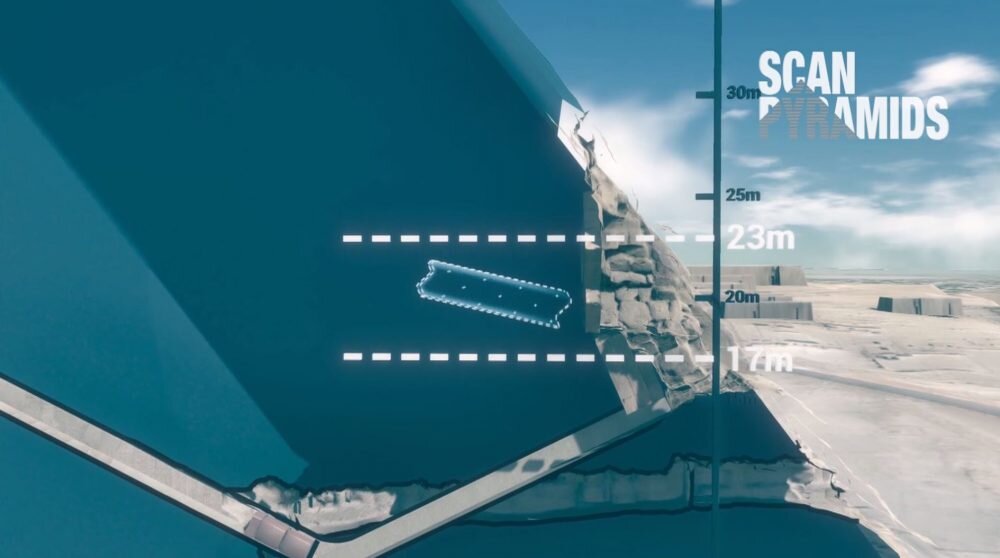

In 1978, Japanese researchers conducted several studies with the aim of proving that the ancient Egyptians built the pyramids by the primitive method of construction, which consisted of cutting stones with chisels and stacking them by lifting ropes and other manual means.

With direct funding from Japanese TV, the Japanese decided to go through the experiment and rebuild a new pyramid in Giza through primitive means. The research team began its work, where the two parties agreed that the entire experiment would be transformed into a documentary film for Japanese TV, in agreement with the Egyptian government, provided that The small "experiment" pyramid is removed after it is completed and the area is completely cleaned up and returned to what it was.

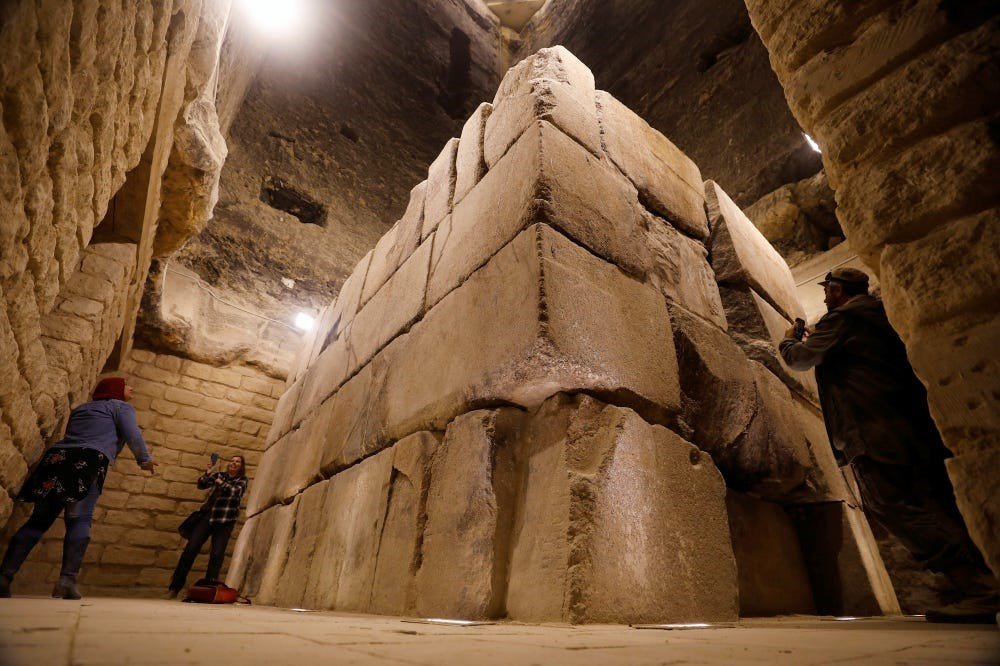

The initial planning of the experiment stipulated that a 20-meter-long pyramid would be built using terraces, with each stone weighing 4 tons. Now - and to involve 100 Egyptian workers to implement the experiment.

