The medieval ‘cog’ was nearly 92 feet long and featured castles on its bow and stern.

Archaeologists in Denmark report that a Viking ship discovered near Copenhagen is the largest of its type ever found. Measuring nearly 92 feet in length, the 600-year-old vessel is also among the best-preserved examples of a cog—a “super ship” whose innovative design and cargo capacity revolutionized trade in medieval Europe.

“This discovery is a landmark for maritime archaeology,” said excavation leader Otto Uldum. He noted that the ship provides a “unique chance to study both its construction and daily life aboard the largest trading ships of the Middle Ages.”

Dubbed Svælget 2 after the channel where it was found, the vessel was longer than two school buses and almost as wide as one. Tree-ring analysis of the timber indicates it was built by Viking craftsmen in the Netherlands around 1410 CE. Buried under nearly 40 feet of sand and silt, the ship was shielded from the usual destructive effects of underwater conditions. Svælget 2 is so well-preserved that traces of its original rigging remain intact.

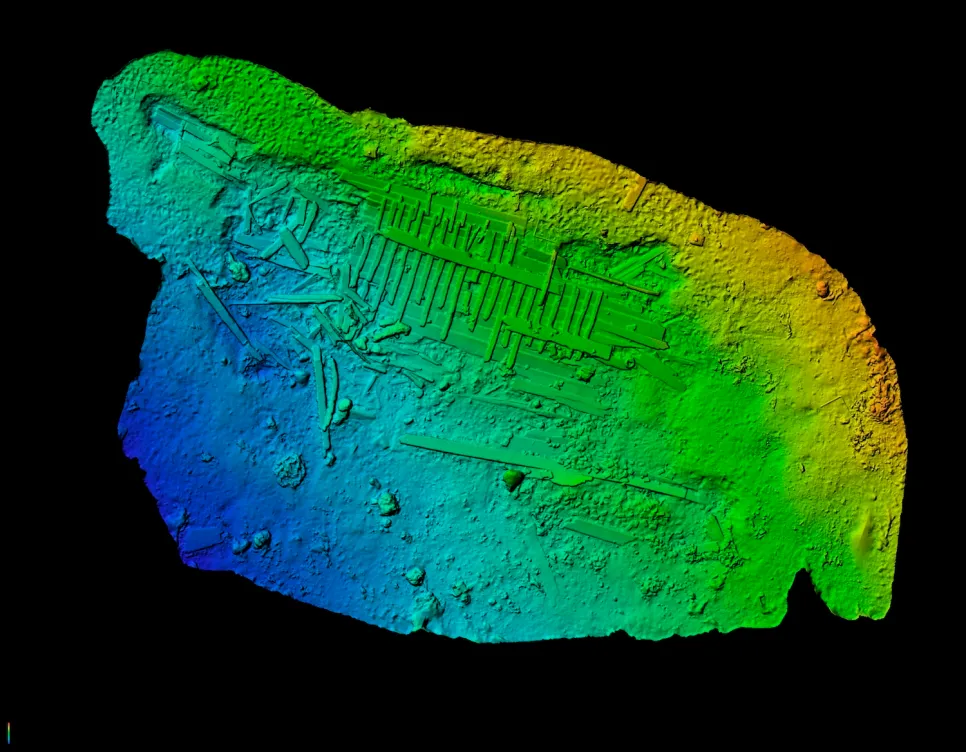

A 3D elevation map showing the remains of Svælget 2.

“It’s remarkable to find so much of the rigging intact. We’ve never seen this before, and it gives us a unique chance to reveal new insights into how cogs were outfitted for sailing,” said Uldum.

Studying Svælget 2’s rigging will allow archaeologists to understand how a relatively small crew managed such a large vessel on its many journeys.

“The discovery shows how complex challenges like rigging were handled on the largest cogs,” Uldum explained. “Rigging is crucial on a medieval ship—it allows control of the sails, secures the mast, and protects the cargo. Without it, the ship would be useless.”

The researchers also confirmed that some Viking cogs included tall wooden structures at the bow and stern, known as castles. While historical drawings had long depicted these features, no archaeological evidence had ever verified them—until now.

“We have plenty of illustrations of castles, but they’ve never been found because usually only the lower part of the ship survives,” said Uldum. “This discovery finally gives us archaeological proof.”

Despite its size, the cog required a relatively small crew to pilot.

At the stern castle, archaeologists uncovered a covered deck that offered the crew shelter and protection. Compared to other shipwrecks, Svælget 2 provides roughly 20 times more material for study.

“It’s not comfort by modern standards, but it’s a significant improvement over typical Viking Age ships, which had only open decks in all kinds of weather,” Uldum noted.

While the find doesn’t change our basic understanding of medieval maritime trade, Svælget 2 demonstrates the immense investment, resources, and technical expertise required to build such a vessel.

“We now know, beyond doubt, that cogs could reach this size—that this ship type could be expanded to such extremes,” Uldum said.