Introduction

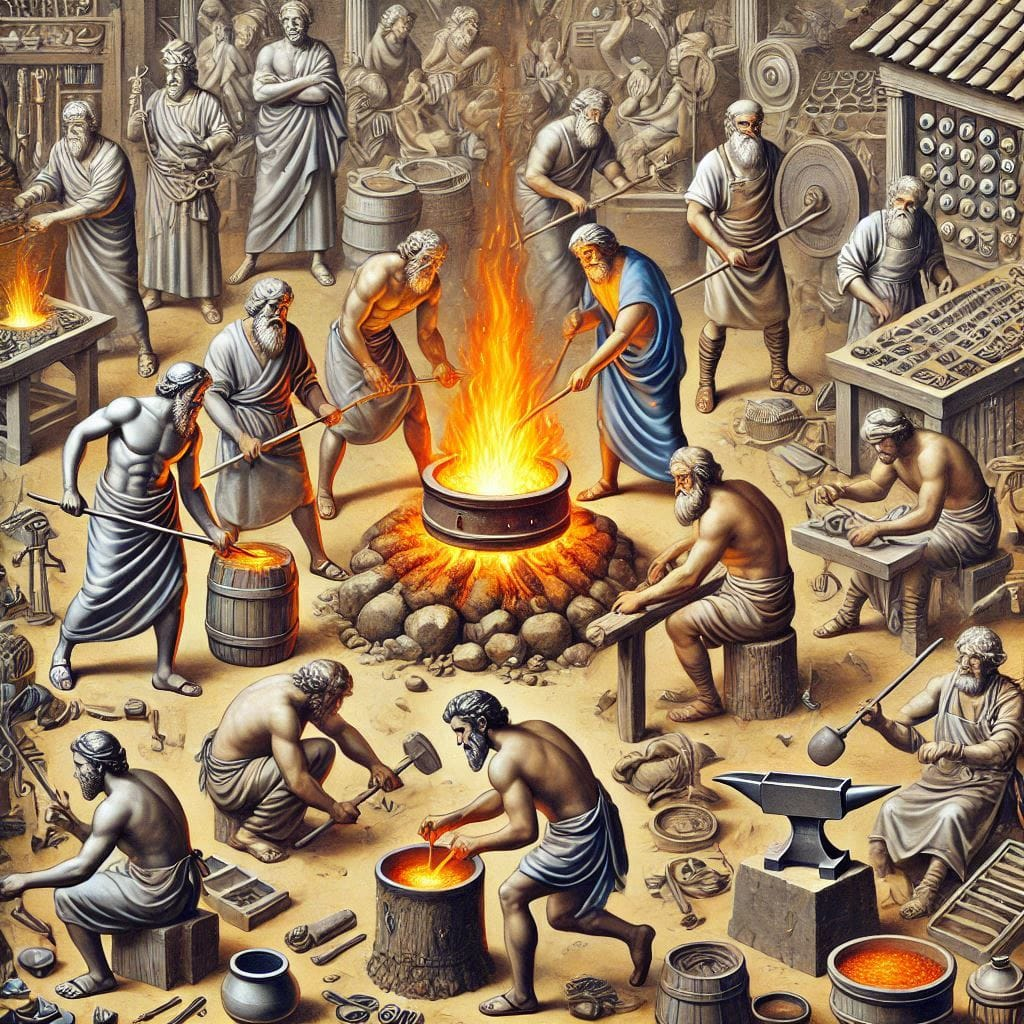

The emergence of metallurgy represents one of the most transformative developments in human history. Long before iron reshaped economies and warfare, the first metalworkers learned to extract copper from stone and later alloy it with tin to create bronze, inaugurating a technological and social revolution that permanently altered the trajectory of human evolution. These early metallurgists were not merely craftsmen; they were innovators whose knowledge of materials, fire, and chemistry reshaped tools, trade networks, social hierarchies, and cultural identities. The mastery of metals marked a decisive shift away from purely stone-based technologies and laid the foundations for complex societies.

This article explores the origins and development of early copper and bronze metallurgy, examining the archaeological evidence for the first metalworkers, their tools and furnaces, the techniques they developed, and the broader cultural consequences of their innovations. Drawing on major archaeological sites, artifacts, and scholarly interpretations, it situates early metallurgy within the wider context of human adaptation and technological change.

Historical Background: From Stone to Metal

The Limits of Stone Technologies

For hundreds of thousands of years, human societies relied almost exclusively on stone, bone, wood, and other organic materials to manufacture tools. Stone tool technologies became increasingly sophisticated during the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods, yet they remained constrained by the physical properties of stone. Stone tools could be sharp and durable, but they were brittle and difficult to reshape once manufactured. As populations grew and economic activities diversified, these limitations became more apparent.

