In a major scientific breakthrough, researchers have uncovered the unexpected ancestry of a group of mysterious desert mummies found in northwestern China. For decades, these naturally preserved remains puzzled archaeologists and historians, but now, ancient DNA has shed new light on who these people really were.

A Mystery Buried in the Sand

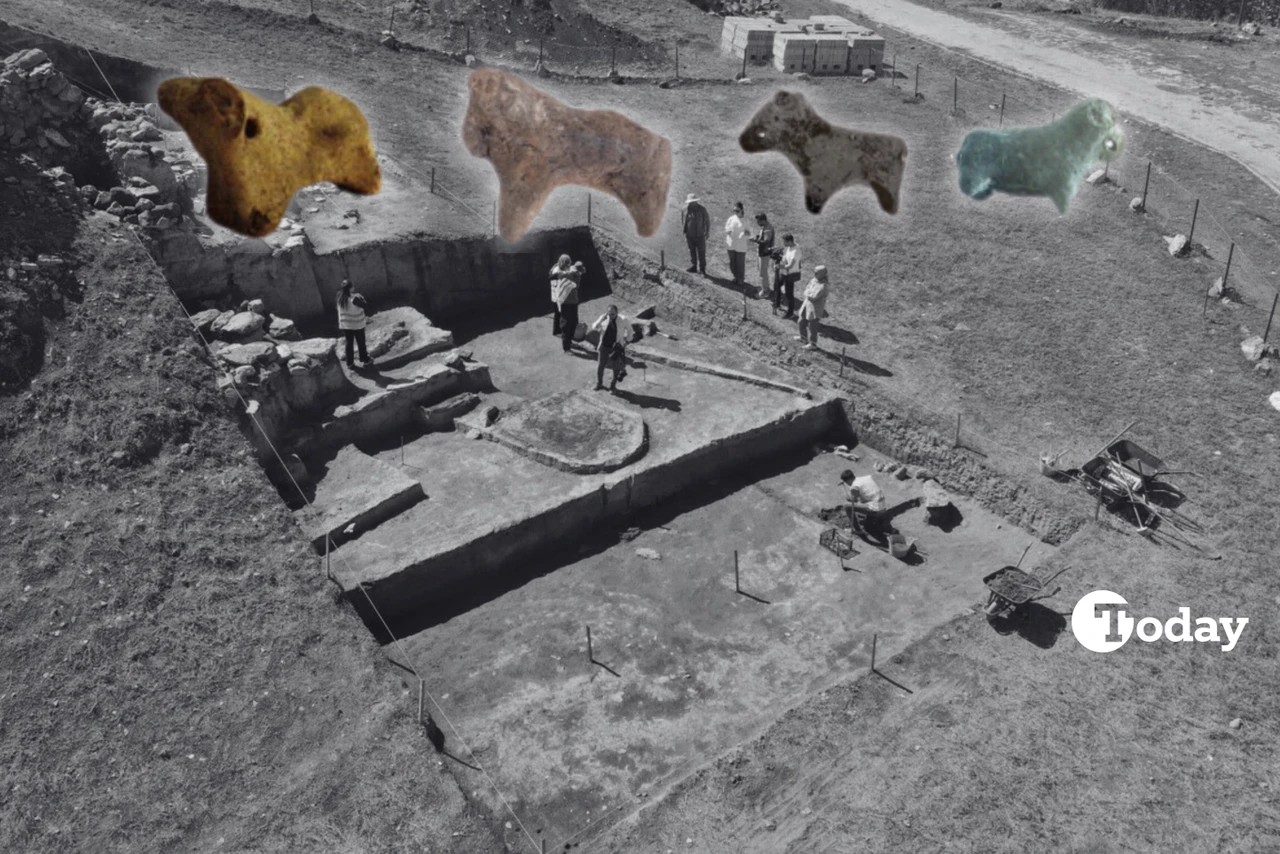

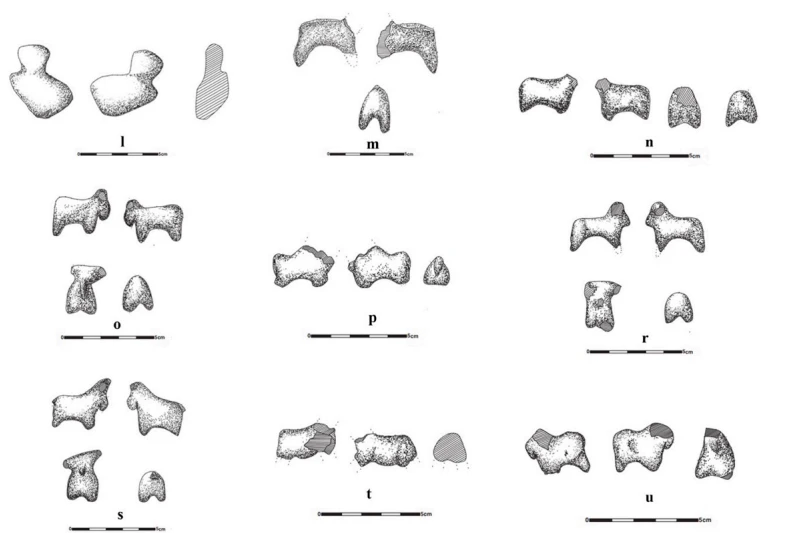

Since their discovery, the origins of hundreds of remarkably preserved mummified bodies buried in wooden boat-like coffins in the harsh desert environment of China’s Tarim Basin, in Xinjiang Province, have sparked debate among scientists. Unearthed primarily in the 1990s, these mummies are estimated to be around 4,000 years old, yet their clothing, bodies, and burial artifacts remain astonishingly intact.

Their Western facial features, finely woven woolen garments, and unusual grave goods—like cheese, wheat, and millet—initially led researchers to believe they were herders from the western steppes of Asia or farmers from Central Asia’s mountainous oases.

But a comprehensive DNA analysis has turned that theory on its head.

A 4,000-Year-Old Genetic Revelation

A team of scientists from China, Europe, and the United States examined the DNA of 13 of these mummies. To their surprise, the results showed that the remains did not belong to newly arrived outsiders. Instead, the mummies were the descendants of a long-isolated local population linked to an ancient Ice Age lineage in Asia.

“These mummies have captivated scientists and the public alike ever since they were found,” said Christina Warinner, associate professor of anthropology at Harvard University. “Not only are they exceptionally well-preserved, but they were buried in a highly unusual context, displaying diverse and far-reaching cultural elements.”

Warinner, who is also head of the microbiome sciences group at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and lead author of the study published in Nature, added: “Our findings show strong evidence that they represent an extremely genetically isolated local population.”

Isolated Yet Culturally Connected

Despite their genetic isolation, these ancient people appeared to embrace new ideas and technologies from neighboring herders and farmers. At the same time, they maintained a distinct cultural identity, developing burial customs and traditions not seen in any other known civilization.

The research team also analyzed genomes from five individuals found further north in the Dzungarian Basin, also in Xinjiang. These remains, dating back 4,800 to 5,000 years, are the oldest human remains ever found in the region.

Ancient DNA: A Window Into the Past

