A 40,000-year-old hunting tool is challenging what we thought we knew about Ice Age ingenuity.

An international team of researchers has uncovered compelling new evidence that a mammoth ivory boomerang found in a cave in southern Poland could be the oldest known boomerang ever discovered. Their findings, recently published in PLOS ONE, suggest this sophisticated hunting weapon may date back as far as 42,000 years—making it a remarkable testament to early human innovation in Ice Age Europe.

An Ancient Discovery Revisited

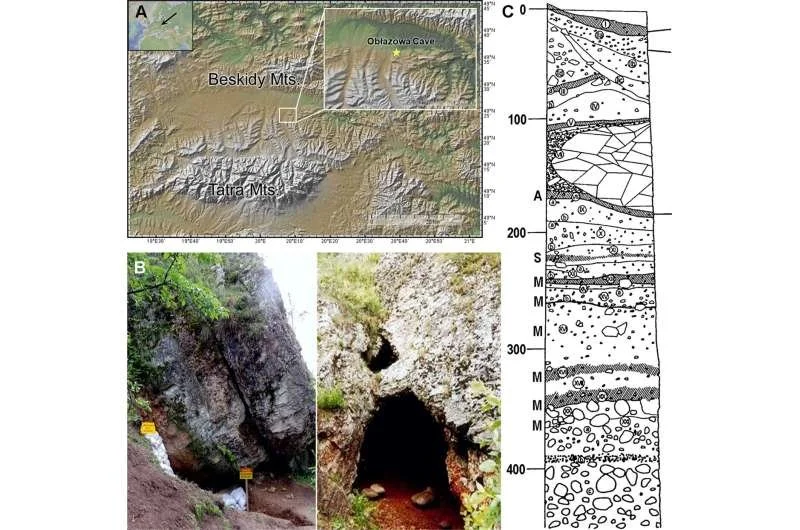

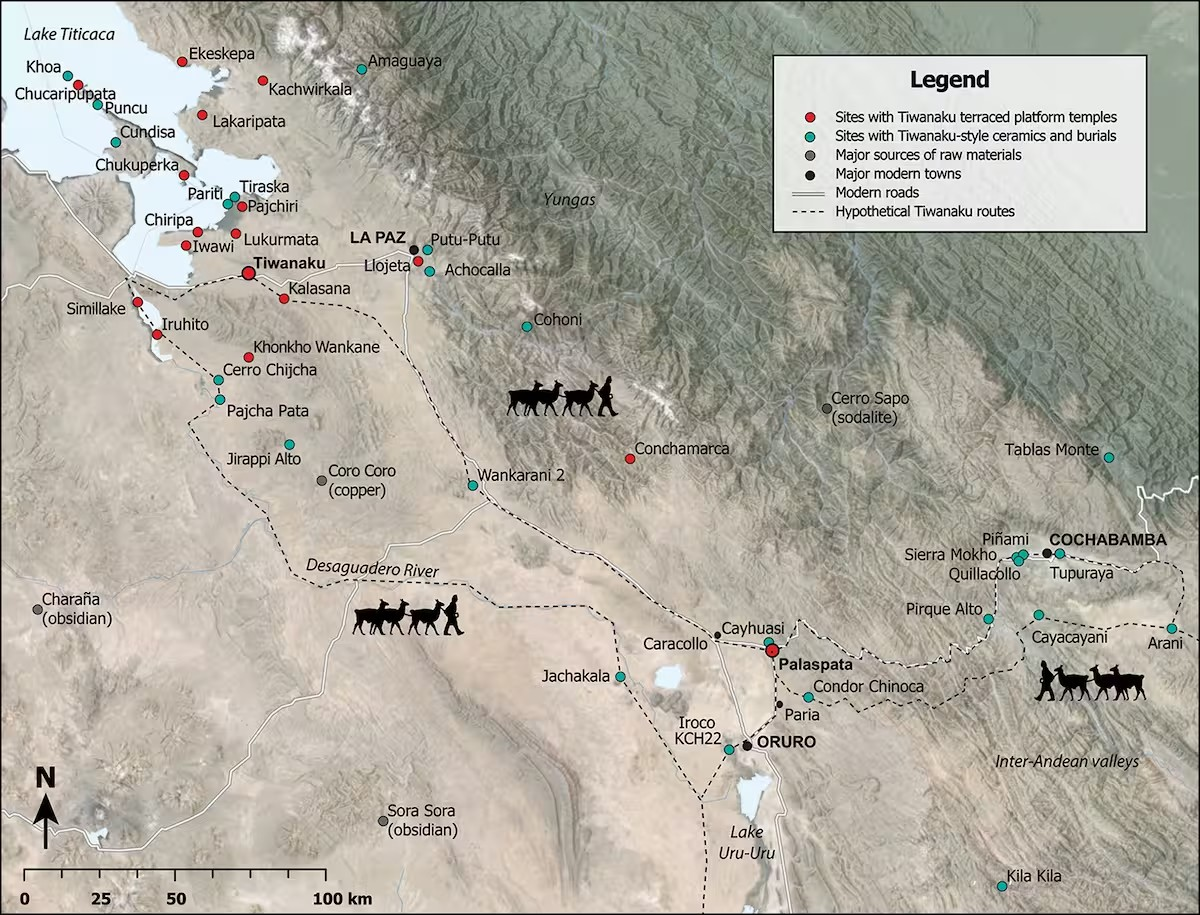

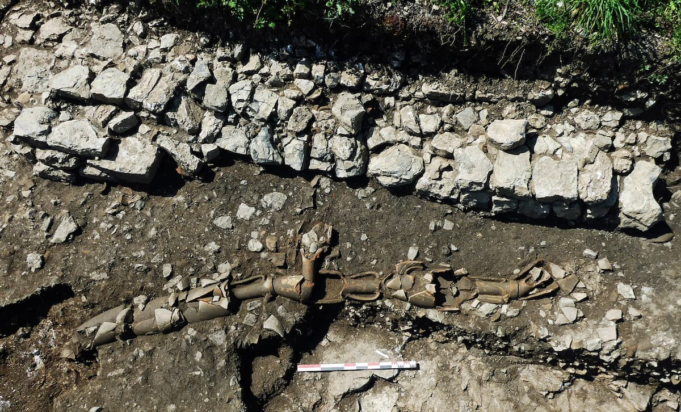

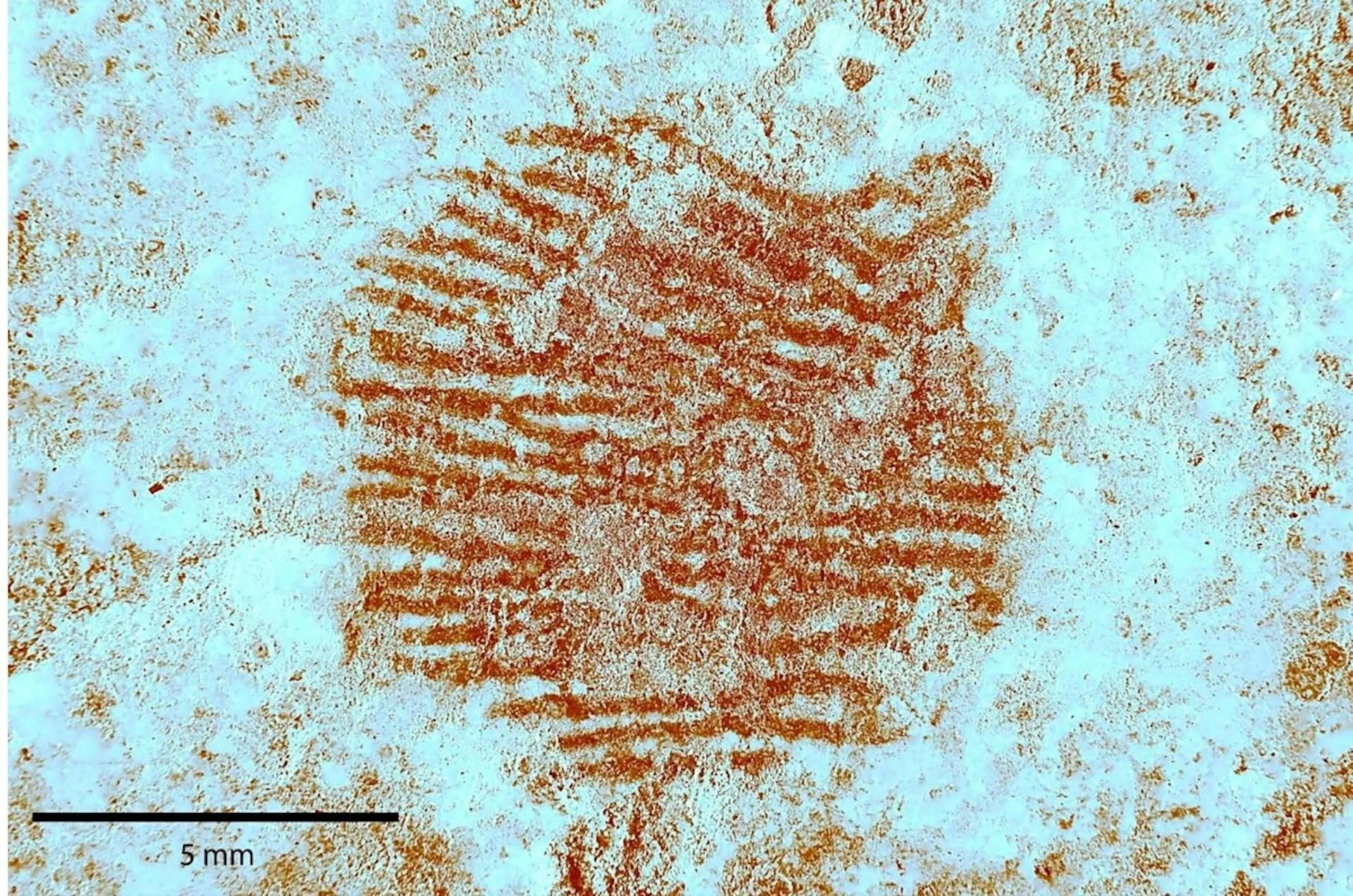

The boomerang was originally unearthed in 1985, deep inside Obłazowa Cave in the Western Carpathians. Measuring 72 cm in length and carved from mammoth tusk, it featured a curved, flattened design nearly identical to the throwing sticks still used by Australian Aboriginal peoples today.

At the time of its discovery, the artifact was recognized as highly unusual—but its true age remained uncertain. An early radiocarbon test gave an estimate of 18,000 years, but this result was later called into question due to contamination from conservation chemicals.

Now, nearly four decades later, the mystery surrounding the boomerang’s origin may finally be solved.

