A recent study published in Journal of Anthropologie (July 2025) has dramatically reshaped our understanding of the encounters between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. The research focuses on the skull of a five-year-old child, known as Skhul I, discovered almost a century ago in the Skhul Cave at Mount Carmel, Israel. Using modern CT imaging, scientists now argue that this fragment represents the earliest known human fossil that so strongly combines features of both species—externally resembling Homo sapiens, yet internally carrying unmistakable Neanderthal traits.

This revelation not only shifts the timeline of interbreeding between our species and Neanderthals but also forces us to reconsider the evolutionary story itself. It shows that our lineage has always been hybrid at its core, shaped by encounters, exchanges, and blending rather than by a neat succession of “pure” populations.

The Discovery of Skhul I: An Old Fossil Revisited

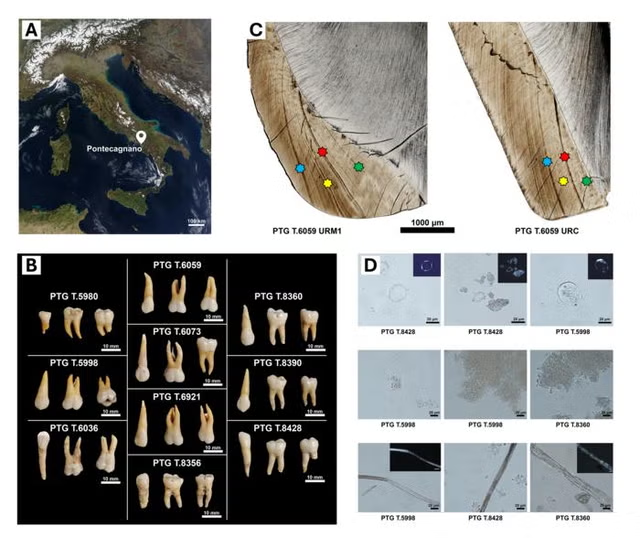

The remains of Skhul I were first unearthed nearly 90 years ago during excavations led by British archaeologists Dorothy Garrod and Theodore McCown. At the time, the child’s skeleton was classified as early Homo sapiens due to its rounded skull vault and other “modern” features. However, paleoanthropologists always noted a curious mix: some elements seemed less typical, hinting at Neanderthal affinities.

For decades, the specimen was treated as a borderline case—perhaps transitional, perhaps simply variation within early Homo sapiens. What it lacked was the precision of modern imaging technology. With the application of high-resolution CT scans, researchers were able to analyze the internal structures of the skull and jaw with unprecedented clarity. And what they found was nothing short of groundbreaking: beneath a Homo sapiens-like exterior lay a framework strikingly similar to that of Neanderthals.

The skull of Skhul I child showing cranial curvature typical of Homo sapiens. Credit: Tel Aviv University

A Hybrid Signature in Flesh and Bone

The new study highlights several features that point to this hybrid identity.

Cranial Vault: The rounded, globular shape is consistent with Homo sapiens, reflecting a brain form we associate with our species.

Vascular Impressions: The pattern of blood vessel channels inside the skull shows Neanderthal-like organization, revealing a deeper kinship with that lineage.

Mandible and Ear Structure: The lower jaw and the internal ear morphology strongly echo Neanderthal anatomy, diverging from the more gracile Homo sapiens form.

Taken together, these findings suggest Skhul I was not simply an early Homo sapiens child but the product of a much earlier intermingling between populations—long before the commonly accepted timeline.

Shattering the Chronology: Interbreeding Twice as Old as We Thought

Until recently, the dominant genetic narrative placed interbreeding between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals between 60,000 and 40,000 years ago, during the great migrations out of Africa. Ancient DNA studies showed that non-African humans carry about 2–4% Neanderthal DNA, a legacy of those encounters.

Skhul I, however, is dated to roughly 140,000 years ago. This pushes back the evidence of mixing by nearly 80,000 years. In other words, the first genetic exchanges between sapiens and Neanderthals occurred not in Europe or Central Asia during the last Ice Age, but much earlier, likely in the Levant—one of the most important crossroads of human evolution.

This child is thus the earliest tangible witness to a story of contact, union, and shared life between two species.

Body and Brain: A Mosaic of Evolution

Credit: Tel Aviv University

The most fascinating aspect of Skhul I is not just that it mixes traits but that it does so in both body and brain. Hybridization here is not superficial. It extends to the very architecture of the cranium—the space that houses cognition, perception, and social behavior.

This mosaic anatomy suggests that human evolution was never a simple sequence of one species replacing another. Instead, it was messy and interactive. Populations met, exchanged genes, shared ideas and technologies, and sometimes raised children who embodied both lineages. Skhul I represents one such child—living proof that identity in prehistory was blurred, fluid, and relational.

Cultural and Social Implications

The existence of Skhul I raises important questions about the nature of Neanderthal-sapiens interaction. Were these isolated encounters, or was there sustained coexistence? Archaeological evidence from the Mount Carmel region shows overlapping tool traditions and burial practices. This suggests that the two populations may have shared not only territory but aspects of culture.

If Homo sapiens and Neanderthals were raising children together 140,000 years ago, we must imagine families that combined traditions, perhaps languages, and worldviews. Such unions could have been rare and exceptional, or they could have been part of a long history of social entanglement. Either way, Skhul I is a window into the first “mixed” households of humanity.

Rethinking the Human Story

For decades, evolutionary narratives were dominated by a model of replacement: modern humans emerged in Africa and eventually outcompeted or exterminated Neanderthals. While genetic evidence has already softened this story by showing interbreeding, the discovery of Skhul I makes it impossible to ignore how deep and ancient this blending truly was.

The implication is that humanity is not a “pure” lineage at all but a palimpsest of interactions. We are hybrids by origin, carrying echoes of more than one hominin species in our DNA, bodies, and perhaps even in aspects of cognition and behavior.

This is not a weakness but a strength. Diversity and mixture gave us resilience, adaptability, and creativity. The blurred boundaries between sapiens and Neanderthals may have enriched both species, even if one lineage eventually disappeared.

Why This Child Matters Today

Skhul I is not merely an archaeological curiosity; it is a symbol. It reminds us that our history is a story of meeting, blending, and co-creation. At a time when human societies often obsess over purity, origins, and boundaries, this fossil offers a very different lesson: the human condition is hybrid. We are who we are because of encounters that crossed lines, defied categories, and forged unexpected kinships.

The child at Mount Carmel was buried with care, suggesting that even in deep prehistory, people understood the value of life, no matter how unusual its origins. That act of burial links us directly to them, across 140,000 years, in a chain of memory and belonging.

Conclusion: A Mirror of Our Shared Nature

The oldest known human fragment that combines both species so intensely in body and brain is more than a scientific discovery—it is a mirror. It reflects the truth that identity has always been complex, layered, and shared.

Skhul I challenges us to imagine prehistory not as a battlefield of species but as a landscape of encounters, families, and exchanges. It shows that evolution’s greatest tool was not isolation but connection. And in that light, our deepest legacy is not competition, but the capacity to meet the other and become something new together.

The child of Skhul, resting for 140,000 years in the earth of Mount Carmel, is now speaking again. What it tells us is simple but profound: humanity has always been a conversation, not a monologue.