New findings rewrite the story of the mysterious Hatshepsut – A ceremonial “de-spiritualization” sheds new light on her legacy.

For centuries, the disappearance of Pharaoh Hatshepsut from Egypt’s official history remained a puzzle. A groundbreaking new study now challenges the long-standing belief that her memory was erased out of hatred and political vengeance.

Hatshepsut—whose name means “Foremost of Noble Ladies”—was one of only three women to rule as Pharaoh over the course of 3,000 years of ancient Egyptian history, and the first to wield full power. Though renowned, she has long remained enigmatic, largely because of the apparent effort to eliminate her from the historical record.

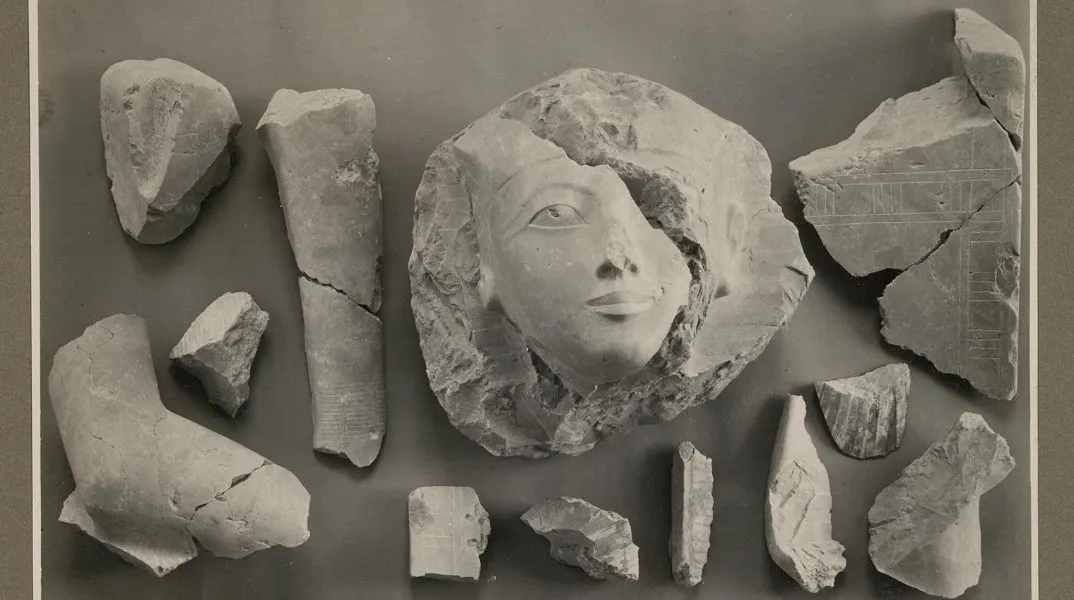

But according to new research, the statues of Queen Hatshepsut were not violently destroyed as part of a campaign to obliterate her memory. Instead, they were likely ritually “deactivated.” This reinterpretation stems from a detailed study of the statues unearthed in the 1920s at Deir el-Bahari in Luxor, about 500 kilometers south of Cairo.

The lead researcher, June Yee Wong from the University of Toronto, published her findings in the journal Antiquity. She argues that the condition of these statues—long believed to be the result of deliberate, hostile destruction by her successor and nephew, Thutmose III—actually points to something else.

“Because the statues were found in highly fragmented condition, it was assumed they had been violently smashed by Thutmose III, perhaps out of resentment toward Hatshepsut,” Wong explains.

Hatshepsut initially ruled as regent on behalf of the young Thutmose III, but eventually declared herself Pharaoh. After her death, her images and name were systematically removed from temples and monuments, leading many scholars to conclude that Thutmose III sought to rewrite history. Others assumed his actions were driven by spite.

A Different Kind of Destruction

Wong examined excavation records and unpublished archival materials from the 1920s to determine the exact locations and conditions in which the statue fragments were discovered. Her analysis revealed that much of the damage occurred long after Thutmose’s reign, likely during periods when the statues were broken up and reused as construction material—adding complexity to the traditional narrative.

