The earliest known evidence for the use of arrow poison was long believed to come from Egypt, dating back about 4,000 years. This took the form of a black, toxic residue found on bone arrowheads in a tomb at the Naga ed Der archaeological site.

New discoveries from southern Africa are now challenging that view.

Recent research has identified poison residues on stone arrow tips from South Africa dating to around 60,000 years ago, making this the oldest direct evidence of poisoned arrows used for hunting.

These findings add to existing knowledge about the technical skills of early African bowhunters. Such expertise may have played a role in the long-term success of our species in the region and later supported the spread of Homo sapiens beyond Africa.

The evidence comes from Umhlatuzana Rock Shelter in South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal province. The site was partially excavated in the 1980s to protect archaeological material at risk from construction of the N3 highway linking Durban and Pietermaritzburg.

Two of the authors (Marlize Lombard and Anders Högberg) at Umhlatuzana rock shelter, where the poisoned arrow tips were excavated.

Umhlatuzana is recognised as a significant Stone Age site where hunter-gatherers were living at least 70,000 years ago. It is also one of the few locations in southern Africa that shows evidence of continued human occupation until just a few thousand years ago.

In southern Africa, there is a long tradition of hunting with poisoned arrows. For instance, South African and Swedish archaeologists have identified residues on arrow tips dating from a few hundred to about 1,000 years ago, revealing the use of different poison recipes.

More recently, three bone arrowheads kept inside a poison-filled bone container were reported from Kruger Cave in South Africa and dated to nearly 7,000 years ago. This discovery pushed back direct molecular evidence for the use of arrow poison to around 3,000 years earlier than the Egyptian examples.

Earlier traces of poison had been identified on a stick and in a lump of beeswax from Border Cave in KwaZulu-Natal, dating between 35,000 and 25,000 years ago. However, these were considered indirect indications of early hunting poisons.

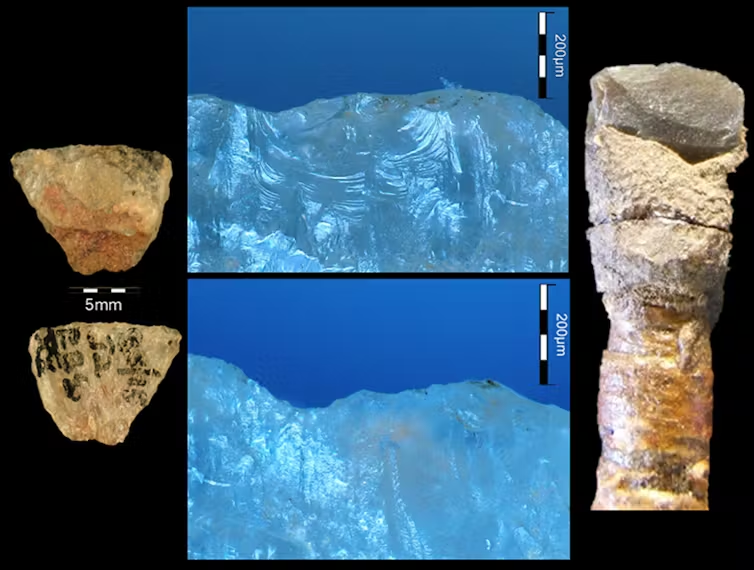

As a researcher in cognitive and Stone Age archaeology, I examined artefacts from Umhlatuzana almost 20 years ago and identified use-wear and adhesive residues on some quartz backed microliths—small, shaped stone tools—dating to around 60,000 years ago. This suggested they were likely used as arrow tips.

More recently, Sven Isaksson of the archaeology laboratory at Stockholm University has identified molecular traces of toxic plant alkaloids—chemical compounds known to be used as arrow poisons—on several of these artefacts.

Left: Front and back of a 60,000-year-old poisoned arrow tip from Umhlatuzana. Middle: Two micrographs of the sharp, top edge that shows impact scars and the direction in which the arrow tip was fixed in the shaft. Right: A 2,000-year-old arrow head with stone tip fixed in the same way as the arrow tip from Umhlatuzana.