The Neolithic period, characterized by the adoption of agriculture and sedentary settlement, created new demands for tools capable of sustained use in farming, construction, and craft production. Axes, adzes, sickles, and chisels were essential for clearing land and processing crops, but stone versions required frequent replacement. The search for more versatile and durable materials set the stage for experimentation with metals.

Native Metals and Early Experimentation

The earliest encounters with metal likely involved native copper, gold, and silver, which can occur in relatively pure forms in nature. Unlike ores that require complex smelting, native metals can be hammered and shaped when cold. Archaeological evidence suggests that small copper objects were produced as early as the ninth millennium BCE in parts of the Near East and Anatolia. These early items, often beads or small ornaments, were initially valued for their visual appeal rather than functional superiority.

Over time, repeated heating and hammering led to accidental discoveries about metal properties, including annealing, which restores ductility after work hardening. Such observations gradually transformed metals from decorative curiosities into practical materials for tools and weapons.

The Rise of Copper Metallurgy

Smelting: A Revolutionary Discovery

The true breakthrough in metallurgy occurred with the discovery of smelting, the process of extracting metal from ore using heat. Copper ores such as malachite and azurite change color when heated, a property that may have drawn early experimenters to place them in hearths or kilns. When heated to sufficiently high temperatures in a reducing environment, these ores yield metallic copper.

Archaeological evidence for early copper smelting dates to the late seventh and sixth millennia BCE. Sites in Anatolia, the Levant, and the Iranian plateau have yielded slag, crucibles, and copper droplets indicative of deliberate metallurgical activity. Smelting required careful control of temperature and airflow, suggesting a growing understanding of pyrotechnology.

Early Furnaces and Tools

Early copper furnaces were relatively simple structures, often consisting of shallow pits lined with clay or stone. Charcoal served as the primary fuel, capable of producing the high temperatures necessary for smelting. Blowpipes or simple bellows were used to introduce oxygen and intensify combustion.

The tools associated with early copper working included stone hammers, anvils, and molds made from clay or stone. Casting techniques gradually replaced purely hammered production, allowing for more standardized shapes. Flat axes, awls, chisels, and small blades became increasingly common during the Chalcolithic period, also known as the Copper Age.

Major Copper Metallurgy Sites

Several archaeological sites have become central to understanding early copper metallurgy. Çatalhöyük in Anatolia provides evidence of early experimentation with copper artifacts within a Neolithic context. At Timna in the southern Levant, extensive mining and smelting installations reveal organized copper production during the late prehistoric and early historic periods. In southeastern Europe, sites such as Belovode in Serbia have yielded some of the earliest securely dated evidence of copper smelting, dating to the mid-sixth millennium BCE.

These sites demonstrate that copper metallurgy emerged independently or semi-independently in multiple regions, driven by local resources and cultural traditions.

The Invention of Bronze

Alloying and Innovation

The transition from copper to bronze marks a critical turning point in metallurgical history. Bronze, an alloy of copper and tin (or occasionally arsenic), possesses superior hardness, durability, and casting properties compared to pure copper. The deliberate creation of bronze required a conceptual leap: the understanding that combining different materials could produce a substance with new and improved characteristics.

Early bronze objects appear in the late fourth millennium BCE, particularly in Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and the Caucasus. Initially, arsenical bronze, created by smelting copper ores naturally containing arsenic, may have been produced unintentionally. Over time, metallurgists learned to control alloy composition, leading to the widespread adoption of tin bronze.

Tin Sources and Long-Distance Trade

Tin is relatively rare compared to copper, and its uneven geographic distribution had profound implications for early societies. Major tin sources are found in regions such as Central Asia, Anatolia, and later in parts of Europe. The need to obtain tin encouraged the development of long-distance trade networks, linking distant communities through exchange.

Archaeological evidence for tin trade includes chemical analyses of bronze artifacts that trace tin back to specific geological sources. These findings reveal complex interaction spheres extending across hundreds or even thousands of kilometers, highlighting the economic and social impact of bronze metallurgy.

Archaeological Evidence of Early Metalworking

Artifacts and Production Debris

The archaeological record of early metalworking includes finished artifacts, production debris, and associated installations. Common copper and bronze artifacts include axes, daggers, spearheads, pins, and ornaments. The presence of slag, crucibles, molds, and tuyères provides direct evidence of smelting and casting activities.