When Wong excluded the later damage, a new picture emerged. The statues appeared to have been systematically broken at specific weak points—such as the neck, waist, and knees—consistent with an ancient Egyptian ritual known as “statue deactivation.”

“When you strip away the later destruction, what remains is limited and deliberate. This wasn't the work of a vengeful attack but a calculated, ritual act, meant to deactivate the power of the statues,” Wong says. “It’s quite astonishing—it shows the treatment of Hatshepsut’s images was more ceremonial than hostile.”

A Ritual of Power and Transition

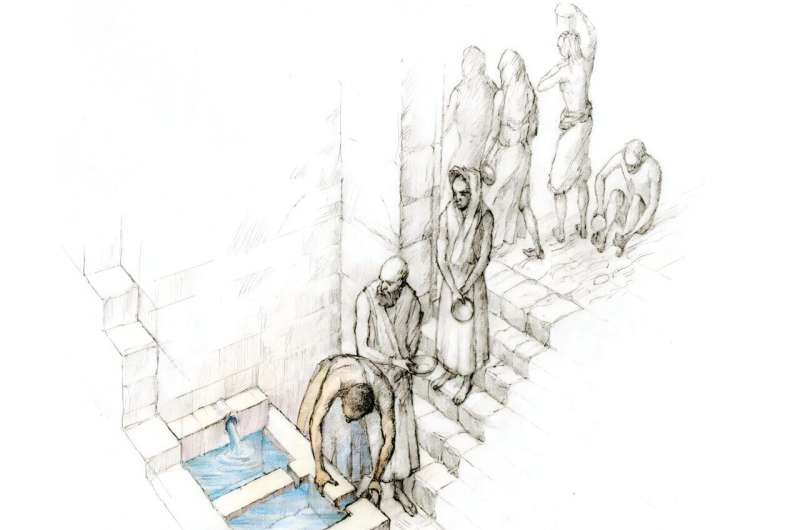

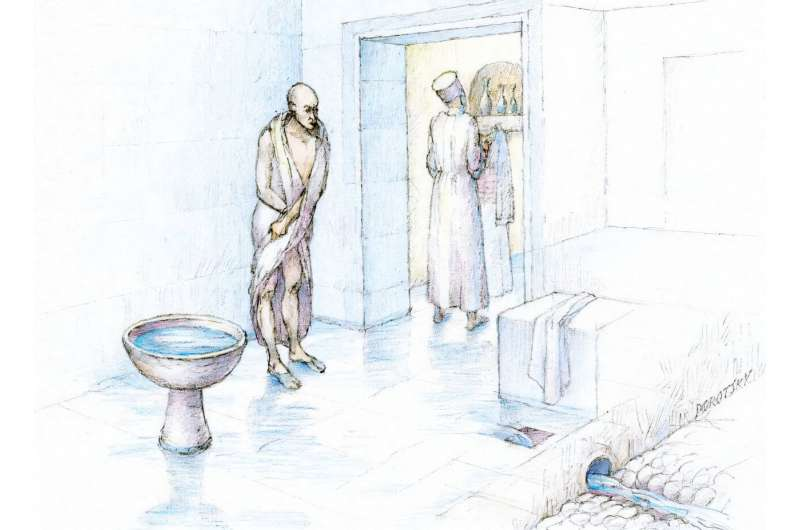

In ancient Egypt, royal statues were seen as vessels of divine presence. Rituals such as the “Opening of the Mouth” were performed to “animate” them, allowing them to act as intermediaries between the gods and the people. But when a statue needed to be removed—say, to make space in a temple—it had to be ritually “de-spiritualized” by breaking key structural points.

This practice neutralized the statue’s power without dishonoring the person it represented. Hundreds of such statues have been found buried at Karnak Temple in Luxor, many similarly “deactivated,” regardless of whether the rulers had been vilified in death.