New Clues from Bones, Not the Boomerang

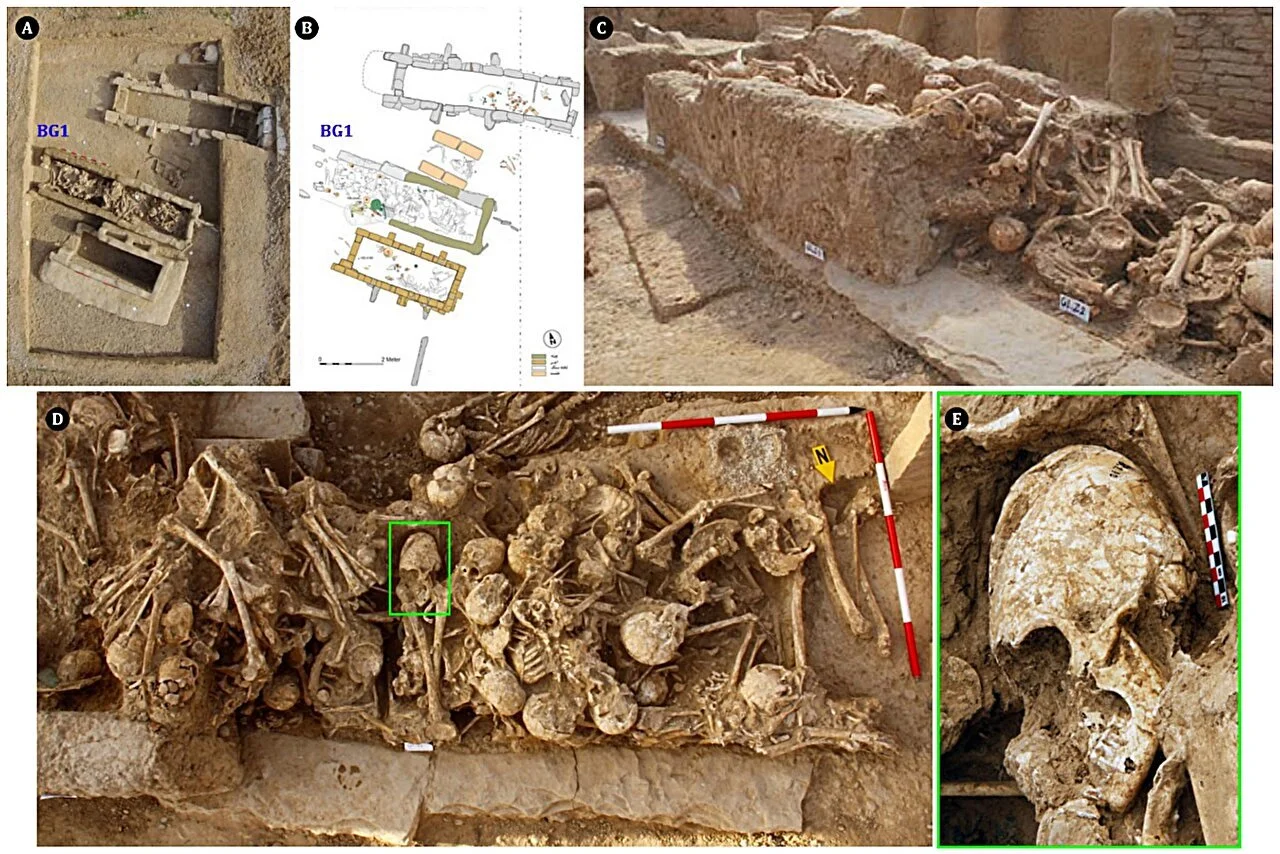

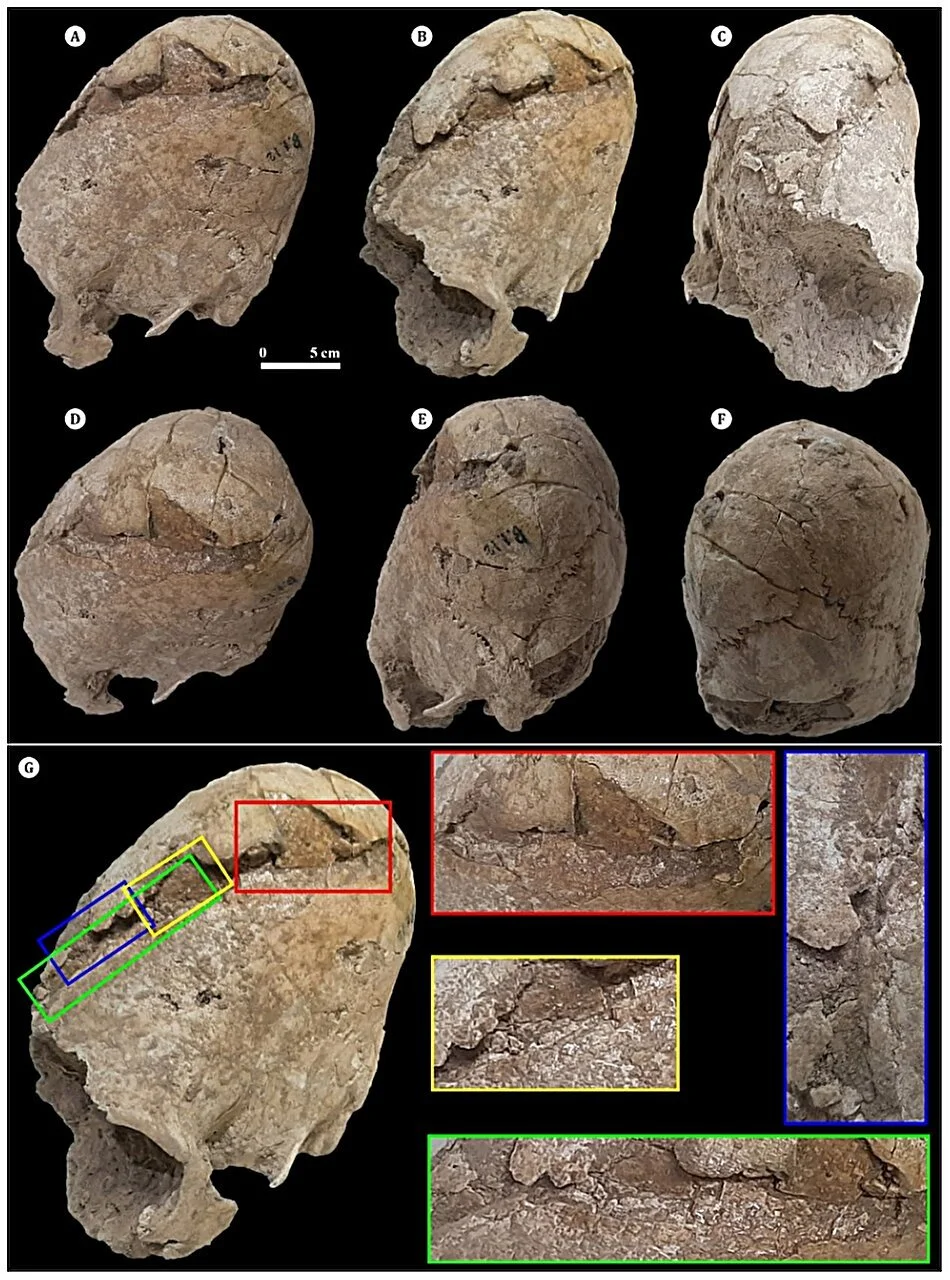

Because the boomerang itself was too fragile to be tested again, the research team turned to indirect dating methods. They analyzed animal bones and a human thumb bone excavated from the same archaeological layer as the boomerang—Layer VIII of Obłazowa Cave.

One standout find: the human finger bone, which was genetically confirmed to be from a Homo sapiens individual who lived approximately 31,000 years ago.

More crucially, radiocarbon dating of numerous animal bones from the same layer—many of them also shaped by human hands—yielded an average age of roughly 41,500 years. Using advanced statistical modeling, the researchers estimate the boomerang dates between 39,280 and 42,290 years ago.

A Weapon Carved from a Mammoth

