Long before they were trapped in lamps and summoned with wishes, Djinn—also spelled Jinn—were feared and revered spirits in the deserts of Arabia. Rooted in pre-Islamic mythology and later incorporated into Islamic belief, these enigmatic beings inhabit a world parallel to ours, made not of flesh or bone, but of "smokeless fire."

Unlike angels or demons in Western traditions, Djinn occupy a unique and ambiguous space in folklore: they are neither wholly good nor inherently evil. Instead, they possess free will, personalities, and powers that make them both divine and dangerously human.

Origins: Djinn in Pre-Islamic Arabia

Before the rise of Islam in the 7th century CE, the Arabian Peninsula was a land rich in oral storytelling and animistic beliefs. Among desert-dwelling tribes, the Djinn were seen as supernatural forces of nature—spirits who lived in remote or wild places like:

Deserts and sandstorms

Ruins and mountains

Dark caves and abandoned wells

People believed Djinn could possess humans, inspire poets, or protect certain places. Some were benevolent, while others were malicious tricksters, blamed for illness, madness, or misfortune.

Travelers and storytellers would share tales of Shayatin (evil djinn) and ifrits—fiery spirits known for their ferocity. Offerings and protective charms were used to keep them at bay.

Djinn in Islamic Tradition

The Qur’an redefined the Djinn while preserving their mysterious essence. According to Islamic theology, Djinn are one of three intelligent beings created by God:

Angels (made of light)

Humans (made of clay)

Djinn (made of smokeless fire)

Djinn are mentioned frequently in the Qur’an and Hadith (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad). They are born, marry, have children, and will die, just like humans. Crucially, they are also accountable to God and capable of choosing belief (Muslim Djinn) or disbelief (Kafir Djinn).

"And I did not create the jinn and mankind except to worship Me."

— Qur’an 51:56

The most famous Djinn in Islamic lore is Iblis, a proud jinn who refused to bow to Adam and was cast out of Paradise, becoming Shaytan (Satan). This story marks a shift in understanding Djinn not only as wild spirits but also as moral beings engaged in the cosmic struggle between good and evil.

