Archaeological findings show that a thousand years ago, North America supported bustling urban centers comparable in size and complexity to those in medieval Europe. Yet major questions remain: what forces led these cities to emerge, prosper, and eventually fade away?

A thousand years ago, the land we now call the United States looked very different from what many people imagine. Rather than a sparsely populated wilderness with only small villages, large parts of North America were filled with productive farming regions and major urban centers cities that were just as complex and politically influential as those found in medieval Europe.

This reality has long been hidden because few stone structures survived, which led to a distorted understanding of what the Native Nations of the United States looked like a thousand years ago. But through archaeology, anthropology, and Indigenous oral traditions, a clearer picture is finally coming into focus.

In an interview on the HistoryExtra podcast, historian Kathleen DuVal, author of Native Nations: A Millennium in North America, notes that the centuries around AD 1000 represented “the height of urbanization in Native North America.”

These cities were not isolated curiosities. They served as key centers of politics, trade, and agriculture—networks that connected and influenced communities across the entire continent.

So why had these great cities disappeared by the time Europeans arrived centuries later?

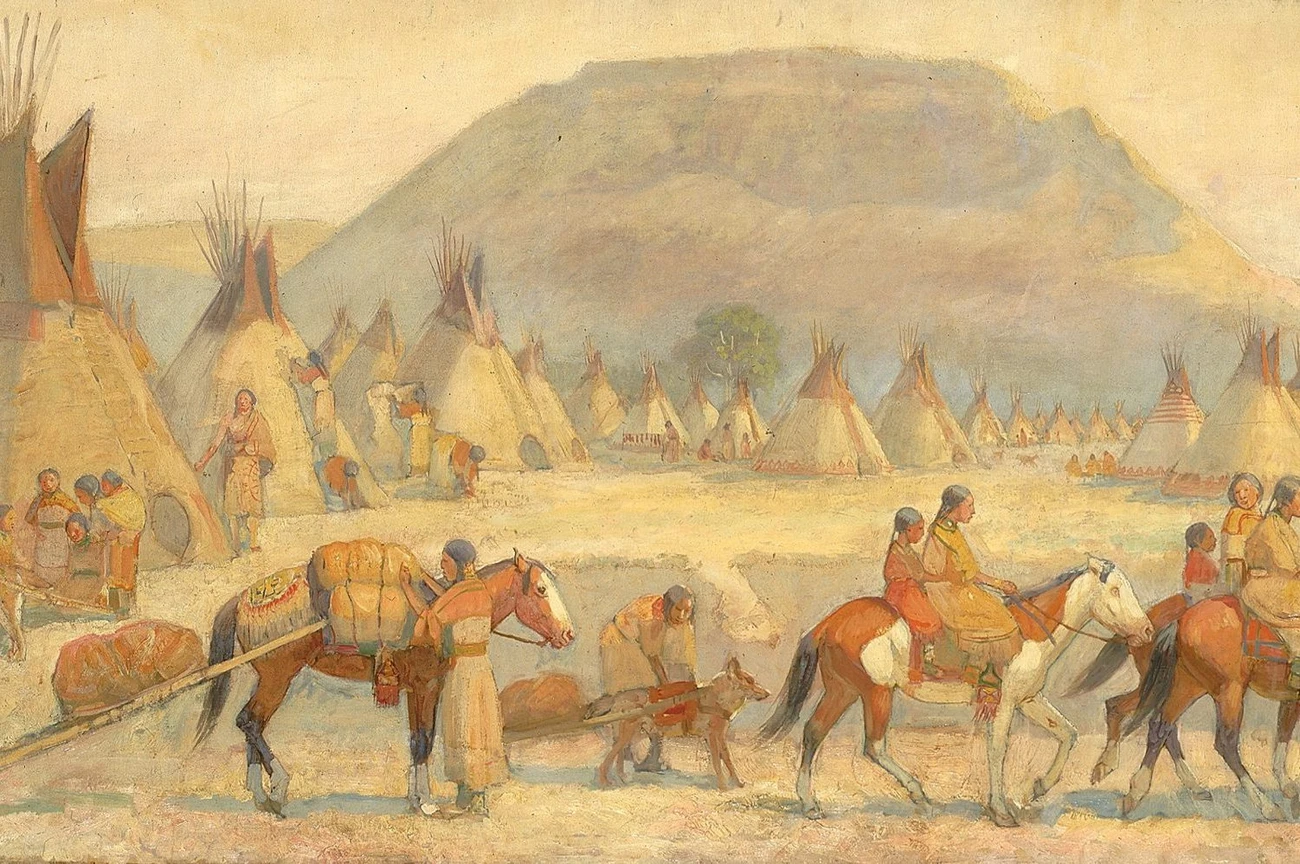

A depiction of the Native North American Blackfoot camp set against the plains landscape. Tipis, riders, and figures at work show the rhythm of daily life within a nomadic community whose culture centred on kinship, mobility, and the great bison herds of the northern plains.

The Urban Landscape of Medieval-Era North America

Across the regions that are now the United States and northern Mexico, large towns and cities served as the centers of regional societies that were, as DuVal notes, “equal in size, complexity, and sophistication to cities in Western Europe.” For context, medieval London around AD 1000 had a population of about 12,000 people.

During this same era, several Native North American cities reached comparable sizes, supported by highly productive farmlands where maize, beans, and squash were cultivated intensively. This agricultural shift—made possible in part by the warmer climate of the Medieval Warm Period from roughly 900 to 1300—created the conditions for rapid urban growth.

According to DuVal, this growth sparked broader transformations, enabling “urbanization, centralization, and the rise of complex economies and powerful religious and political leaders.”

Thanks to food surpluses, these cities became vibrant cultural centers. They supported full-time artisans, religious specialists, and ruling elites, while long-distance trade networks brought copper, shells, obsidian, feathers, and pottery from distant regions.

Cahokia: A Major City at the Heart of the Continent

The largest and most influential of these cities was Cahokia, located in present-day Illinois near the Mississippi River. DuVal calls it “the center of the North American world,” home to “12,000 or so people in its main center […] comparable to places like London.”

