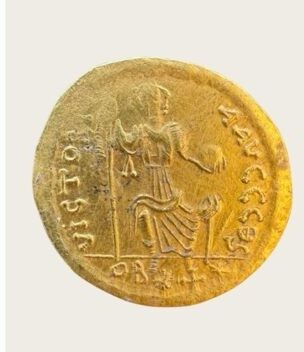

A rare gold coin from the Byzantine Empire, dating to the reign of Emperor Justin II (565–578 CE), was recently unearthed at a fortress site—offering valuable insight into the economic history of Byzantium and the strategic significance of the location.

A Treasure from the Early Byzantine Period

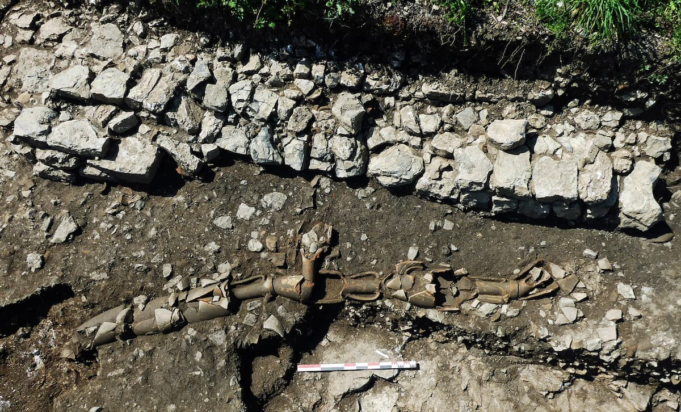

The coin was found at the Tuida Fortress, a site of major strategic importance during the early Byzantine period. Located in the northeastern part of Sliven, Bulgaria, the discovery was announced by the Regional Historical Museum of Sliven.

This find marks the fourth gold coin discovered at Tuida and is especially significant due to its rarity and historical context.

The Emperor Behind the Coin

Emperor Justin II was the nephew and successor of the famous Emperor Justinian I, continuing his uncle’s legacy of ambitious construction and territorial expansion. However, Justin II’s reign was also marked by mounting pressure from the Sassanid Empire in the east and the Lombards in the west.

His rule is historically notable not just for political and military developments, but also for reports of mental instability in his later years—leading his wife, Empress Sophia, and general Tiberius to take control of imperial affairs.