Types of Djinn in Folklore

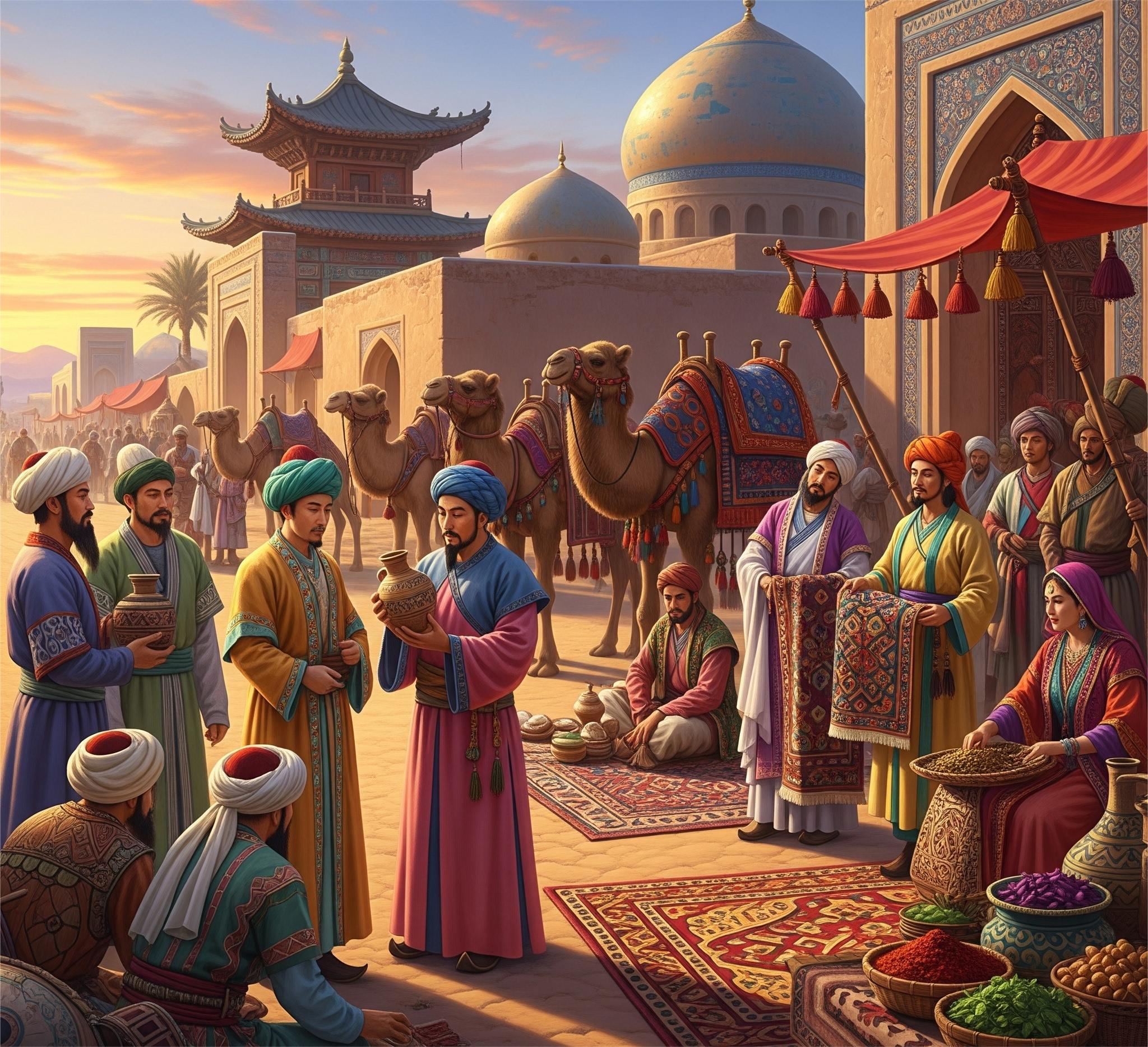

Over time, Islamic and local traditions across the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia expanded on the concept of Djinn, developing distinct categories and names:

Ifrit: Powerful and malevolent fire spirits, often associated with vengeance or destruction

Marid: Strong, often rebellious Djinn, sometimes portrayed as sea spirits who grant wishes—but at a cost

Shayatin: Evil spirits aligned with Iblis, sowing discord and whispering temptation

Ghoul (Ghul): Desert-dwelling shape-shifters who feed on human flesh and haunt graveyards

Sila & Qareen: Djinn that can take human form, with the Qareen believed to accompany each person, influencing their thoughts and actions

These diverse types reflect centuries of regional beliefs, superstitions, and cross-cultural exchanges blending Islamic theology with ancient Mesopotamian, Persian, and Bedouin ideas.

Djinn in Popular Culture

Thanks to stories like The Arabian Nights (One Thousand and One Nights), Djinn entered global imagination as genies—magical beings that grant wishes to the lucky (or cursed) soul who frees them. These tales romanticized and simplified the Djinn, but retained their capricious nature.

In the West, the image of the Djinn was further shaped by:

Disney’s Aladdin, featuring a blue, comedic genie

Horror films like Under the Shadow and Djinn, which return to their darker folkloric roots

Literature such as Neil Gaiman’s American Gods or Helene Wecker’s The Golem and the Jinni, which explore their complexities

However, in many Muslim cultures today, belief in Djinn remains very real. People still recite verses like Ayat al-Kursi for protection, and traditional healers may perform ruqyah (spiritual exorcisms) to expel harmful Djinn.

Djinn as Metaphor: Between Worlds

The Djinn represent much more than spirits—they are reflections of the unseen, of fears and desires that defy logic. Their stories speak to:

Mental health (madness attributed to possession)

Power dynamics (subjugation, servitude, and rebellion)

Cultural identity (how different societies grapple with the unknown)

They challenge the lines between natural and supernatural, good and evil, and even free will and destiny. As such, Djinn endure not just as characters of myth, but as symbols of the hidden energies that shape human life.