A significant archaeological find in County Wicklow could change understanding of Ireland’s early urban development. Excavations at the Brusselstown Ring—a large hilltop enclosure in the Baltinglass Hillfort Cluster—have uncovered a massive Late Bronze Age settlement that may predate Viking towns by almost 2,000 years.

Published in Antiquity, the research indicates that prehistoric Irish communities may have created large, complex residential centers long before Norse arrivals in the 9th–10th centuries. Project lead Dr. Dirk Brandherm of Queen’s University Belfast notes that the scale and density of Brusselstown Ring are unprecedented for prehistoric Britain or Ireland.

A Settlement of Exceptional Scale

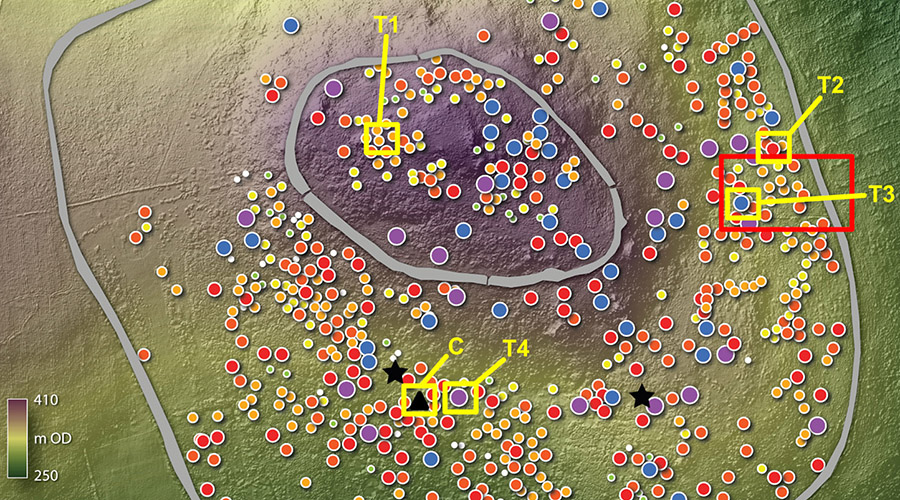

Aerial surveys and detailed mapping revealed over 600 potential roundhouse platforms within the enclosure. Around 100 lie inside an inner rampart, with the remainder spread across the outer enclosure between two defensive walls. The site spans both the main hilltop and adjacent Spinas Hill—a rare layout among European hillforts.

Excavation samples from 2024 date most structures to circa 1200 BC, placing them in the Late Bronze Age, with possible reuse into the Early Iron Age. Researchers describe Brusselstown Ring as the largest known nucleated settlement of its period in the Atlantic Archipelago.

Previously, Bronze Age communities in Ireland were thought to be small and dispersed, made up of isolated farmsteads or tiny hamlets. While discoveries like the Corrstown village (2002) suggested larger settlements existed, the dense cluster at Brusselstown Ring shows a level of organization far beyond a typical village. “The number of domestic structures points to a community resembling a proto-town,” Brandherm explained.

More than 600 suspected house platforms have been identified.

Rethinking the Viking Legacy

For many years, historians credited Viking settlers with founding Ireland’s first towns, including Dublin, Waterford, and Limerick. Brusselstown Ring challenges this view, suggesting that large, centralized settlements may have existed long before Viking arrivals.

If further research confirms its dating, the site could represent one of Europe’s earliest examples of urban-like development outside the classical world. While the term “town” must be applied cautiously in a prehistoric context, the settlement shows traits of concentrated communal living, coordinated construction, and shared infrastructure.

Evidence of Advanced Engineering

Excavations uncovered a stone-lined, flat-floored structure near a trench, likely a cistern fed by an upland spring. If radiocarbon dating confirms it dates to the same period as the roundhouses, it would be Ireland’s first known Bronze Age water storage system of this type, with parallels only in parts of France and Spain.

The engineered water source suggests the settlement was permanent rather than seasonal and points to sophisticated resource management and planning.

Clues to Social Structure

Test digs across four roundhouse platforms revealed a wide range of sizes—from small four-metre buildings to large twelve-metre structures. Archaeologists are exploring whether this reflects social ranking, household status, or functional divisions within the community.

While the evidence remains inconclusive, the variety in architecture indicates that Bronze Age society in the region may have been more socially complex than previously thought.