia ship. This early use of lead as a protective material showcased the Greeks' understanding of metallurgy and their ability to innovate in maritime technology to improve vessel durability and longevity.

Canal lock: The construction of canal locks, such as those built into the Ancient Suez Canal under Ptolemy II in the early 3rd century BC, revolutionized waterway transportation. These engineering marvels allowed for the efficient navigation of vessels between different water levels, facilitating trade and commerce across vast distances. The Greeks' mastery of hydraulic engineering and canal construction techniques played a crucial role in the development of maritime infrastructure.

Ancient Suez Canal: The Ancient Suez Canal, opened by Greek engineers under Ptolemy II in the early 3rd century BC, connected the Red Sea to the Mediterranean, providing a vital trade route between the East and West. This monumental feat of engineering enabled the efficient transportation of goods and fostered cultural exchange between civilizations. The construction and maintenance of the canal demonstrated the Greeks' expertise in large-scale infrastructure projects and their role in shaping global trade routes.

Lighthouse: While the exact origins of lighthouses are debated, Greeks made significant contributions to their development, with structures like the Lighthouse of Alexandria and the one established by Themistocles at Piraeus in the 5th century BC. These beacon towers provided essential navigation aids for mariners, guiding ships safely into harbors and marking dangerous coastlines. The Greeks' mastery of architectural and maritime engineering ensured safe passage for seafarers and contributed to the growth of maritime trade and exploration.

Water wheel: Philo of Byzantium described the water wheel in the 3rd century BC, marking a significant advancement in mechanical engineering and hydropower technology. Water wheels harness the energy of flowing water to perform mechanical work, such as grinding grain or pumping water, and played a crucial role in powering mills and other industrial processes. The Greeks' development of the water wheel revolutionized agriculture, manufacturing, and resource management, paving the way for future innovations in renewable energy.

Alarm clock: Ctesibius, a Hellenistic engineer, devised the alarm clock in the 3rd century BC, incorporating it into his clepsydras to indicate time. This early timekeeping device featured elaborate alarm systems, including dropping pebbles on a gong or blowing trumpets, to awaken users at pre-set times. The invention of the alarm clock enhanced productivity and time management, contributing to the Greeks' advancements in horology and mechanical engineering.

Odometer: Invented in the 3rd century BC, the odometer revolutionized transportation and road construction by accurately measuring distances traveled by vehicles. Whether attributed to Archimedes or Heron of Alexandria, the odometer provided a vital tool for trade, military logistics, and urban planning. Its widespread adoption facilitated the development of road networks and contributed to the expansion of commerce and communication across the ancient world.

Chain drive: Philo of Byzantium described the chain drive in the 3rd century BC, powering the repeating crossbow and other mechanical devices. This innovative mechanism transferred rotational motion between axles, enabling complex machinery and automation. The Greeks' mastery of the chain drive laid the foundation for future developments in power transmission and industrial engineering, influencing technologies from clockwork mechanisms to modern-day vehicles.

Cannon: Ctesibius of Alexandria developed a primitive form of the cannon in the 3rd century BC, utilizing compressed air as a propellant. This early artillery weapon demonstrated the Greeks' ingenuity in military technology and their ability to harness natural forces for strategic advantage. The invention of the cannon revolutionized warfare, shaping tactics and fortifications in ancient and medieval times.

Double-action principle: Ctesibius applied the double-action principle in the 3rd century BC to his piston pump, enhancing its efficiency and functionality. This universal mechanical principle, which involves the alternating application of force in two directions, facilitated the development of hydraulic systems and pneumatic devices. The Greeks' understanding of the double-action principle laid the groundwork for advancements in fluid mechanics and engineering, contributing to innovations in irrigation, mining, and manufacturing.

Levers: Archimedes described levers around 260 BC, recognizing their fundamental role in mechanical advantage and force amplification. While levers had been used in prehistoric times, the Greeks' systematic study and application of levers advanced their use in various technologies, from construction to warfare. The Greeks' mastery of leverage principles revolutionized engineering and allowed for the development of sophisticated machines and devices.

Water mill: The Greeks pioneered the use of water power in mills around 250 BC, as evidenced by Philo's writings. Water mills utilized flowing water to turn millstones, grinding grains and performing other tasks essential to ancient economies. The widespread adoption of water mills transformed agriculture, industry, and commerce, driving economic growth and technological innovation across the ancient world.

Three-masted ship (mizzen): Hiero II of Syracuse introduced the three-masted ship, featuring a mizzen mast, around 240 BC. This innovative sail configuration improved stability and maneuverability, enhancing maritime trade and naval warfare capabilities. The Greeks' mastery of ship design and navigation facilitated exploration and colonization, shaping the course of ancient Mediterranean civilizations.

