A study by Dr. Mahdi Alirezazadeh and Dr. Hanan Bahranipoor, published in Archaeological Research in Asia, presents the analysis of two exceptionally well-preserved fetal burials from Chaparabad, Iran, dating to the mid-5th millennium BC. Among them is burial L522.1, one of the most complete prehistoric infant burials ever documented on the Iranian Plateau. Although the two fetuses were buried only a few meters apart, they exhibit markedly different burial treatments, offering valuable insight into the diversity of prehistoric mortuary practices in southwestern Asia.

Fetal burials

Fetal burials are occasionally encountered during archaeological excavations but remain relatively rare in the archaeological record due to poor preservation conditions. Nevertheless, evidence of fetal burial practices has been documented from the Neolithic through the Chalcolithic periods across Southwest Asia, including the Fertile Crescent and the Central Plateau of Iran.

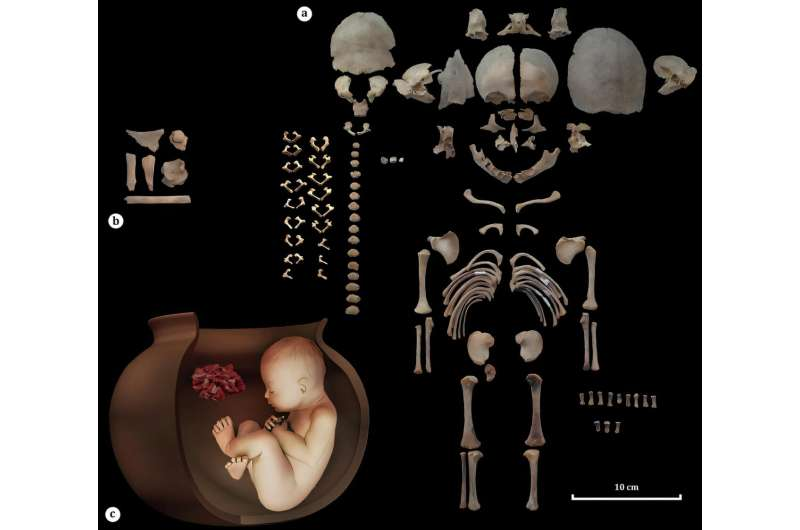

Excavations at Chaparabad conducted between 2021 and 2023 uncovered two fetal vessel burials, designated L522.1 and L815.1. Both were located within an architectural space measuring approximately 310 square meters. Burial L522.1 was recovered from Structure D, interpreted as a kitchen, while L815.1 was found in a space likely used for storage. In both cases, the fetuses were interred in ceramic vessels associated with the Dalma culture of the early 5th millennium BC.

“The burial vessels appear to have been previously used for everyday domestic activities,” explains Dr. Alirezazadeh. “For instance, the vessel associated with L522.1 is a Red Slip Ware typical of the Dalma cultural tradition, and smoke staining on its exterior indicates it had likely been used for cooking.”

Together with other ceramics from the site belonging to both the Dalma and the Pisdeli (late 5th millennium BC) cultures, the evidence suggests that the burials occurred during a period when both cultural traditions were contemporaneously active in the region.

Skeletal analysis and burial treatment

The exceptional preservation of the remains—particularly burial L522.1, for which approximately 90 percent of the skeletal elements were recovered—allowed for detailed quantitative and qualitative analyses. Based on bone fusion and long bone measurements, both fetuses were estimated to have died between 36 and 38 weeks of gestational age.

No clear signs of trauma were identified, with the exception of a fracture to the right parietal bone of L522.1. Given the positioning of the skull near the rim of the vessel, researchers concluded that the fracture most likely resulted from soil pressure during or after burial rather than perimortem injury.

Despite their close spatial proximity and similar developmental age, the two burials differed significantly in treatment. Burial L522.1 was accompanied by grave goods, including ovicaprid (sheep or goat) remains placed both inside the vessel near the rim and beneath it, as well as a worked stone found nearby. In contrast, L815.1 contained no grave goods and was buried outside the kitchen area, within a storage space.

According to Dr. Alirezazadeh, this contrast reflects broader regional patterns of variability in fetal and infant burial practices during the Dalma and Pisdeli periods. Archaeological parallels demonstrate wide-ranging approaches to burial vessels and grave goods. At Chagar Bazar in Syria, fetal burials used vessels ranging from weaning bowls to miniature pots, while at Tell as-Sawwan, burials were typically sealed with inverted bowls and ceramic fragments. Grave goods also varied considerably: a fetus at Girdi Sheytan was buried with stone beads, three copper axes accompanied a burial at Ovçular Tepesi, and at Yarim Tepe—near the Dalma cultural sphere—all 14 known fetal burials lacked grave goods entirely.

This variability is mirrored at Chaparabad. “The two burials were discovered less than three meters apart and belong to the same chronological horizon,” Dr. Alirezazadeh notes. “This allows us to rule out explanations based on broader cultural differences or social hierarchy.”

However, he emphasizes the limitations of interpretation: “We did not live within these communities, and therefore cannot state with certainty why one infant received burial goods while the other did not. Our conclusions are necessarily constrained by the available data, and further research will be required.”

Ongoing DNA and stable isotope analyses may provide additional insights into kinship, health, and social practices. Overall, the Chaparabad fetal burials highlight the complexity of prehistoric mortuary behavior and underscore the cultural significance attributed to fetal individuals in Chalcolithic societies of the Iranian Plateau.