The dating of the Minoan eruption of Thera has been one of the most stubborn archaeological headaches in Aegean prehistory. The problem is not that we do not know it happened in the Late Minoan IA period. The problem is that everyone wants to pin it precisely onto the Egyptian timeline. Which pharaoh’s world did it shake. Ahmose. Thutmose III. Someone else. The new study by Hendrik J. Bruins and Johannes van der Plicht in PLOS One turns one of the most popular scenarios upside down with a very clear message. The Thera eruption happened before Pharaoh Nebpehtire Ahmose, during the Second Intermediate Period. It did not take place during the reign of the founder of the 18th Dynasty.

What is interesting here is that this is not just another “new number” in years BCE. It is a targeted attempt to reexamine older theories using Egyptian finds that, for the first time, are radiocarbon dated and directly compared to the existing 14C package for the Thera eruption.

The older theories under the microscope

For a long time, the “traditional” view in Aegean archaeology was roughly this. The Thera eruption occurred around 1500 BCE, somewhere in the early 18th Dynasty. Many researchers tried to connect it either with the era of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III, or with Ahmose, the king who expelled the Hyksos and reunified Upper and Lower Egypt.

On top of this came the famous “Tempest” of Ahmose. The inscription of the so called Tempest Stela at Karnak describes a terrifying storm with darkness and destruction. Some scholars read it as an environmental echo of the Thera eruption, almost like an ancient “live report” on its meteorological consequences.

At the same time, from the 1980s onward, radiocarbon dating began to push Thera stubbornly toward the 17th century BCE. In other words, before the classic early 18th Dynasty, inside the Second Intermediate Period. This trend was strengthened by tree ring series and statistical analyses by Manning and others, which pointed to a likely eruption date around 1600–1580 BCE, with small variations depending on the version of the IntCal calibration curve used each time.