“Ancient DNA provides powerful clues about human migration in periods where written records or other evidence are scarce,” said Vagheesh Narasimhan, an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin who has studied genetic samples from Central Asia. Though not involved in this particular study, he called the findings “fascinating.”

The analysis revealed that the Tarim Basin mummies were direct descendants of a group known as the Ancient North Eurasians, a population that was once widespread during the Ice Age but had mostly disappeared by the end of that period, around 10,000 years ago.

Today, only trace amounts of this group's genetic material remain, primarily among Indigenous populations in Siberia and the Americas.

Interestingly, the genetic samples from the Dzungarian Basin indicated those people had mixed extensively with Bronze Age populations in the region. In contrast, the Tarim mummies remained strikingly genetically isolated.

Culture Without Migration

“This research shows that genetics doesn’t always align with cultural or linguistic exchange,” explained Narasimhan. “People can adopt farming, metalworking, or burial practices from neighboring groups without necessarily intermingling or moving themselves.”

Michael Frachetti, an anthropology professor at Washington University in St. Louis who was not involved in the study, echoed this sentiment. “It’s paradoxical,” he noted. “We see a community that was culturally well-integrated—drawing from diverse traditions—yet genetically they remained remarkably distinct, preserving a lineage that goes far back in time.”

Frachetti added that during the Bronze Age, this region was a vibrant crossroads of civilizations. “There was intense mixing of cultures from the north, south, east, and west as far back as 5,000 years ago.”

Unanswered Questions Remain

While this study has clarified many aspects of the mummies’ genetic background, it also opens the door to new questions. The research focused on mummies from a single site within the Tarim Basin. It’s unclear whether other areas of the region might reveal different genetic connections.

“The origin of this burial tradition remains one of the great mysteries of these desert people,” Frachetti said. “They may well be the last community in the world to practice it.”

Final Thoughts

These findings challenge long-standing assumptions and highlight the complexity of ancient human history. The Tarim Basin mummies were not foreign migrants, but rather descendants of an ancient, isolated lineage that nonetheless embraced cultural diversity. Their story underscores how human societies can remain rooted in their ancestry while engaging dynamically with the world around them.