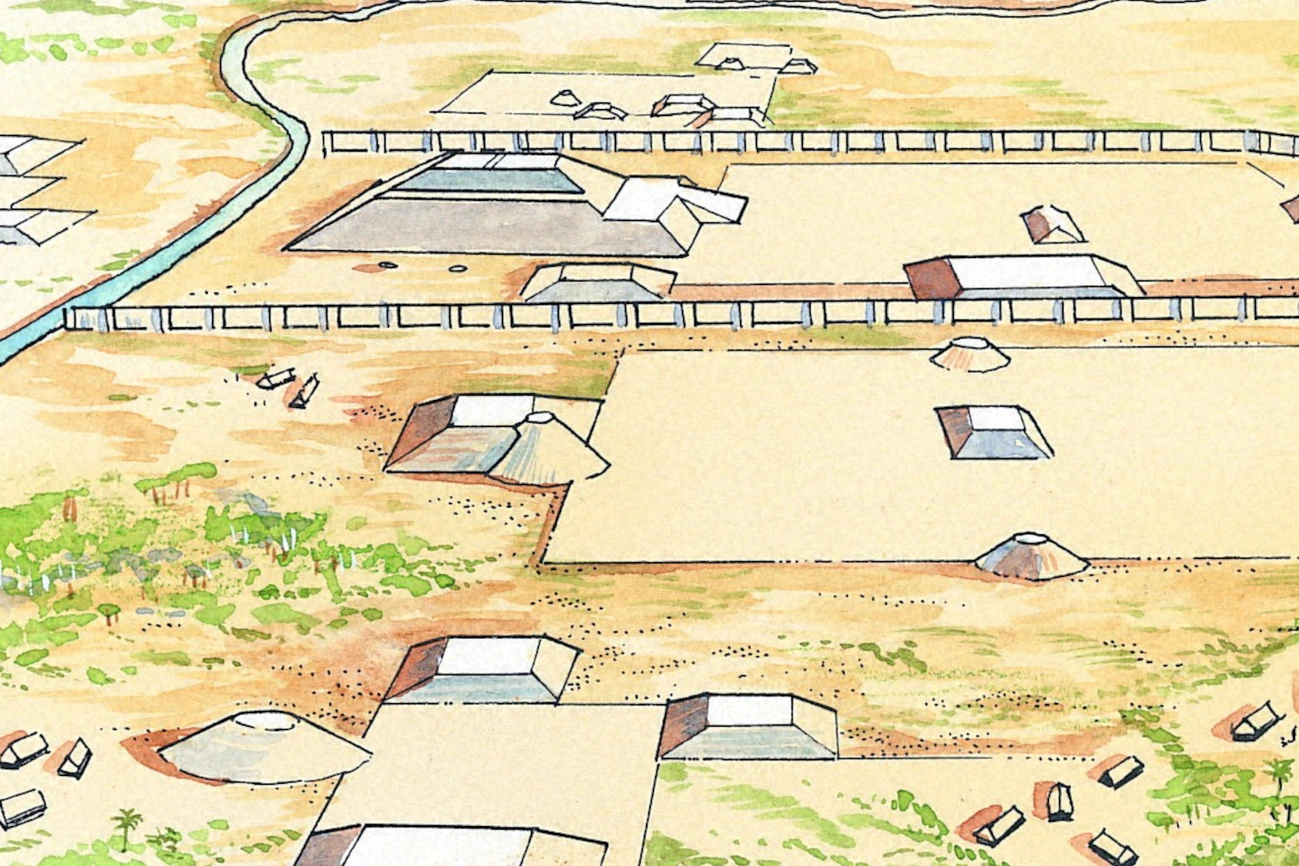

Cahokia was laid out with remarkable planning. Massive earthen mounds formed the bases for temples, elite residences, and civic buildings. The most famous of these, Monks Mound, is still the largest prehistoric earthwork in the Americas. Broad plazas served as spaces for markets, sports, and major ceremonial events.

Beyond the main city, a network of nearby towns and farming villages surrounded Cahokia. These communities were connected through political alliances and economic relationships. Archaeologists have uncovered timber circles used for tracking celestial events, finely crafted shell ornaments, and evidence of large communal feasts—signs of a highly organized and sophisticated society.

Cahokia was not unique. Throughout the Mississippi Valley and the Southeast, mound-building cultures thrived, while in the Southwest, the Ancestral Puebloans constructed multi-story stone settlements such as those in Chaco Canyon. Each region had distinct traditions, yet they shared common traits of urban planning, monumental building, and hierarchical leadership much like the early medieval kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon Britain.

This illustrated reconstruction of Cahokia shows the Native American city when more than a hundred earthen mounds rose around broad ceremonial plazas. At the centre stood Monks Mound — a massive, terraced platform supporting temples and elite residences — surrounded by neighbourhoods of wooden houses, palisades, and bustling marketplaces.

Why these cities changed

Urban life in ancient North America depended heavily on climate and farming, and when environmental conditions shifted in the 1200s, the effects were significant.