Though Hatshepsut was clearly subjected to a posthumous “cancelation,” Wong’s findings suggest the process was far more nuanced than once believed.

“The research felt a bit like solving an ancient detective mystery—it was incredibly rewarding to uncover something so tangible,” she says. “People often assume Egyptology is only about discovering tombs and mummies—which is, of course, fascinating—but sometimes the greatest insights come from reinterpreting what’s already been found.”

This new perspective challenges the idea of vengeful erasure and instead opens up a more complex understanding of memory, power, and ritual in ancient Egypt.New findings rewrite the story of the mysterious Hatshepsut – A ceremonial “de-spiritualization” sheds new light on her legacy.

For centuries, the disappearance of Pharaoh Hatshepsut from Egypt’s official history remained a puzzle. A groundbreaking new study now challenges the long-standing belief that her memory was erased out of hatred and political vengeance.

Hatshepsut—whose name means “Foremost of Noble Ladies”—was one of only three women to rule as Pharaoh over the course of 3,000 years of ancient Egyptian history, and the first to wield full power. Though renowned, she has long remained enigmatic, largely because of the apparent effort to eliminate her from the historical record.

But according to new research, the statues of Queen Hatshepsut were not violently destroyed as part of a campaign to obliterate her memory. Instead, they were likely ritually “deactivated.” This reinterpretation stems from a detailed study of the statues unearthed in the 1920s at Deir el-Bahari in Luxor, about 500 kilometers south of Cairo.

The lead researcher, June Yee Wong from the University of Toronto, published her findings in the journal Antiquity. She argues that the condition of these statues—long believed to be the result of deliberate, hostile destruction by her successor and nephew, Thutmose III—actually points to something else.

“Because the statues were found in highly fragmented condition, it was assumed they had been violently smashed by Thutmose III, perhaps out of resentment toward Hatshepsut,” Wong explains.

Hatshepsut initially ruled as regent on behalf of the young Thutmose III, but eventually declared herself Pharaoh. After her death, her images and name were systematically removed from temples and monuments, leading many scholars to conclude that Thutmose III sought to rewrite history. Others assumed his actions were driven by spite.

A Different Kind of Destruction

Wong examined excavation records and unpublished archival materials from the 1920s to determine the exact locations and conditions in which the statue fragments were discovered. Her analysis revealed that much of the damage occurred long after Thutmose’s reign, likely during periods when the statues were broken up and reused as construction material—adding complexity to the traditional narrative.

When Wong excluded the later damage, a new picture emerged. The statues appeared to have been systematically broken at specific weak points—such as the neck, waist, and knees—consistent with an ancient Egyptian ritual known as “statue deactivation.”

“When you strip away the later destruction, what remains is limited and deliberate. This wasn't the work of a vengeful attack but a calculated, ritual act, meant to deactivate the power of the statues,” Wong says. “It’s quite astonishing—it shows the treatment of Hatshepsut’s images was more ceremonial than hostile.”

A Ritual of Power and Transition

In ancient Egypt, royal statues were seen as vessels of divine presence. Rituals such as the “Opening of the Mouth” were performed to “animate” them, allowing them to act as intermediaries between the gods and the people. But when a statue needed to be removed—say, to make space in a temple—it had to be ritually “de-spiritualized” by breaking key structural points.

This practice neutralized the statue’s power without dishonoring the person it represented. Hundreds of such statues have been found buried at Karnak Temple in Luxor, many similarly “deactivated,” regardless of whether the rulers had been vilified in death.

Though Hatshepsut was clearly subjected to a posthumous “cancelation,” Wong’s findings suggest the process was far more nuanced than once believed.

“The research felt a bit like solving an ancient detective mystery—it was incredibly rewarding to uncover something so tangible,” she says. “People often assume Egyptology is only about discovering tombs and mummies—which is, of course, fascinating—but sometimes the greatest insights come from reinterpreting what’s already been found.”

This new perspective challenges the idea of vengeful erasure and instead opens up a more complex understanding of memory, power, and ritual in ancient Egypt.