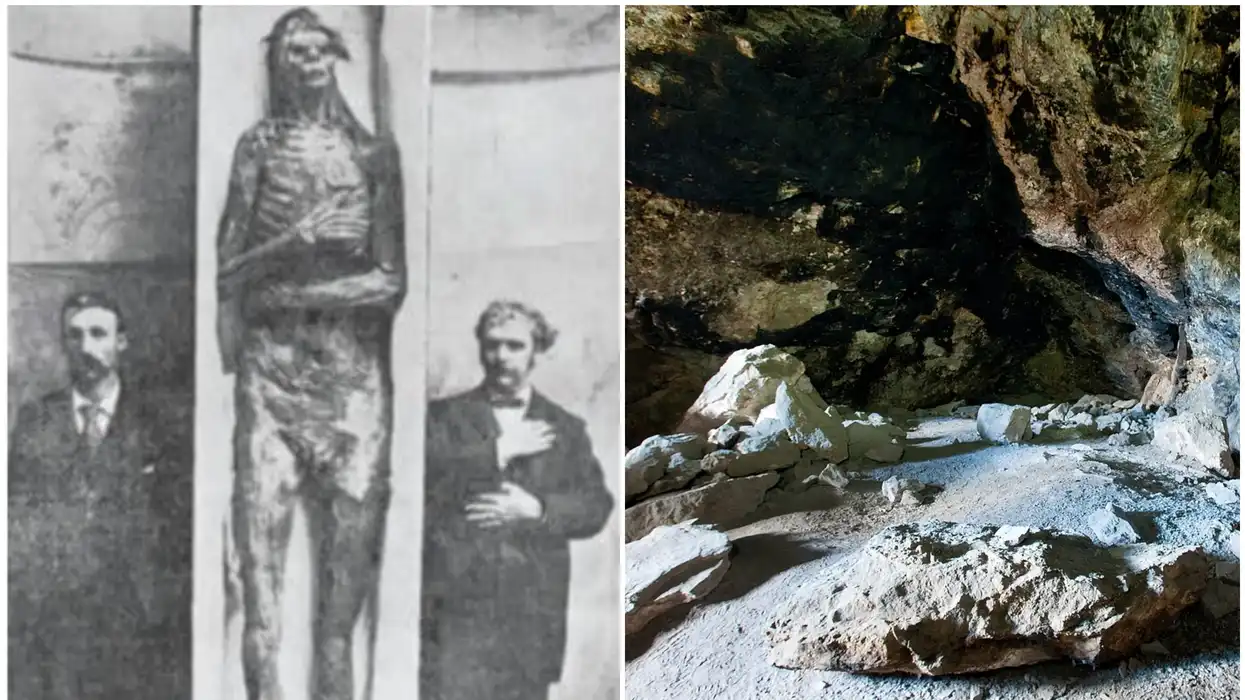

There is no verified scientific evidence that a race of 8–10-foot-tall red-haired giants once lived in Nevada or anywhere else in the Americas. The Lovelock “giants” story is a mix of Paiute oral tradition, early 20th-century newspaper exaggeration, and later sensational retellings.

Now let’s unpack what actually happened.

In 1911, miners digging for guano in a cave near Lovelock uncovered artifacts and human remains. This site, now known as Lovelock Cave, was later excavated formally in 1912 and 1924. Thousands of artifacts were recovered — tools, sandals, duck decoys, textiles — and they are considered important finds in Great Basin archaeology.

The Paiute oral tradition speaks of red-haired beings called the Si-Te-Cah, described as enemies who arrived on reed rafts and were eventually defeated. That legend is real and culturally significant.

What about the giant skeletons?

Here’s where it gets murky:

No 8–10-foot skeletons from Lovelock Cave exist in museum collections.

No peer-reviewed archaeological reports confirm such heights.

Early newspaper articles (like one from the Nevada Review-Miner in 1931) made dramatic claims, but those reports were never substantiated scientifically.

Human hair can turn reddish after death due to chemical changes — which may explain the “red hair” description.

As for Pedro Cieza de León — yes, he recorded Indigenous legends in 16th-century Peru about giants arriving by sea. But explorers frequently documented local myths without verifying them as biological fact.

Archaeologically speaking, the human remains from Lovelock Cave that have been studied fall within normal human height ranges for the time. There’s no credible evidence of a separate race of giants dominating southwestern America.

That doesn’t make the story boring, though. It’s actually more interesting.

What we’re looking at is:

Indigenous myth preserved over generations

Early sensational journalism

A real archaeological site with real cultural importance

And modern internet amplification

Mythology across cultures — including Biblical Nephilim stories — often features giants. That tells us something powerful about human storytelling and symbolism. But symbolism isn’t the same as skeletal proof.

If you want, we can dive into:

The Paiute version of the Si-Te-Cah story

How giant myths appear across cultures

Or how early 1900s archaeology sometimes fueled sensational claims

The Paiute people were said to have fought back after years of being terrorised and cannibalised by the Si-Te-Cah

Alright — let’s slow this down a little, because this is where myth and archaeology get tangled together again.

Yes, elongated skulls have been found in the Andes, particularly around the Lake Titicaca region between Peru and Bolivia. Many of these remains date back thousands of years.

But here’s the key thing:

Those skull shapes are the result of intentional cranial modification, not a separate species or a race of giants.

Ancient Andean cultures — like the Paracas and others — practiced head binding, where a child’s skull was gently shaped over time using boards or cloth. The skull bones of infants are soft and can be molded. This was a social or cultural marker — often tied to status, identity, or beauty — not biology.

Now about the size claims.

There’s no verified scientific evidence that these skeletons were dramatically larger than normal humans. And as for the red hair? That part actually has a very mundane explanation: human hair can turn reddish after burial because dark pigments break down over time. It’s a chemical change, not proof of ancestry.

The Si-Te-Cah legend from the Paiute is powerful and meaningful — but it’s oral tradition, not forensic documentation. Many cultures tell stories of giant enemies or ancient powerful beings. These stories often symbolize conflict with rival groups, outsiders, or earlier populations. Over generations, those enemies become “giants” in memory — bigger, stronger, more monstrous.

And the ending of the story — where tribes unite to defeat them — fits a classic mythic structure. It’s about survival, unity, and identity.

Here’s the grounded takeaway:

Elongated skulls = cultural practice

Red hair = post-burial chemical change

Giant skeleton claims = not supported by verified museum evidence

Si-Te-Cah = important mythology, not proven biological population

It’s totally understandable why these stories feel compelling. Giants appear in the Bible, in Greek myths, in Norse legends, in Mesoamerican stories — everywhere. Humans have always told stories about beings larger than life.

But so far? No credible archaeological evidence supports the existence of a 8–10 foot red-haired race in the Americas.