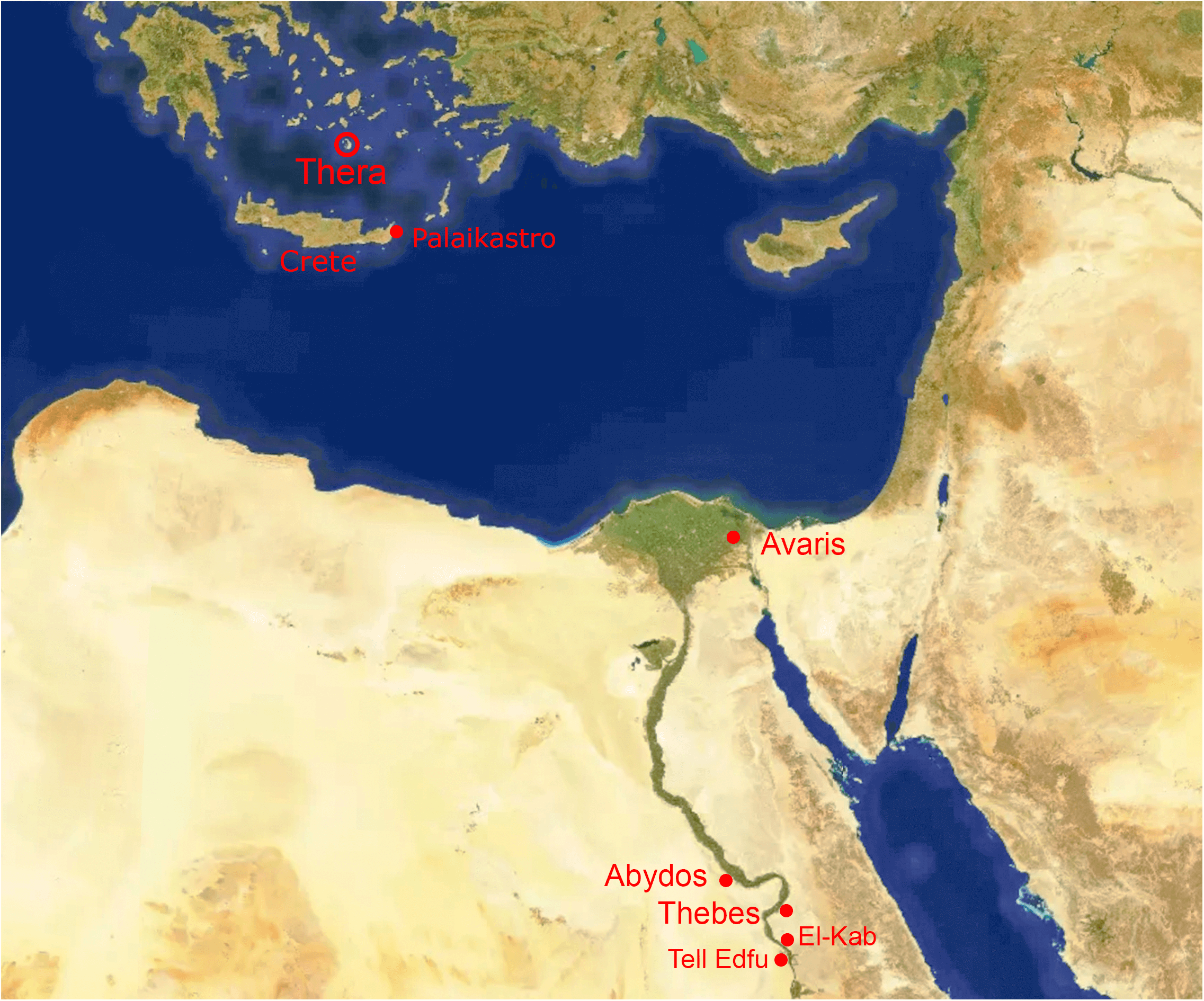

The problem was that while we had a fairly coherent 14C package for the Thera eruption itself, from Akrotiri, an olive branch, Palaikastro and so on, we did not have direct radiocarbon dates for the Egyptian side of the equation, specifically for the time of Ahmose. His chronology rested on reconstructions from king lists, Manetho, papyri, synchronisms with other regions, and heavy Bayesian models that, crucially, did not include any samples tied directly to Ahmose or the immediately preceding rulers.

This is exactly where the new study strikes. It does not try to re date Thera itself. Instead, it tests the Egyptian side and, quite literally, asks that “Ahmose too be put in the machine”.

The ancient remains that went into the AMS

Bruins and van der Plicht achieved something rare. They secured permission from the British Museum and the Petrie Museum to take small destructive samples from organic materials directly linked to the transition from the 17th to the early 18th Dynasty.

The three main “protagonists” are the following.

First, an unbaked mudbrick from the temple of Ahmose at Abydos, stamped with his throne name Nebpehtire. This is the key object that literally bears the king’s signature at the center of the debate.

Second, a linen burial cloth associated with Queen Satdjehuty, the second wife of 17th Dynasty king Seqenenre Tao, that is, just a few steps before Ahmose.

Third, six wooden “stick shabtis” from Thebes in the Petrie collection, named for people of the late 17th and early 18th Dynasty. Among them is a figure linked to the official Teti mesu, known from the tomb TT15 of the mayor Tetiky during the reign of Ahmose and Amenhotep I.

Tree rings are clearly visible in the bottom part of Shabti UC 40184 (diameter 3.1 cm).

The mudbrick from Ahmose’s temple is arguably the most critical piece. Archaeological research at Abydos has clearly shown that the temple and pyramid complex of Ahmose were built after his victory over the Hyksos, around the twenty second year of his reign. If we can date the straw mixed into the mud, we come very close to the actual time that this twenty second regnal year falls on the timeline.

The linen from Satdjehuty’s burial adds an independent chronological point from the funerary context of the Theban court. The wooden shabtis, carved from sycomore fig, offer a series of points through the late 17th and early 18th dynasty, with names that can be placed into the historical sequence of Thebes.

How the scientists worked. Radiocarbon, calibration curves and “time signatures”

The samples were measured at the Centre for Isotope Research in Groningen using AMS. Standard pre treatment was applied with acids and alkalis to remove contaminants, and the carbon in each sample was converted to graphite or measured as CO₂ in the case of very small samples. Results are reported in the conventional format of 14C years BP with standard deviation, and converted to calendar years using the IntCal20 calibration curve and the OxCal software.

However, the organic materials from Abydos and Thebes do not come from a neat stratigraphic sequence. They come from different monuments and objects that cannot be ordered in a clear line. That means the researchers could not build a Bayesian sequence model of the type used by Bronk Ramsey’s team for the Old and Middle Kingdom. There is simply no firm, agreed sequence with reign lengths and king order for that corner of the Second Intermediate Period that could be safely fed into the software.

Mudbrick EA 32689 (British Museum) from the Temple of Ahmose at Abydos, showing the same stamped prenomen Nebpehtire of Pharaoh Ahmose.

Bruins and van der Plicht chose a simpler and in some ways more robust approach. They start from the raw, uncalibrated radiocarbon dates. They work from the idea that if you take a sufficiently large and coherent set of 14C dates for event A, the Thera eruption, and a corresponding set for historical phase B, the transition from the 17th to the 18th Dynasty, then these two “bundles” will have distinct time signatures in 14C years BP. One will clearly be older than the other, regardless of how the calibrated dates move around on the IntCal curve as it gets updated over time.

For Thera they use three main data sets. They bring in thirteen radiocarbon dates from charred seeds in secure destruction layers at Akrotiri. They include the outer rings of the famous olive branch from Therasia, buried in the eruption deposits. They add dates from animal bones in the tsunami layers at Palaikastro in Crete, where the association with the Theran eruption and its tsunami is very clear.