Microscopic analysis of metal artifacts reveals hammer marks, casting seams, and evidence of repeated annealing. These traces allow archaeologists to reconstruct manufacturing sequences and assess the skill levels of early metalworkers.

Mining Landscapes

Mining sites offer critical insights into the scale and organization of early metallurgy. At sites such as Rudna Glava in Serbia and Great Orme in Wales, archaeologists have documented extensive prehistoric mining operations. Stone hammers, antler picks, and wooden supports attest to the labor-intensive nature of early mining.

The organization of mining suggests coordinated efforts involving multiple individuals, possibly under centralized control. Such activities likely required social structures capable of mobilizing labor and managing resource distribution.

Dating Methods in Early Metallurgy

Radiocarbon Dating

Radiocarbon dating remains one of the primary methods for establishing the chronology of early metallurgy. Charcoal from furnaces, mining debris, and associated habitation layers provides material suitable for dating. When carefully contextualized, radiocarbon dates can establish the timing of metallurgical activities with reasonable precision.

Archaeometallurgical Analysis

Advances in archaeometallurgy have revolutionized the study of early metals. Techniques such as lead isotope analysis, X-ray fluorescence, and metallography allow researchers to determine the composition and provenance of metal artifacts. These methods help distinguish between local production and imported items, shedding light on trade and technological transmission.

Stratigraphy and Typology

Stratigraphic analysis and artifact typology remain essential tools in dating early metalworking contexts. Changes in tool forms, alloy composition, and manufacturing techniques can be traced over time, providing relative chronologies that complement absolute dating methods.

Cultural and Social Significance

Transforming Economies and Labor

The adoption of metallurgy transformed economic systems by introducing new forms of specialization. Metalworkers required extensive training and access to raw materials, leading to the emergence of craft specialists. Control over metal production and distribution often conferred social power, contributing to increasing social stratification.

Metal tools enhanced agricultural productivity, supporting population growth and urbanization. Improved weapons altered patterns of conflict and defense, influencing political organization and territorial expansion.

Symbolism and Identity

Beyond their practical uses, metal objects carried symbolic meanings. Copper and bronze artifacts were frequently deposited in burials, hoards, and ritual contexts. Their association with prestige, authority, and supernatural power is evident in many early societies.

The distinctive appearance and durability of metal objects made them ideal markers of identity and status. In some cultures, metallurgical knowledge itself was imbued with ritual significance, with metalworkers occupying ambiguous positions as both skilled artisans and holders of esoteric knowledge.

Impact on Human Evolution

While metallurgy did not alter human biology directly, it profoundly shaped the evolutionary trajectory of human societies. The technologies and social structures enabled by metalworking facilitated larger, more complex communities, accelerating cultural evolution. In this sense, the first metalworkers played a crucial role in shaping the environments to which humans adapted.

Key Discoveries and Scholarly Interpretations

The Balkans and the Earliest Smelting Evidence

Discoveries in the Balkans have challenged earlier assumptions that metallurgy originated solely in the Near East. Sites such as Belovode and Pločnik provide early evidence of copper smelting and complex metalworking traditions in southeastern Europe. These findings suggest a more pluralistic model of metallurgical origins, involving multiple centers of innovation.

Mesopotamia and the Bronze Age World

In Mesopotamia, the widespread use of bronze coincided with the rise of early states and urban centers. Archaeological evidence from cities such as Ur and Uruk demonstrates the integration of metalworking into administrative and economic systems. Written records from later periods attest to the regulation of metal production and trade, underscoring its importance to state power.

Ongoing Debates

Scholars continue to debate the extent to which metallurgy spread through diffusion versus independent invention. While similarities in techniques suggest knowledge transfer, regional variations indicate local experimentation and adaptation. Current research emphasizes the role of social and environmental factors in shaping metallurgical practices.

Modern Research and Future Directions

Experimental Archaeology

Experimental archaeology has provided valuable insights into early metallurgical techniques. By reconstructing furnaces, tools, and processes using traditional materials, researchers can test hypotheses about temperature control, fuel efficiency, and production yields. These experiments help bridge the gap between archaeological remains and lived practices.

Interdisciplinary Approaches

Modern studies of early metallurgy increasingly draw on interdisciplinary collaboration. Geology, chemistry, anthropology, and materials science contribute to a more nuanced understanding of ancient metalworking. High-resolution analytical techniques continue to refine chronologies and trace exchange networks with unprecedented accuracy.

Preservation and Ethical Challenges

Many early metallurgical sites face threats from modern mining, development, and looting. Preserving these landscapes is essential for understanding humanity’s technological heritage. Ethical considerations also arise in the study and display of metal artifacts, particularly those recovered from burial context.