Gimbal: Philo of Byzantium described the gimbal in the 3rd century BC, introducing a revolutionary mechanism for stabilizing objects and maintaining their orientation. This ingenious device, consisting of concentric rings allowing free rotation, found applications in navigation, astronomy, and mechanical engineering. The Greeks' invention of the gimbal enabled precise measurement and control in various fields, contributing to advancements in science and technology.

Dry dock: Invented in Ptolemaic Egypt around 200 BC, the dry dock provided a revolutionary solution for repairing and maintaining ships. Athenaeus of Naucratis documented its use under Ptolemy IV Philopator, highlighting its importance in maritime infrastructure. Dry docks facilitated shipbuilding and naval operations, supporting trade networks and military expeditions throughout the ancient world.

Fore-and-aft rig (spritsail): Spritsails, the earliest fore-and-aft rigs, appeared in the Aegean Sea in the 2nd century BC. These innovative sail configurations improved maneuverability and sailing efficiency, allowing ships to navigate closer to the wind. The Greeks' development of fore-and-aft rigs revolutionized maritime transportation, influencing ship design and navigation techniques for centuries to come.

Air and water pumps: Ctesibius and other Greek engineers in Alexandria developed air and water pumps in the 2nd century BC, serving various practical purposes. These devices, including water organs and Heron's fountain, utilized pneumatic and hydraulic principles to create pressurized air and water systems. The Greeks' mastery of pump technology enabled advancements in irrigation, plumbing, and mechanical engineering, supporting urban infrastructure and technological innovation.

Sakia gear: The Sakia gear, fully developed in 2nd-century BC Hellenistic Egypt, revolutionized agricultural irrigation systems. This mechanical device, depicted in ancient pictorial evidence, enabled the efficient transfer of water from rivers or wells to fields, increasing agricultural productivity. The Greeks' invention of the Sakia gear transformed farming practices, supporting population growth and urbanization in ancient civilizations.

Surveying tools: Greek records dating to the 2nd century BC mention various surveying tools used in the construction of aqueducts and other engineering projects. These precision instruments, including the groma and dioptra, facilitated accurate measurements of land and topography, essential for urban planning and infrastructure development. The Greeks' advancements in surveying technology laid the foundation for civil engineering and architectural innovation, shaping the built environment of ancient cities.

Analog computers: The Antikythera mechanism, discovered in the early 20th century, represents an ancient Greek analog computer designed for astronomical calculations. This remarkable device, dated to around 150 BC, utilized intricate gear systems to predict celestial events and lunar phases. The Greeks' development of analog computers, including the astrolabe, revolutionized scientific inquiry and navigation, providing valuable tools for understanding the cosmos and mapping the heavens.

Fire hose: Heron of Alexandria invented the fire hose in the 1st century BC, based on Ctesibius' piston pump design. This innovative firefighting device utilized pressurized water to extinguish flames, improving fire safety and disaster response in ancient cities. The Greeks' development of the fire hose marked a significant advancement in emergency management and urban infrastructure, enhancing public safety and resilience to fire hazards.

Vending machine: Heron of Alexandria described the first vending machine in the 1st century BC, featuring a coin-operated mechanism for dispensing holy water. This early example of automated vending showcased the Greeks' ingenuity in engineering and mechanical design, providing convenient access to goods and services in public spaces. The invention of the vending machine laid the groundwork for future advancements in automation and retail technology, influencing modern vending industry practices.

Wind vane: The Tower of the Winds in Athens, dating to around 50 BC, featured a bronze wind vane in the form of a Triton rotating to the wind. This sophisticated weather instrument, adorned with wind deities, provided valuable meteorological data for sailors and city dwellers. The Greeks' development of the wind vane demonstrated their understanding of atmospheric dynamics and their ability to apply scientific principles to practical engineering solutions, supporting maritime navigation and urban planning efforts.

Clock tower: The Tower of the Winds in Athens, built around 50 BC, served as a clock tower equipped with sundials and a water clock. This ancient timekeeping device provided accurate time measurements for city residents and travelers, facilitating daily activities and public events. The Greeks' construction of clock towers represented a significant advancement in horology and urban infrastructure, demonstrating their commitment to precision timekeeping and civic organization.

Automatic doors: Heron of Alexandria proposed schematics for automatic doors in the 1st century AD, utilizing steam power to operate temple entrances. These early examples of automated doors showcased the Greeks' innovative approach to architectural design and mechanical engineering. The invention of automatic doors enhanced convenience and accessibility in public spaces, laying the groundwork for future advancements in automation and building technologies.