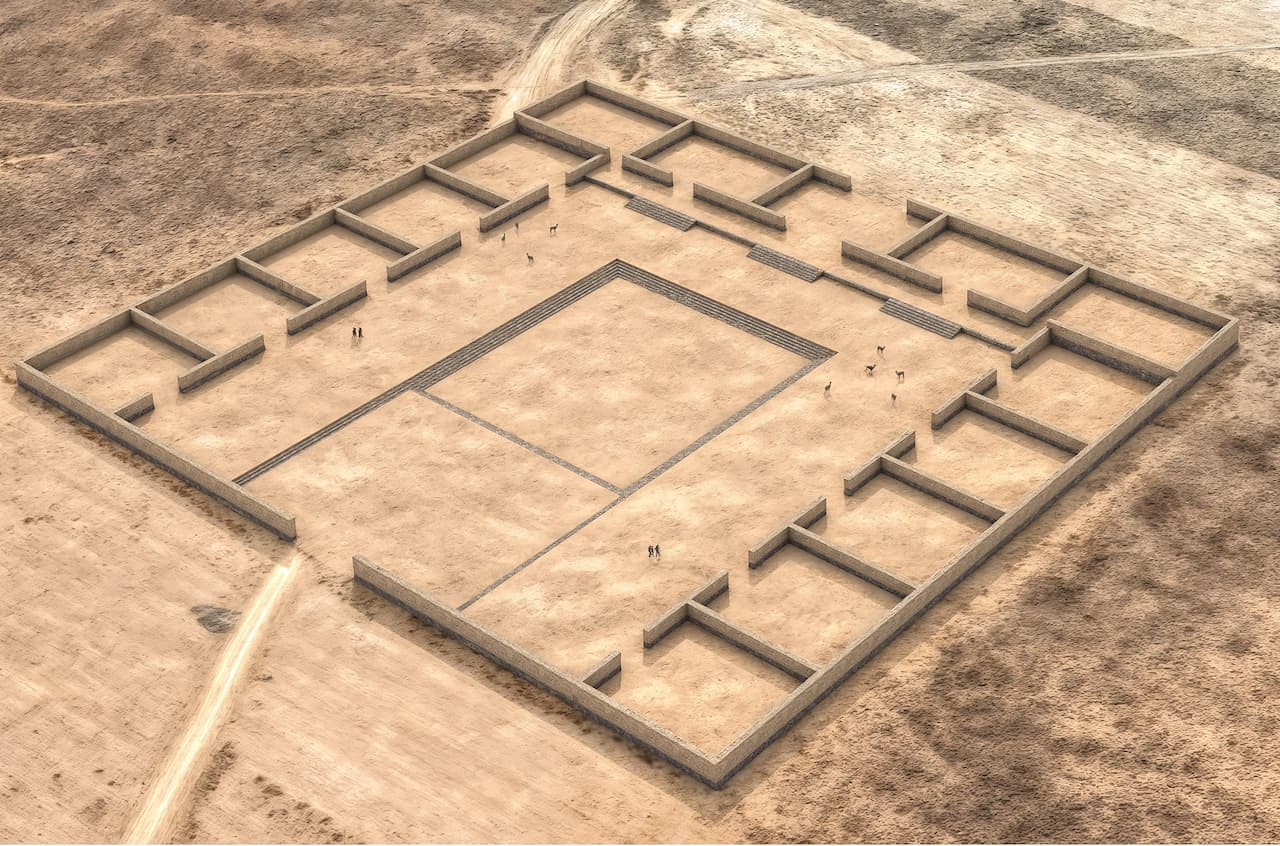

The Fortress of Tuida: A Sentinel Through the Ages

Perched atop Hisarlaka Hill, Tuida Fortress was part of the Stara Planina (Balkan Mountains) defense network. Initially constructed at the end of the Roman period, it was rebuilt during the early Byzantine era. It served as a key military and administrative hub and played a crucial role in the defense of the region throughout Roman, Byzantine, and medieval Bulgarian history—guarding trade routes and deterring invasions.

Details of the Discovery

Initially believed to date to Justinian I’s reign, the coin was confirmed—after cleaning and analysis—to belong to Justinian II’s rule. On its obverse (front side), the coin features a bust of the emperor holding an orb topped with the Roman goddess Victory (Nike).

The Latin inscription reads:

D N IVSTINVS P P AVG, which translates to:

D N = Dominus Noster = Our Lord

IVSTINVS = Justin (name)

P P = Perpetuus (or Perpetuus Pontifex) = Eternal

AVG = Augustus = The Revered One

Together: “Our Lord Justin, Eternal Augustus”—a traditional imperial title reflecting divine authority and sovereignty.

The reverse side bears the inscription: VICTORIA AVGGG ΘS, commonly seen on Roman and Byzantine coins. It breaks down as:

VICTORIA = Victory

AVGGG = Plural of Augustus, suggesting three emperors (possibly representing a triarchy or shared rule)

ΘS = Abbreviation from the Greek “Theos” = God or Divine

This side also features Emperor Justin holding an orb with Nike, gazing forward. Experts believe the coin was likely minted in Theopolis—the historical name for Antioch, one of the Byzantine Empire’s most significant cities.

Located in modern-day southern Turkey, near the Syrian border, Antioch was a major administrative, commercial, and religious hub during both the Roman and Byzantine eras. The “ΘS” mint mark supports the theory that the coin was struck at the Antioch mint, further enhancing the find’s historical and geographical importance.