Despite all the technological progress available at the time of implementing the Japanese experiment in 1978 compared to what was available thousands of years ago when building the Great Pyramid, and despite the brilliant minds that participated in the study and implementation of the experiment from scientists in several fields, the team was exposed to several confusing shocks during the experiment.

In the beginning, the team found that the issue of cutting stones each weighing 4 tons using primitive tools such as chisels and others is very difficult, and requires a huge cost and a very long time, so they only had to reduce the height of the pyramid to be implemented from 20 to 10 meters only, and reduce the weight of the stone From 4 to 1 ton only, and the use of electric saws in the process of cutting stones, which was the first use by them of modern technological means in violation of the main objective of the experiment, which is to prove the ability of primitive tools to build a pyramid the size of the Great Pyramid.

Then the team discovered the failure of all means, the beginning of transporting stones from Tora to the Giza plateau via the Nile, such as the idea of floating on wooden rafts or even boats, so they used the technology for the second time through the use of flat ships that carry the weight of the stones and move them in the waters of the Nile.

When the stones reached the shores near the pyramid, about 50 workers could not move one stone but several centimeters, which means that the experiment could have taken several years only to be able to transport the stones from the Nile River to the place of construction, so they had to extend a railway Small iron carts pass by, each carrying one stone.

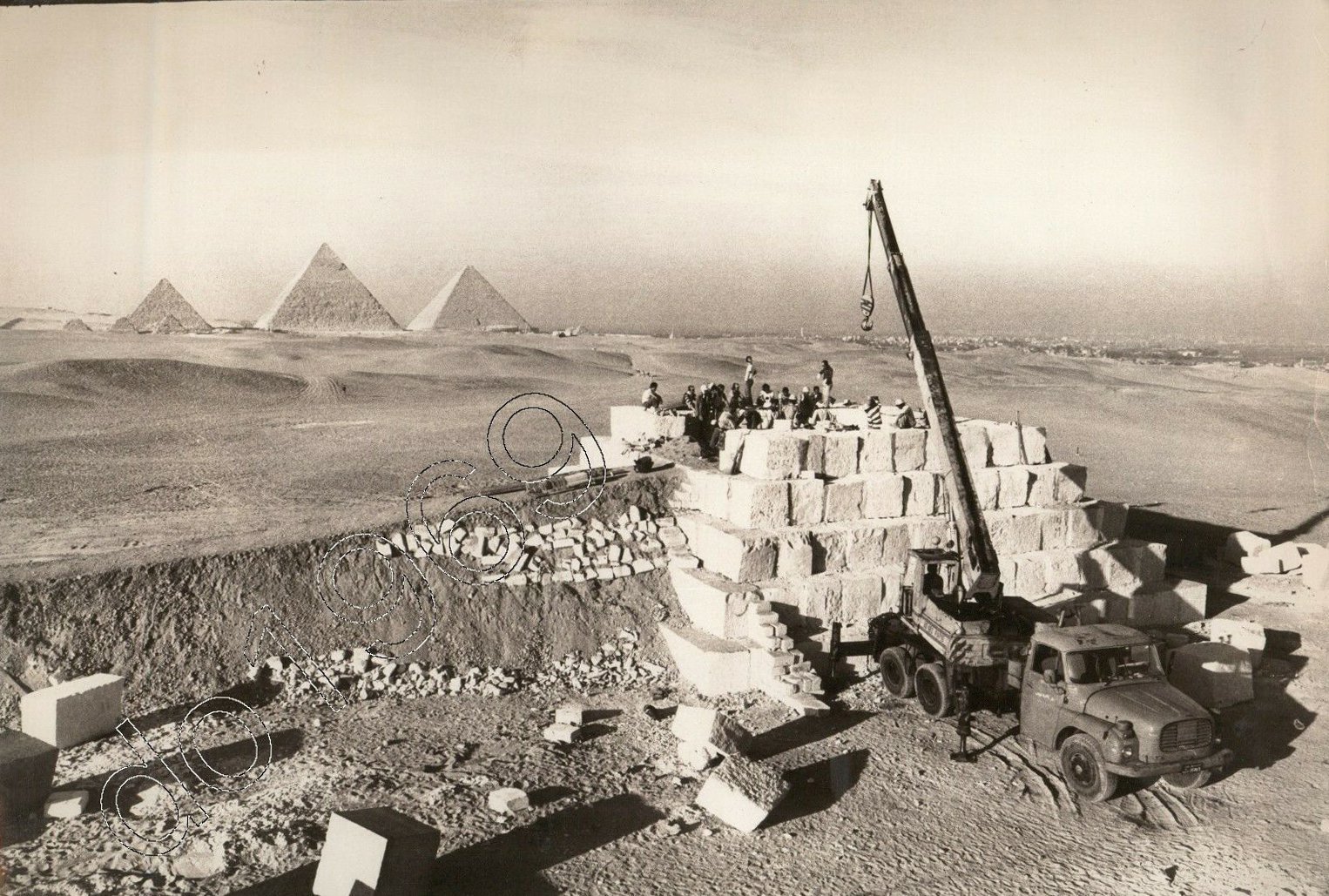

After these difficulties as a result of the huge weight of the stones, they naturally expected the difficulty of the next step of lifting the stones and placing them in the allotted place inside the floor of the pyramid, which prompted them to use large cranes and cranes to stack the stones, and even the matter came to them to use a helicopter To set the stones precisely in their places!

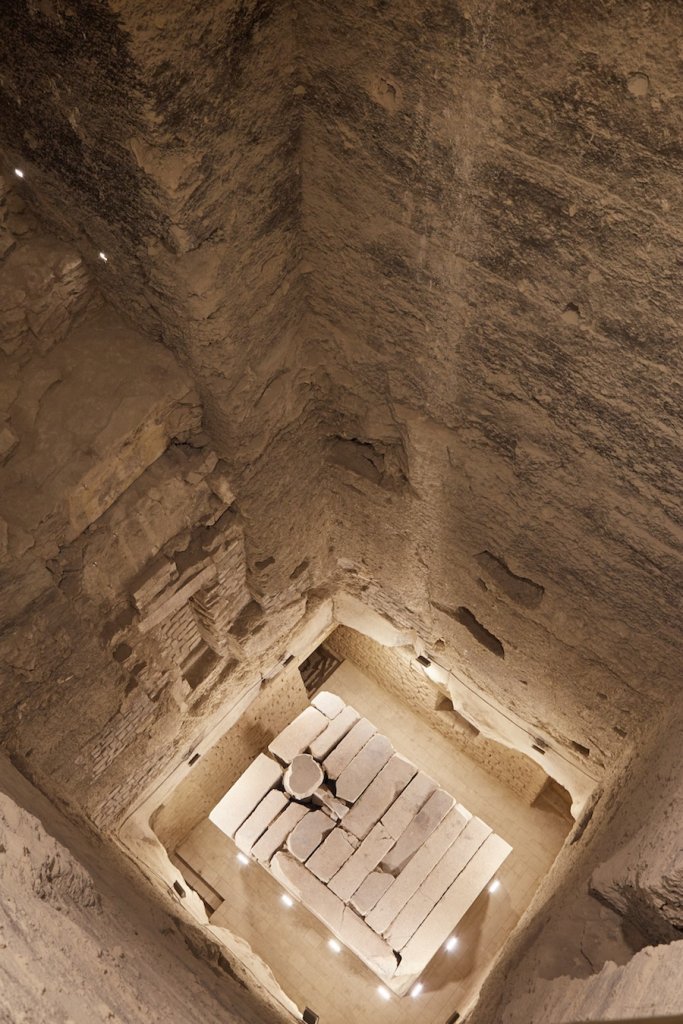

Although the team eventually managed to build a 10-meter pyramid in the exact location next to the Giza pyramids, the experiment proved to be a failure by all standards, after the team had to use more than one technological means to complete the construction process.

Which means, by extension, the incorrectness of most of the traditional theories that were said in the construction of the pyramids, which depended in the construction process on the old primitive traditional tools, after practical experience proved the impossibility of that.