A recent archaeological discovery of more than 600 pieces of red ochre at a 6,500-year-old ritual site near Carlisle, in northwestern England, appears to confirm one of the earliest Greek accounts of the inhabitants of Britain. According to Pytheas of Massalia, a 4th-century BCE Greek explorer, the island’s inhabitants were called the Prettanoi, or “the painted people,” because they traditionally painted their bodies. The term Prettanike used by Pytheas likely derives from the Celtic word Pretani, meaning “the painted” or “the tattooed.” This tradition was later mentioned by Julius Caesar in the 1st century BCE, who noted that the Britons habitually painted their bodies.

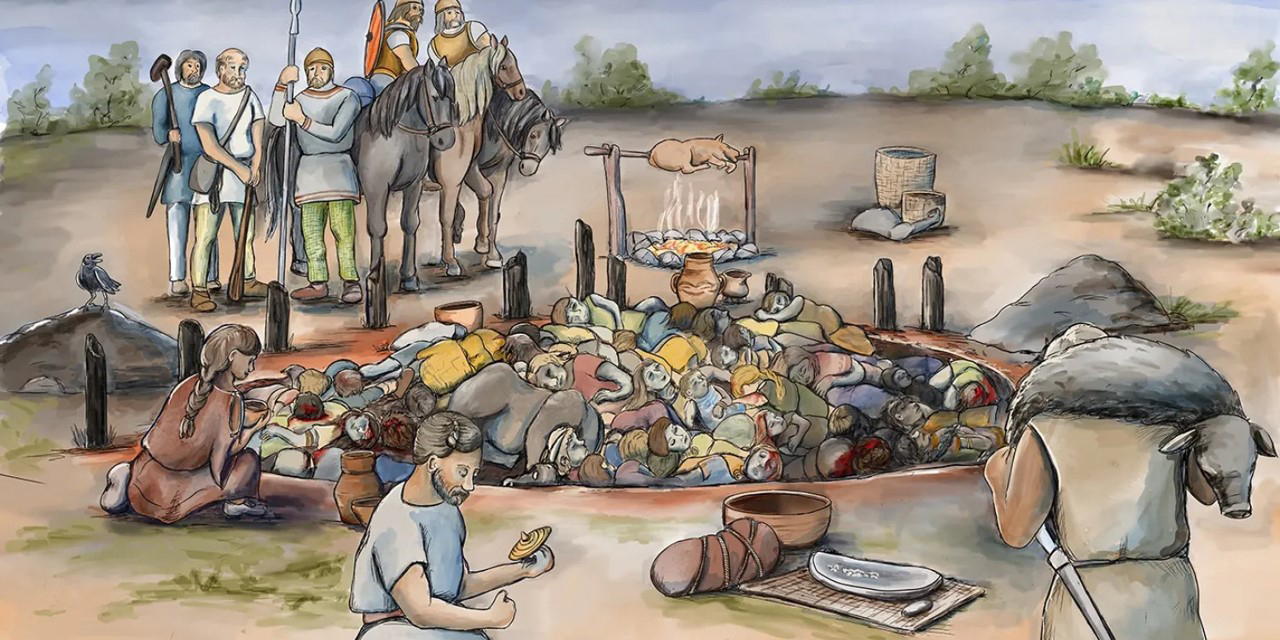

The Carlisle discovery, the largest find of ochre in Britain to date, strengthens both the linguistic and historical evidence. Archaeologists suggest that the site was used for large gatherings or festivals, likely coinciding with the spring salmon fishing season, and that the ochre was used in body-painting rituals. Alongside the ochre fragments, they found stones for grinding it into powder, as well as hundreds of thousands of flint fossils, indicating large-scale activity at the site.

Pytheas, who came from Massalia (modern Marseille), was the first Mediterranean explorer to reach and study Britain. He is also believed to have traveled as far as Iceland and the Arctic Circle, where he recorded the phenomenon of the midnight sun for the first time. His written work, On the Ocean, has not survived, but his observations are preserved in the writings of later geographers such as Strabo, Pliny the Elder, and Diodorus Siculus.

According to these sources, around 330 BCE, Pytheas crossed the English Channel and first landed in Cornwall, where he described the tin trade. From there, he traveled north along the coasts of England, Wales, and Scotland, observing the local Celtic-speaking populations, whom he called the Prettanoi.

Although the Carlisle ochre dates back thousands of years before Pytheas’s journey, archaeologists note that red ochre continued to be used by prehistoric Britons up to the Iron Age. This suggests that the body-painting tradition may have been preserved over millennia, potentially connecting directly to the description left by the Greek explorer of the people of Prettanike.