The weighted means of these sets converge around 3340–3350 BP, with small errors. This is a clear package that is already familiar from the literature. Importantly, it does not seem to be distorted by any hypothetical “volcanic CO₂” effect at Thera, since the results from Crete and from Thera match closely.

Against this, the dates from the brick, the linen and the shabtis of the 17th–early 18th Dynasty come out systematically younger. The “pure” straw fragment from the Ahmose brick gives about 3230 ± 60 BP. The linen of Satdjehuty is around 3310 ± 25 BP. The shabtis range from 3300 to 3185 BP. When all of this is plotted together, the Thera cluster sits clearly older than the Egyptian cluster of the transition from the 17th to the 18th Dynasty.

What this means for the eruption and for Ahmose

The first conclusion is unusually clear for a topic like this. The Minoan eruption of Thera predates the reign of Nebpehtire Ahmose and the last rulers of the 17th Dynasty. In other words, there is no contemporary overlap between the eruption on Thera and Ahmose’s campaigns or the political reunification of Egypt that marks the start of the 18th Dynasty.

As a consequence, the scenarios that identified the Tempest Stela with the Thera eruption can be set aside. The study itself underlines that the climate of Upper Egypt is hyper arid. Severe rainstorms in the Theban region are extremely rare, and when they occur they are usually linked to the Red Sea Trough and the African monsoon system rather than to Mediterranean storms. The inscription of Ahmose probably describes an exceptionally rare but natural storm event. It is not a written echo of an Aegean super eruption.

The second, more technical, conclusion is that the dates from the Ahmose brick favor a low chronology for the start of the 18th Dynasty. In plain terms, Ahmose should not be placed on the throne around 1580 BCE, but rather somewhere in the 1540–1530 BCE range, in line with the model proposed by Bennett based on the genealogies of the governors of El Kab.

The radiocarbon date of the “pure” straw in the brick, which microscopic analysis identified as belonging to C4 plants of the Nile sedge or papyrus type, when calibrated with IntCal20, gives highest probabilities around 1500–1470 BCE for the construction of the temple at Abydos. This fits much better with the “lower” proposed dates for the twenty second regnal year of Ahmose than with the older, “high” chronologies for the start of the 18th Dynasty.

In parallel, the dates from the shabtis of Teti mesu and other individuals point in the same direction. These are funerary offerings placed at the end of Ahmose’s reign and into the time of Amenhotep I. They clearly fall later than the radiocarbon “package” for Thera, reinforcing the sequence.

A third key point is the connection to Bennett’s model for the governors of El Kab, who form a genealogical chain stretching from Senusert III of the 12th Dynasty to Amenhotep I. Bennett calculated a minimum time span of about 315 years between the seventh year of Senusert III and the first year of Ahmose. Combined with the 14C dates for Senusert III himself, this leads almost inevitably to a “high” chronology for the Middle Kingdom and a “low” chronology for the start of the New Kingdom. The new radiocarbon dates from the Ahmose brick and the shabtis fit perfectly into this framework.

What remains open, and what shifts in the bigger picture

This study does not give us a magical single year for the Thera eruption. The broader debate over whether the event should be placed in the early or mid sixteenth century BCE continues, with Bayesian models, tree ring chronologies and the quirks of the IntCal curve all playing their part.

What does change in a substantial way is our confidence that the eruption did not occur in the reign of Ahmose or in the final years of the 17th Dynasty, but earlier, during the Second Intermediate Period, when Egypt was still politically fragmented and the Hyksos controlled the north. The great Aegean volcanic disaster does not serve as the environmental “backdrop” for the birth of the New Kingdom. It belongs to an earlier, already turbulent era.

For Aegean archaeology this means that Late Minoan IA remains “high” relative to traditional Egyptian chronologies. The contacts between Minoans and Egyptians under the early 18th Dynasty need to be viewed as post eruption phenomena, belonging to the next phase of Minoan and Mycenaean history. For Egyptology it means that the Second Intermediate Period was longer and more substantial than some older compressed chronologies allowed, and that the start of the New Kingdom has to be pushed down toward younger dates.

The study does not close every open question. It leaves room for debate on how exactly Satdjehuty’s linen should be placed within the court’s burial practices, or how much longer the Second Intermediate Period could be stretched by future discoveries. What it does provide, however, is something that was missing. It offers direct laboratory dates tied to named pharaohs and officials, which can be compared on equal terms to the existing 14C package for Thera.

In a field where, for decades, we tried to align “pottery periods” with “king lists” and struggled to match apples with oranges, this work at least puts the two big narratives, Thera and the New Kingdom, into the same measurement system. Inside the cold chamber of the accelerator, the result is clear. First came the eruption. Then came Ahmose.