Poison from indigenous plants

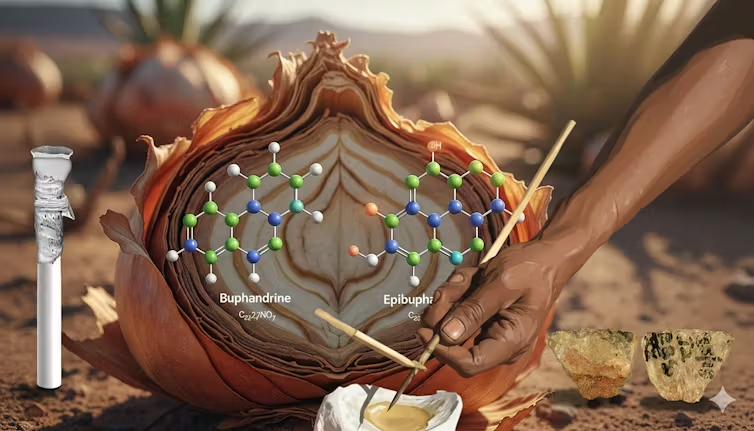

The new study identified the toxic alkaloids buphandrine and epibuphanisine on five of the ten arrow tips analysed from Umhlatuzana. These same compounds were also detected on bone arrowheads collected by Swedish travellers in southern Africa about 250 years ago, indicating that the same type of arrow poison was used in the region for thousands of years.

Both alkaloids occur in several southern African plants belonging to the Amaryllidaceae family, which grow from bulbs. However, the plant most clearly documented as a source of arrow poison is Boophone disticha, commonly known as gifbol (poison bulb). Its bulb produces a highly toxic sap.

The presence of these specific alkaloids on half of the quartz arrow tips examined is unlikely to be accidental. Ancient hunter-gatherers would have been well aware of the poisonous properties of gifbol. Evidence from the region shows that by around 77,000 years ago, people already understood how to use certain aromatic plants for their insecticidal and larvicidal effects in bedding. This suggests they would also have known to handle gifbol carefully and avoid keeping it in living areas.

Modern contamination can be ruled out, as substances containing buphandrine and epibuphanisine are not used in commercial products or in archaeological conservation.

Gifbol bulbs are remarkably resilient, capable of surviving for a century or more despite droughts and frequent fires. The plant is native to South Africa and thrives in grassland, savanna and Karoo environments. It is widespread across southern, eastern and northern South Africa and grows within a day’s walk of Umhlatuzana Rock Shelter today. For these reasons, it is very likely that the plant was also available to the site’s inhabitants tens of thousands of years ago.

The toxic compounds in the bulb are chemically stable. They break down very slowly, even in wet conditions, and bind well to mineral surfaces such as stone arrow tips. This stability helps explain how traces of the poison were able to survive on the artefacts for around 60,000 years.

Illustration of gifbol being prepared for use in hunting.

Implications of the world’s oldest known poisoned arrow tips

The quartz arrow tips coated with gifbol poison now constitute the earliest direct evidence of poisoned arrow use, not only in southern Africa but anywhere in the world, dating back 60,000 years.

This discovery shows that early bowhunters had sophisticated knowledge systems that allowed them to recognise poisonous plants, extract their toxic substances, and apply them effectively to weapons. They also needed an understanding of animal behaviour and ecology, knowing that poison would act gradually and weaken prey over time, making it possible to track and eventually capture it through persistence hunting.

Using a weapon whose effects were delayed and not immediately visible points to complex cognitive abilities. It required self-control, as hunters had to wait for the poison to take effect, as well as advanced planning, abstract thinking, and an understanding of cause and effect. Because poison works chemically rather than through direct physical force, its use reflects a high level of conceptual reasoning.

Beyond establishing the earliest known example of poisoned arrow hunting, these findings deepen our understanding of human adaptation, technological and behavioural sophistication, and the development of modern human behaviour in southern Africa.