Archaeologists working at the Sissi site in northern Crete have uncovered compelling evidence of a 4,000-year-old ritual that marked the symbolic end of a burial ground—and possibly, the community’s way of life as they knew it.

The discovery comes from a section known as Zone 9, where researchers found signs of an elaborate ceremony involving the final burials, destruction of tombs, and a massive communal feast. This ceremony, archaeologists believe, wasn’t just about honoring the dead—it was about closing a chapter of collective memory.

A Last Celebration in the Cemetery

In this final act of funerary ritual, the people of Sissi buried their last dead in small pits and ceramic vessels. Then, in what appears to be a deliberate and symbolic gesture, they dismantled the walls of the tombs, broke some bones to level the remains with the earth, and hosted what can only be described as a large communal feast.

The evidence? A thick layer of soil littered with thousands of ceramic fragments, including cup and plate shards, all dated to around 1700 BCE. According to researchers, these weren’t trash or random refuse. They were remnants of a carefully staged ritual meal, a way for the community to say farewell—not just to their dead, but to the era of communal burials itself.

After the celebration, the area was sealed with a layer of earth and stones, effectively closing the cemetery. Interestingly, when burials resumed in the area centuries later, the space was treated with unusual reverence, almost as if it had become sacred or forbidden.

Why Were the Tombs Destroyed?

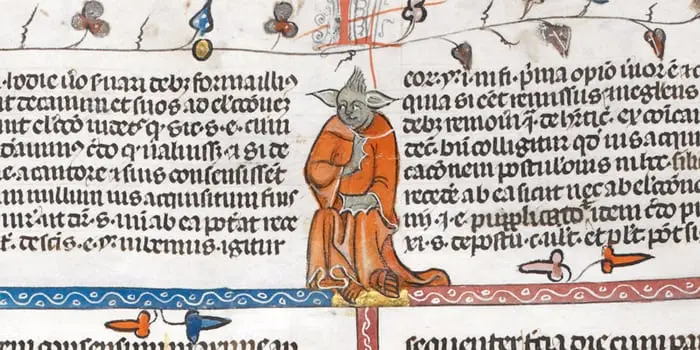

Room 9.6, containing clay vessels FE147, FE148, and FE149 (left), and details of the clay vessels during excavation (right). Photo: N. Kress, A. Schmitt / Belgian School at Athens.

This wasn’t an act of neglect or vandalism—it was a response to profound social and cultural shifts, say archaeologists. Around the same time, the first Minoan palaces, like that of Knossos, began to rise, signaling a transition to more centralized political and religious systems.

Traditional communal tombs, often tied to clans or extended families, began to lose their significance. In their place, new ceremonial spaces emerged, such as mountain sanctuaries and sacred caves.

By ritually “burying” their own cemetery, the people of Sissi weren’t rejecting their past—they were honoring it, embedding it in collective memory. As the researchers put it, their message was clear: “This way of burial no longer defines us—but we won’t forget it.”

A Broader Minoan Practice?

Sissi isn’t the only site where similar practices have been found. In southern Crete, at Moni Odigitria, a circular tomb was emptied, its contents reburied in a pit alongside hundreds of broken cups. At Kefala Petras, some tombs were filled with stones, a practice archaeologists interpret as a symbolic ‘killing’ of the tomb.

However, not all Minoan cemeteries were closed this way. Some simply fell out of use, while others remained active as ritual spaces rather than burial sites. This variation suggests that each community responded differently to the same sweeping cultural changes.

A Ritual for the Living, Too

What makes the Sissi discovery so exceptional is the level of detail preserved. Using modern techniques—such as bone analysis and stratigraphy—archaeologists were able to reconstruct the sequence of events: from the last burials, to the final feast, to the moment the cemetery was sealed forever.

In the past, many Minoan cemeteries were excavated quickly, with limited documentation. Now, thanks to meticulous fieldwork, it’s becoming clear that farewell rituals were likely far more common than once thought.

These ceremonies weren’t only for the deceased. As archaeologists point out, they were also deeply meaningful for the living—a way to come together in times of uncertainty and declare:

“This is who we are now.”