As the Little Ice Age began, crops were harder to grow, seasons became shorter, and droughts became more frequent. Communities that had thrived on stable food production suddenly faced shortages. Leaders who drew their authority from promises of abundance found themselves unable to maintain power.

“In some places,” DuVal says, “people turned against leaders who claimed they could control the weather and ensure food, especially during times of famine and drought.”

In other areas, residents simply moved away. By the late 1300s, Cahokia had been mostly abandoned, with its population relocating to smaller, more manageable settlements along rivers and fertile plains. Unlike Europe, where cities tended to endure, many North American societies responded to climate stress by dispersing and reorganizing into flexible, decentralized communities.

This shift was not a downfall but a change in form, and Indigenous cultures across the continent continued to flourish in new social and political structures.

What survives of Cahokia today

The remains of these once-large cities still lie beneath the modern landscape, yet they can be easy to overlook. As DuVal explains, “what you see today in most places are only big earthen mounds […] which now just look like natural hills.”

Because most buildings were made from materials like wood, cane, and thatch—not stone—they did not endure as European structures did. Still, the rediscovered history of these towns shows that North America was once filled with cities, ceremonial sites, and organized nations.

By the time Europeans arrived in the 1500s and 1600s, many of these urban centers had already transitioned or dispersed. Colonists met mobile, village-based groups and wrongly assumed that these societies had always lived that way.

In reality, they were arriving long after centuries of major transformation.