Why This Find Matters

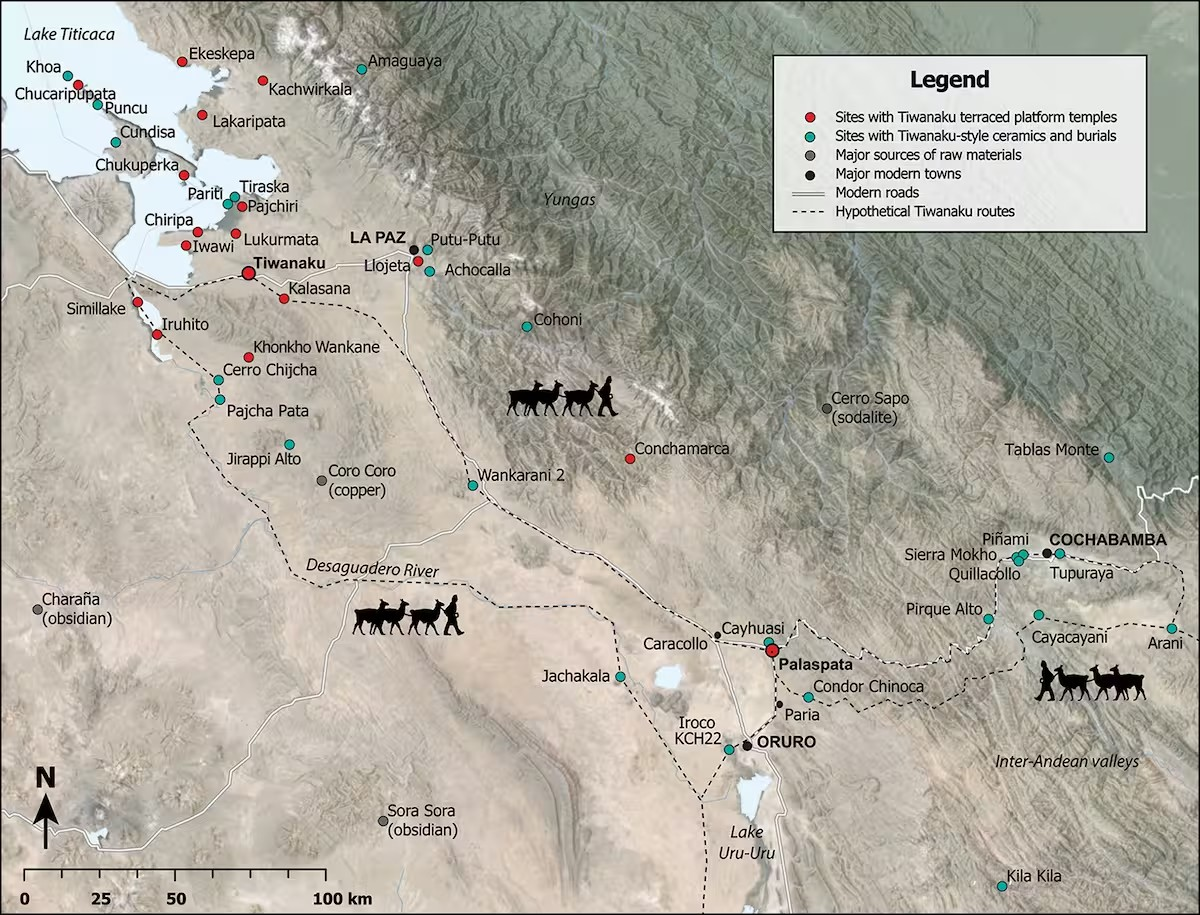

To date, archaeologists have uncovered 23 coins at Tuida during this season alone, ranging from the 2nd–3rd centuries CE to the 12th–13th centuries. These discoveries provide a wealth of information about continuous habitation and regional importance during centuries of political upheaval.

The discovery of this rare solidus of Justin II adds significantly to the numismatic and economic history of Byzantium. It also highlights Tuida Fortress’s role as a vital link in the empire’s defensive and administrative network during the early Byzantine period.

For historians and scholars alike, this gold artifact opens new windows into the rich cultural heritage of the Byzantine Empire in southeastern Europe, while reinforcing the legacy of Sliven—one of Bulgaria’s oldest continually inhabited regions.