The boomerang wasn’t just old—it was also made from one of the Ice Age’s most iconic animals. Mammoth ivory, prized for its strength and flexibility, would have required serious skill to carve.

“This wasn’t just a shaped stick,” notes lead researcher Prof. Sahra Talamo. “It was a complex tool that required deep knowledge of materials and aerodynamic design.”

Its arched shape and flattened cross-section are hallmarks of boomerangs designed for straight flight, commonly used to hunt small game or birds—not necessarily to return to the thrower.

A Glimpse Into Prehistoric Intelligence

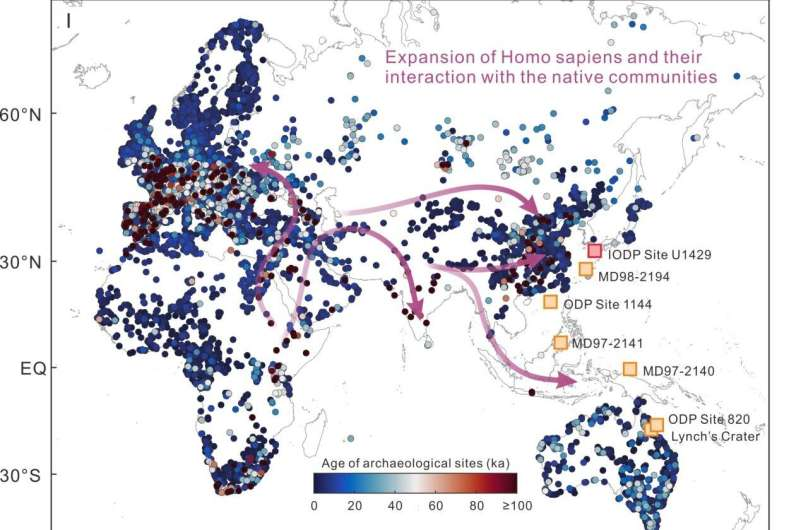

The discovery reshapes our understanding of early humans in Europe. If confirmed, this would push back the timeline for advanced toolmaking in the region by thousands of years, placing Ice Age Europeans on par with their more famous hunter-gatherer cousins in Australia and Africa.

“This find challenges assumptions that such sophisticated weapons were only developed in later, warmer periods,” says co-author Prof. Paweł Valde-Nowak.

Where It Was Found: Obłazowa Cave

Obłazowa Cave, located in Poland’s Podhale Basin, is a rich archaeological site with layers dating to multiple prehistoric cultures, including the Aurignacian, Szeletian, and Mousterian periods. It’s yielded tools, ornaments, and even a rare Paleolithic burial.

Now, it can add the world’s oldest known boomerang to that list.

What’s Next?

While direct testing of the artifact remains impossible, the authors emphasize that more discoveries like this may still be waiting beneath Europe’s soil—or inside museum storage rooms.

“We now have a more refined model for dating such finds,” says Prof. Adam Nadachowski. “And we hope this encourages further reexaminations of Ice Age tools using modern technology.”